Issue:

October 2022

Abe’s state funeral sends the wrong message, anti-cult lawyer tells FCCJ event

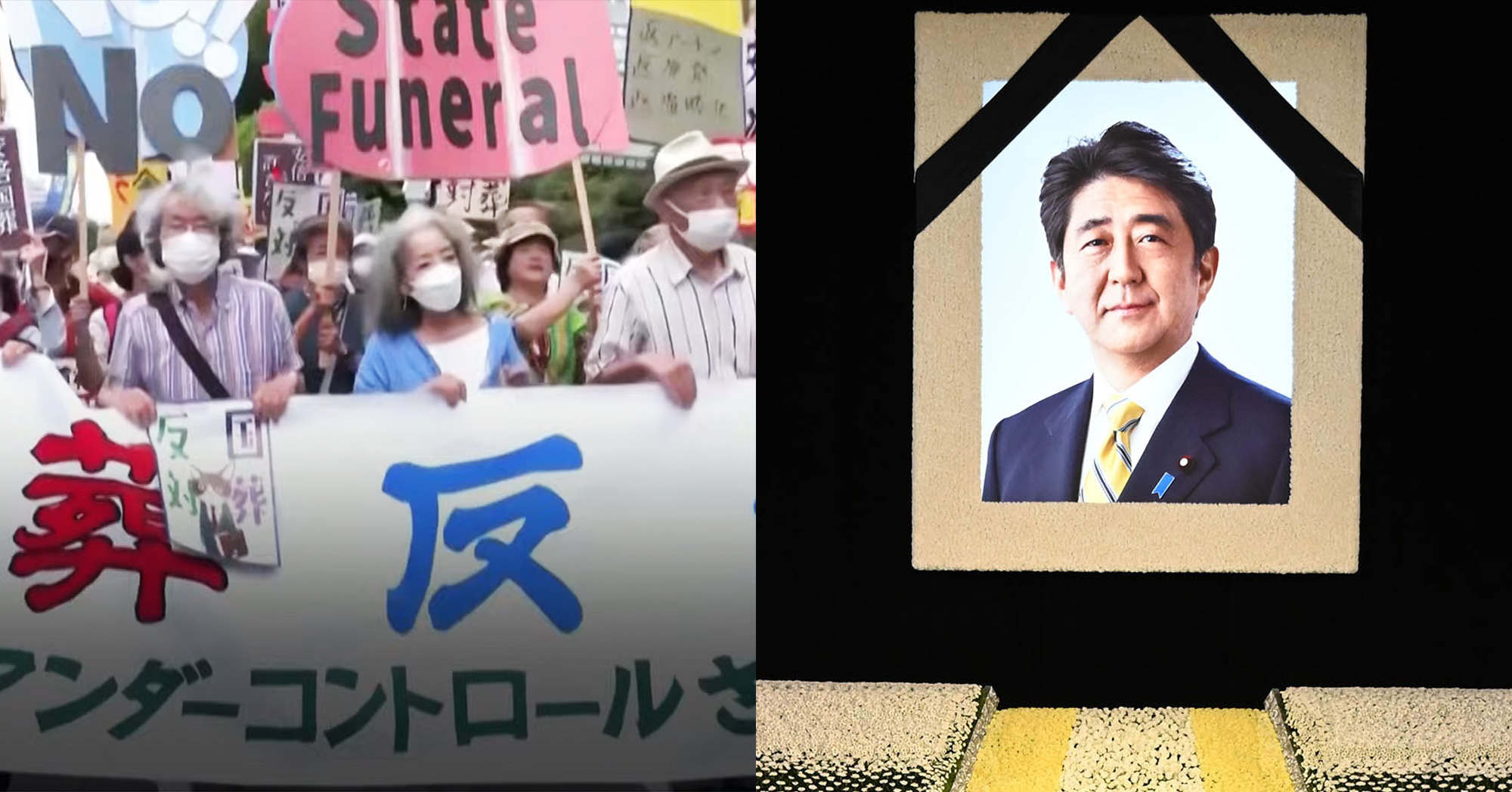

Former prime minister Shinzo Abe received his send-off in front of 4,300 people, including foreign dignitaries, at the Nippon Budokan last month. The ceremony went ahead despite deep divisions on Japanese society. While thousands queued to lay flowers and pray at a specially set up site near the venue, many others demonstrated in the streets. And opinion polls showed that a majority of voters opposed granting a state funeral for the country’s influential former leader.

For months, groups of citizens had protested in front of the Diet building and other locations in Tokyo and elsewhere. On September 21, a man set himself alight near the Prime Minister’s Office in an apparent protest. The day before the funeral, thousands of protestors marched through the streets of Tokyo and, a day later, gathered near the Nippon Budokan as the ceremony was taking place.

People overseas, and a number of foreign correspondents based in Japan, appear to have been taken aback by the protests and the level of organized resistance to an event that was intended to pay tribute to one of Japan’s most influential postwar politicians.

How did honouring Japan’s longest-serving prime minister generate such intense controversy?

Abe's divisive legacy stretches back well before he was assassinated on July 8 while making an election campaign speech in Nara. The alleged killer, Tetsuya Yamagami, said he had targeted Abe because of his ties to the controversial Unification church, which he blamed for bankrupting his family.

Some critics argued that Abe did not deserve a state funeral because he was a politician, not a monarch.

Rules governing state funerals are set out in the constitution, according to Masaki Ina, an advisor at the Peace Research Institute at the International Christian University. He told an event at the FCCJ on September 14 that prior to Abe, only one other postwar prime minister, Shigeru Yoshida, had been afforded the honour, in 1967.

Protesters believe that holding a state funeral was tantamount to glorifying Abe’s legacy and ignoring his many failures, not to mention his implication in several major scandals.

Like his grandfather and former prime minister Nobusuke Kishi, Abe was determined to end Japan’s postwar security arrangements – encapsulated in the “pacifist” Article 9 of its US-authored constitution, and give the country’s military a more robust role.

Abe’s enthusiasm for constitutional reform was one reason why dozens of organizations opposed his state funeral. They regard his re-interpretation of the meaning of the constitution, which culminated in a 2016 law permitting Japan to engage in collective self-defence, as a betrayal of democracy. Other critics of the state venue were motivated by opposition to Abe’s conservative stance on issues such as same-sex marriage and allowing married couples to retain separate surnames.

Then there were the scandals, most notably his alleged involvement in the sale of public land at a heavily discounted price to the ultra-nationalist operator of Moritomo Gakuen, a private kindergarten in Osaka. Abe denied any involvement.

But it was Abe’s involvement in the Unification Church that arguably fuelled the torrent of criticism of his funeral arrangements. Kishi was instrumental in helping the church establish a base in Japan after it was founded in South Korea in 1954 by the self-proclaimed messiah, Sun Myung Moon. Today, some analysts claim that 80% of the church’s revenue comes from Japan.

The church shared Abe conservative stance on history, security, and social issues, as it clung to its founding principle of securing “victory over communism”.

Ties between the church and members of the governing Liberal Democratic Party have been an open secret among those who take an interest in Japanese politics, but media revelations about the relationship in the wake of Abe’s death have sparked genuine anger and surprise among many voters.

A survey commission by the current prime minister, Fumio Kishida, revealed that nearly half of the party’s lawmakers had in some way associated with the church, some of whose members had campaigned for LDP candidates.

Masaki Gouro, a member of the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales – which defends victims of the church’s aggressive fund-raising methods - warned that the movement had shown signs of revering Abe as a martyr. Giving Abe a state funeral would send the wrong message to people who have fallen under the influence of the church, he said at the FCCJ event.

Ilgın Yorulmaz is a freelance reporter for BBC World Turkish. She is the Second Vice President of FCCJ.