Issue:

Letter from Hokkaido | November 2022

Russia and North Korea have propelled Hokkaido into heart of Japan’s defence debate

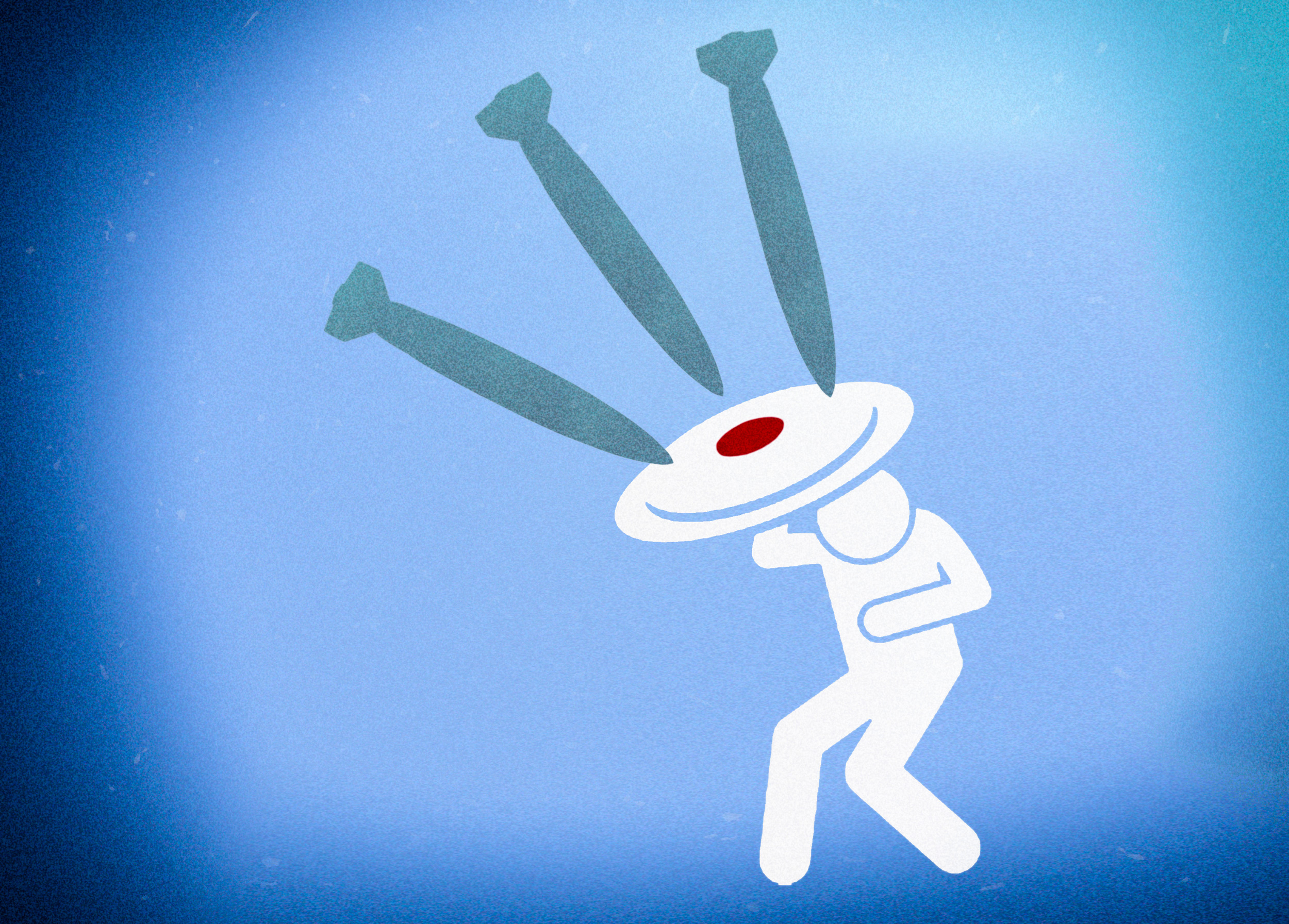

Here we go again. That was the feeling in Hokkaido when North Korea launched a missile that flew over Japan’s northern reaches in October and traveled about 4,600 km before landing in the Pacific Ocean. It was the first time in five years that Pyongyang had sent a missile over Japanese territory.

The launch created a media frenzy in Tokyo and drew the usual condemnations from the Japanese government. Here in Hokkaido, some early morning trains and subways were halted for a few minutes after warning of the launch arrived. But Sapporo’s residents kept calm and carried on, far less worried about North Korean missiles falling on their heads than missing their early-morning appointments due to the train stoppage.

It's not that we don’t take the risk of North Korean missiles lightly in Hokkaido. We certainly do. But due to geography and demographics, Hokkaido faces more complicated questions about its defense than simply how to guard against North Korean missile launches. Questions that Japan’s Tokyo-based politicians tend to ignore when security debates become focused on North Korea, China’s actions around the Senkaku Islands, or what Japan should do to help keep the peace in the Taiwan Straits. Only when a missile launch in the general vicinity of Hokkaido occurs do we see a flurry of articles and commentary in the national media about the need to strengthen the security of Japan’s northernmost main island.

Historically and today, Russia, rather than China or North Korea, has been viewed with most suspicion by people in Hokkaido. Any debate about beefing up Hokkaido’s (and Japan’s) security in this part the country starts with Russia in mind. The most basic questions I hear begin with: are there enough Hokkaido-based Ground Self Defense Forces, especially in eastern and northern Hokkaido, in order to repel a Russian attack or invasion?

In 1979, there were 50,000 GSDF forces in Hokkaido. The end of the Cold War led to a drawdown. By this year, there were only 37,000 troops. Two of the closest bases to Russia are a small GSDF base at Shibetsu, on Hokkaido’s eastern coast, facing Russian-held Kunashiri, and a small Maritime Self-Defense Force outpost on the northern tip of Wakkanai, almost within sight of Sakhalin. The Air Self-Defense Forces has a large base at Chitose airport near Sapporo and stations on Hokkaido’s remote eastern and northern coasts.

Unlike the more densely populated central and western parts of the prefecture, Hokkaido’s eastern half is remote, rural and declining in population. This is well known among one group in particular: Chinese investors. Stories of China-backed money purchasing prime areas of Hokkaido land for resort development are old news locally, but have finally led Tokyo to ask the question of whether it’s really a good idea for security-sensitive installations such as military bases and nuclear power plants find out the new next-door neighbors are from countries that are, at the very least, strategic competitors?

In October, the Japanese moved to more heavily regulate land sales in areas of the country it deems sensitive. For Hokkaido, that means those purchasing land in seven areas, including near a small Air Self-Defense Force base in Nemuro, will face background checks and restrictions on the size and design of what they can build.

For existing SDF bases in Hokkaido, another question faced by the defense budget increase debate is whether to upgrade and expand them or close and consolidate them.

Many smaller facilities date back to the Cold War era and are in need of repair and modernization. If the plan for Japan’s increased defense spending means building or buying more missile batteries, anti-missile defense systems, and building up its drone fleet on new bases in sparsely populated areas, the next question is whether to figure out where on Hokkaido to locate these next-generation technologies and then invest the money needed to put them in new locations. The alternative is to deploy them at an existing SDF base - a cheaper alternative that may not be as strategically sound given present realities.

Within the larger debate over a proposed defense spending increase is also the question of who gets the money and why. For example, is having a stronger Coast Guard, which comes under the auspices of the Ministry of Land, Transport, and Infrastructure, really necessary?

Not surprisingly, ministry bureaucrats think so. Upgrading the Coast Guard and building up the related local port infrastructure by claiming the need to do so for “security” reasons is good old-fashioned pork-barrel politics. But the winners who get their share of the spending pie are likely ports in electoral districts controlled by elderly, influential Liberal Democratic Party members.

The Coast Guard, of course, has facilities in Hokkaido. But there are not that many powerful LDP veterans here to do the requisite arm-twisting in Tokyo to get port-related funding under the pretext of strengthening national defense. Certainly not out east, where the once feared Muneo Suzuki is still around, but not nearly as powerful as he once was.

Whether Hokkaido ultimately gets its share of any national “defense” spending thanks to powerful Diet members, regardless of whether such spending is actually consummate with Japan’s real strategic defense needs, also remains to be seen.

Eric Johnston is the Senior National Correspondent for The Japan Times. The views expressed within are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of The Japan Times.