Issue:

July 2024

A Hibiya Line tour of law and order, Edo-style

For many years, when the FCCJ was located on the 20th floor of the Yurakucho Denki Building, a cluster of old two-story buildings could be seen directly below the window on the east side of the main bar.

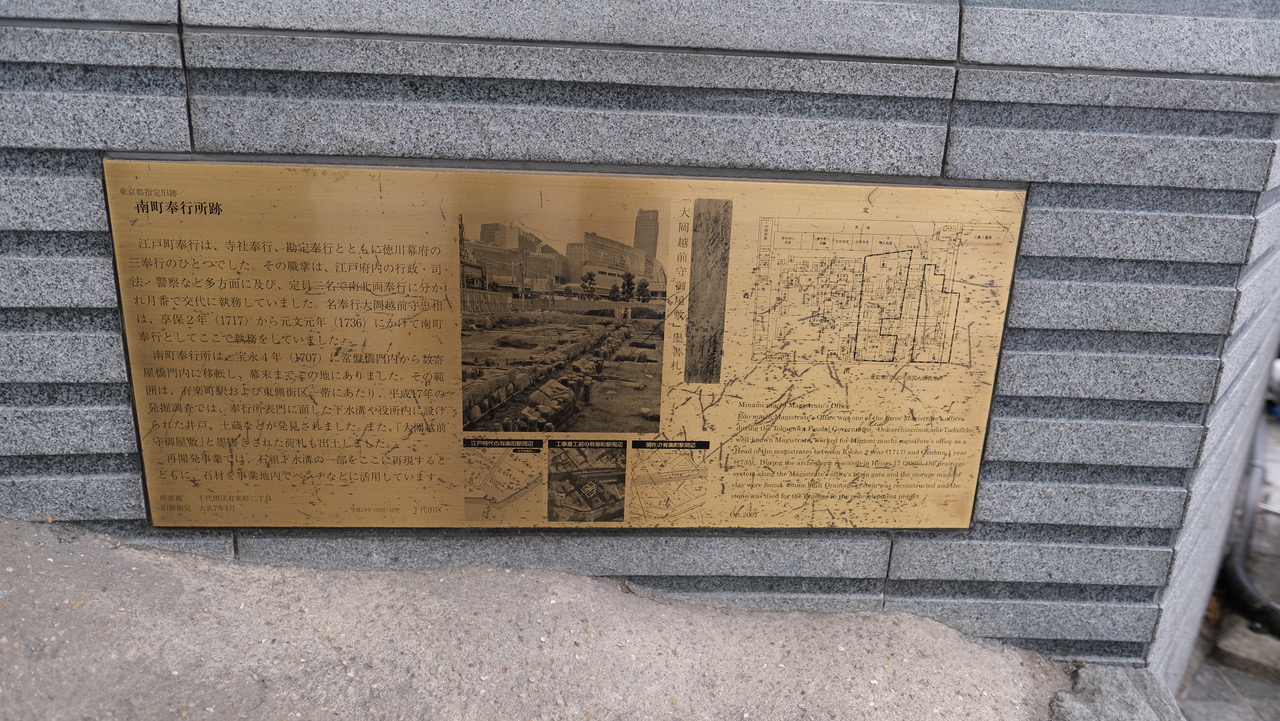

This space, cleared and renovated some years ago, had been situated outside the old Sukiyabashi gate. It was formerly occupied by the city’s Minami Bugyosho (south court), where one of Edo's two magistrates, or governors, dispensed justice. Its counterpart was the Kita Bugyosho (north court), located close to the Yaesu north exit of Tokyo central station.

In addition to trying and ruling on criminal cases, the machi bugyo (commissioner or governor) was responsible for tax collection, supervising the fire department and other functions of the city.

Today, all that remains of the court in Yurakucho is a row of stones and a small brass plaque, directly across the street from Kotsu Kaikan.

If you board the Tokyo Metro's Hibiya line downstairs, you can give yourself a full tour of the city's main landmarks related to law and order back in the time when Tokyo was still Edo.

From Hibiya it is five stops to Hatchobori. There's not much point in getting off the train as nothing of note remains to indicate its status in olden times, except an explanatory signboard in Japanese close to JR Hatchobori station.

This neighborhood, however, once figured heavily in the scheme of law enforcement as it was where Edo's police officials – called yoriki (police sergeants) and doshin (constables) – lived with their families. It was conveniently located to enable the city's lawmen to commute between the two courts and the jail at Kodenmacho.

In the parlance of Edo's commoners, police officials were referred to as Hatchobori no danna (masters of Hatchobori).

Hatchobori's name comes from the length of the adjacent canal, which was dug in 1612. When excavated it came to eight cho, or city blocks. (A cho was equivalent to roughly 109 meters.)

Yoriki were paid an annual stipend of 200 koku (one koku was considered enough rice to feed one person for a year), one horse, one spear, and a house of about 300 to 500 tsubo (991 to 1668 square meters), while doshin received 30 koku of rice and lived on a lot of about 100 tsubo (332 square meters).

Alas, no vestiges of this community remain, but there is plenty to see at Kodenmacho, three more stops along the line. Just one minute from the main intersection is the site of Denma Rogoku, at one time Japan's largest jail. The area is now called Jisshi Park, whose dimensions correspond to roughly 80% of the 8,637 square meters (2,618 tsubo) of the jail in its heyday. It closed in 1875, when a new prison was completed in Ichigaya.

A scale model of the jail buildings can be viewed here.

Pre-modern Japan did not have prisons in the modern sense, where a person convicted of a crime was sentenced to specific period of incarceration. The jail was more of a detention center where the accused awaited their sentences, which included execution, tattooing, expulsion from Edo or exile to the Izu islands.

About 38 people were employed by the jail, overseen a middle-ranked samurai who took the hereditary name Ishide Tatewaki. Male and female prisoners were held separately, and strict class distinctions were maintained among prisoners, with better conditions for samurai, doctors and others with high social status. Prisoners rose at 4 a.m. and bedded down at 8 p.m. Aside from the roll call and the two simple meals, served at around 8 a.m. and 5 p.m., there was little else to keep them occupied. Prisoners bathed three times a month in winter, four times a month in the spring and autumn, and six times a month during the summer.

Prisoners could not receive visitors, but could be gifted with certain provisions, such as strips of dried fish, to supplement the jail's meager diet. For a price, sake and tobacco could be smuggled in. In exchange for added rations, a prisoner could volunteer to stay up all night to shoo rats away from the others while they slept. On hot days, the lowest prisoners in the pecking order were coerced into taking turns fanning the head trusty – a prisoner who is given special privileges or responsibilities in return for good behavior.

The jail had a capacity of around 400. When at its most crowded, conditions in the commoners’ jail were appalling, with prisoners packed together like sardines. By one account, 18 men were forced to spend the night atop a single tatami mat. This was done by making them kneel upright, in two rows of nine facing each other. Knees were fitted between those of the person sitting opposite. Each neighbor’s shoulder was used as a pillow.

Severe overcrowding and contagious diseases contributed to high prisoner mortality, and the intolerable conditions occassionally led to murder.

Out of a total of 8,604 prisoners incarcerated during the years 1818-20, for example, 620 died. This particularly high rate – about 7.2% - resulted from poor rations during a period of food shortages.

When fires broke out, the jail operated on an honor system. Just after the Lunar New Year in 1841, during a major conflagration, prisoners were released with orders to “return within three days”. History records that they did, with no exceptions. Between the 1650s to the 1860s, similar events are said to have occurred over a dozen times.

Jisshi Park near Kodenmacho corresponds roughly to the Denma Rogoku, Edo's jail until 1875.

Just across the street from Jisshi Park is a Kubikiri (head-chop) Jizo statue, now on the grounds of the Daianraku-ji, a temple of the Koyasan Shingon sect. The jizo is situated at what was the jail's southeast corner where executions, in the form of decapitation by sword, were performed.

After passing Akihabara and Ueno we arrive at Minowa, the closest station to the Shin-Yoshiwara brothel quarter, and the Jokan-ji temple, famous for its muenbotoke, an unmarked grave for thousands of prostitutes. But let's save these for a future article.

We reach Minami Senju, the final station on our tour. Descend the steps at rear of the train, cross the street, and you'll find yourself at Kotsukappara, one of Edo's three main execution grounds. The area is now the location of the Enmeiji and Ekoin temples and their cemeteries. The grounds were situated astride Oshu Kaido, the road leading to Tohoku. Like the Suzugamori execution ground on the Tokaido near Omori and the Itabashi execution ground on the Nakasendo, it was intended to warn arrivals to Edo that stern punishments awaited lawbreakers.

Most of Kotsukappara's grounds are now buried under railroad tracks, but in its heyday, it was about the size of a soccer pitch.

The Enmeiji, with its 3.6-meter high Kubikiri Jizo, is the more photogenic. This guardian diety, erected in 1741, was moved to its present location in 1895 to make way for railroad construction. A large engraved stone in the foreground bears the cursive characters, "Namu myoho renge kyo," (Hail, Book of Lotus of the Good Law), the prayer of the Nichiren sect. These served as the only solace available to the condemned, since Japan did not introduce prison chaplains until 1872.

At the entrance to the neighboring Ekoin can be found the Yoshinobu Jizo, a memorial to 4-year-old Yoshinobu Murakoshi, who on March 31, 1963, was kidnapped for ransom and murdered by a 29-year-old ex-convict, Tamotsu Kohara.

The Yoshinobu-chan jiken made national headlines and would become known as the first case in Japan where language experts were mobilized to identify a suspect. This was done by listening to a recording of Kohara's telephoned ransom demand to the boy's family and tracing his accent to Fukushima Prefecture. (Kohara was convicted and hanged in December 1971).

It was at the Ekoin that in 1774 a team of physicians led by Sugita Gempaku observed the dissection of the body of a woman known as Aocha Baba (Green Tea Hag), who had been executed by decapitation. Sugita referred to a Dutch anatomical text, Ontleedkundige Tafelen, and over three years would painstakingly oversee its translation into Japanese. His book, called the Kaitai Shinsho, marked a key step toward the study of western medical science in Japan.

In 1873, 970 executions were performed at Kotsukappara, which works out to an average of 2.65 per day. An account by a western journalist appeared in the Times of London. The article appears to have been written by Anglo-Irish journalist Francis Brinkley (1841-1912), who later went on to found the Japan Mail, one of the forerunners of the Japan Times.

In a post on 16 October 1873, the writer begins by explaining he had gone to observe the executions out of “vile curiosity”.

He wrote: “I repented of it, but still it was a most extraordinary spectacle, and impressed me very much.

“The culprits were eight in number, one being a woman. They were all beheaded with a sword. The operation was performed with wonderful dexterity and coolness, and not one of them, even the woman, showed the slightest symptom of fear.

“On one side of the enclosure were two Japanese officials, in chairs, to see the thing properly conducted. The criminals were placed in a row, on one side of the enclosure, blindfolded with pieces of paper. What struck me most was the horrid coolness of the executioner’s assistant, a good-looking lad of 18; he went up to each poor wretch in his turn, gave him a tap on the shoulder, led him up to the mound, and made him kneel on the mat; he then stripped his shoulders, made him stretch out his neck, said 'That will do,' and in a flash the man’s head was in the hole in front of him and his bleeding neck was, as it were, staring me in the face. The assistant, still with the same pleasant smile, picked the head up, threw some water on the face to wash off the blood and mud, and presented it to the Japanese officials, who noted and signed to go on with the next; the assistant then gave the corpse a blow between the shoulders to expel the blood, and finally threw the carcase [sic] aside like a log of wood. He then repeated the same pleasant programme with the next.

“I never thought a man’s head could come off so easily; it was like chopping cabbages, only accompanied with a peculiar and most horrid sound – that of cutting meat, in fact.

“There was a dense crowd of Japanese present, including many women and even children; these people never ceased to eat, smoke, and chatter the whole time, making remarks on the performance, and even occasionally laughing, just as if they were at a theatre. The executioner poured water on his sword between each decapitation, as one wets a knife in order to cut India rubber.”

Mark Schreiber is author of Shocking Crimes of Postwar Japan (Yenbooks 1996) and The Dark Side: Infamous Japanese Crimes and Criminals (Kodansha International 2001).