Issue:

An excerpt from Japan’s Prisoners of Conscience: Protest and Law During the Iraq War by Lawrence Repeta (Routledge, 2023)

The administration of George Bush demanded Japanese boots on the ground to support its 2003 invasion of Iraq. Eager to loosen the shackles of article 9 of the constitution, the then prime minister, Junichiro Koizumi, responded by deploying a small contingent of the Self-Defense Forces [SDF].

The first significant SDF contingent left for Iraq on January 16, 2004. The following day, three members of a tiny antiwar group known as the Tachikawa Tent Village walked the corridors of SDF apartment buildings in western Tokyo with flyers titled “Let’s Think Together and Raise Our Voices Against the SDF Deployment to Iraq!” They were arrested a month later and charged with criminal trespass. They would be detained in police cells for 75 days.

The Tent Village had continuously protested against war and the Self-Defense Forces since it was formed in 1972, when the government announced that the SDF would replace U.S. military forces departing Tachikawa. The sudden arrests shocked the Tent Village community and antiwar groups throughout Japan.

The case presented a severe test for Japan’s judiciary, charged with upholding the right to free political speech against such an aggressive police crackdown. This book tells the story of the arrests and trial and of the lawyers, constitutional scholars, and others who supported the protesters.

Trial of the Tent Village Three

Fifth public court session, September 9, 2004

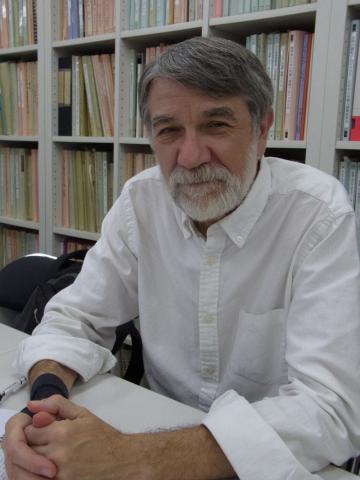

The first defense witness was Yasuhiro Okudaira, Japan’s most celebrated expert on the right to freedom of speech. Okudaira was born in Hakodate on the northern island of Hokkaido in 1929 and entered the University of Tokyo as a freshman in 1950. He was in the first wave of Japanese scholars to begin their studies under Japan’s postwar constitution. As a student and then a young scholar in the 1950s, he grappled with the fundamentals of the 1947 “Peace Constitution” that accomplished a revolution, replacing a legal system based on the will of a divine monarch with a radically different system founded on popular sovereignty.

Dissatisfied with senior scholars’ efforts to reconcile lifetimes of study under the old system with Japan’s new constitutional democracy, he applied to study in the United States. In the 1950s, Japan was fighting its way out of the poverty left by the devastation of the war years; opportunities to study abroad were scarce. Among other challenges, access to foreign currency was limited. But Okudaira’s application was accepted and he began studies at the University of Pennsylvania Law School in the fall of 1959, the first Japanese to study there after the war 1. He returned to Japan two years later, and in the decades to follow compiled a record of research and writing that earned him the exalted status of one of Japan’s most prolific and respected constitutional scholars. 2

There is no doubt that Okudaira held deep sympathy for the plight of the Tent Village defendants and others in the antiwar movement. This sympathy was rooted in his own commitment to peace and his fear of unlimited government power 3. He was one of nine public intellectuals who had founded the Article Nine Association just three months earlier. Like others of his generation, Okudaira’s gruesome war memories were deeply imprinted. He recalled his student days in a memoir:

"There was one problem that never left my mind. With a single slip of red paper, the state could draft people into military service and send them off to war. Their death in battle would be a source of glory. What was this 'state'? What was the source of its power? When I was a child, men that I knew were taken away with a single slip of red paper. And I saw that when they died in battle, only their bones returned home. Yes, the state held immense power." 4

He was driven to study the Constitution because “constitutions were made to restrain this power. Little by little, I learned that something called fundamental human rights served to restrain the state”.

Attorney Shizu Yamamoto, the most junior member of the five-lawyer defense team, conducted Okudaira’s examination. She began by posing a series of basic questions about constitutional protection for free speech. The old scholar patiently responded with answers that had become orthodoxy in Japan in the early 21st century. Notes from courtroom spectators do not record the reactions of the three judges, but one suspects that they nodded off from time to time during this stretch of the testimony. The witness was simply reciting generalities that could be found in any textbook on constitutional law in Japan.

Then Yamamoto changed direction, asking whether the arrests followed by detentions as long as 75 days and prosecutions “might have effect on the right to free speech, not only on the defendants, but on the people in general?”

“I think so,” Okudaira responded, “because, you see, trespass is a prime example of a matter for the general criminal law. If applying such general laws to cases like this becomes routine, it means not only that punishing such acts becomes routine, but also that police action, with interrogations and then indictments, with very broad investigations, or as you point out, extremely long detentions, could follow”.

Regarding the political effect of such a regime, he said: “If the law is managed in a way with a very strong political coloration … it would not only be the detention of certain people, it would have a huge effect on others around them ….” 5

If this became the new normal in Japan, Okudaira feared that such aggressive application of criminal law would not be limited to allegations of trespass. “All kinds of matters could lead to crackdowns and arrests,” he said. “There could be arrests followed by investigations that cast a broad net around suspects. In other words, forgive me for expanding the scope of the discussion, but I have done much study of the Peace Preservation Law. This would be just like cases prosecuted under the Peace Preservation Law in the prewar period.”

The dreaded words “Peace Preservation Law” sent a shockwave through the courtroom. First adopted in 1925 and later revised to mandate even stricter measures, including the death penalty, the law made it a crime to hold beliefs incompatible with the kokutai, the doctrine that Japan is a unique society led by a divine monarch. 6 It empowered the authoritarian police of the prewar and wartime eras to arrest and imprison political dissidents. It was an ideal tool for an authoritarian government to silence its critics.

The judges and lawyers he faced in September 2004 had grown up in postwar Japan. They had been taught that the door to the country’s past as a police state had been firmly closed by the 1947 Constitution and other laws adopted to protect the people from the abuse of police power. Now their witness suggested that door might open again. Professor Okudaira was not only the nation’s best-known expert on the law of free speech; he had also researched and written a definitive history of this repressive law at the heart of that dark chapter in Japan’s modern history. 7 The judges and lawyers were well aware of the standing of the celebrated scholar who spoke these words. In a sense, they were all his students.

Yamamoto requested the witness to explain what he meant when he said cases processed under Japan’s current laws could be “just like” the Peace Preservation Law. He replied: “I mean a process where individuals were arrested, prosecuted, found guilty, and imprisoned. The decision to prosecute was a secondary matter. The accepted practice was one of searching for reasons to arrest and for reasons to place individuals in detention while swirling them round and round through the system …. People think that those were the days of the Meiji Constitution and we don’t have that anymore. And I also believe that it would be no simple matter to return to the past.

“In my understanding of modern Japan, to pass special criminal statutes like the Peace Preservation Law, the Peace Preservation Police Law and others would be extremely difficult. We would have to consider their relationship to the Constitution and it would take great political power. Therefore, today the police must act under the ordinary criminal law. The ordinary criminal law exists in order to protect social order for ordinary citizens. This system to protect the social order could be turned around to manufacture criminal acts. In the future it is very possible that these developments could be controlled in a way to suit the state security police. Look at the present case. It clearly shows that just because we haven’t seen these things yet, doesn’t mean we won’t see them in the future.”

Was the old scholar spinning some sensational science fiction? Was it really possible that Japan’s police could easily disregard the protections so carefully laid out in the Constitution in order to “manufacture criminal acts”?

“Some might say that I’m a very old man and so I imagine these groundless fears,” he said. “But for a constitutional scholar, this is a serious matter. It is our job to think about the steps to take in order to prevent such fears from becoming reality.”

The witness had quietly converted the discussion of an abstract concept like free speech into the very concrete topic of abuse of police power.

Then Yamamoto picked up the theme of “other” provisions of the general criminal law and suggested that Okudaira’s prophesy of similar political use of other provisions of the general criminal law had already come to pass. “I’d like to ask about some specific cases,” she said. “For example, someone got into an argument in front of the U.S. Embassy and was then charged with the crime of assault. This was followed by a police search of that person’s home. In another case, an employee of the Health Ministry distributed political flyers near his home on his day off and was arrested for violating the National Public Employees Law.” What did the scholar think about cases like this?

“These days they can’t crack down on political acts with specific political motivations based on special criminal statutes, so they use things like the crime of assault or the National Public Employees Law. These are general statutes. They use these general rules for indictments and after arrests there are lengthy detentions. They can confiscate computers and gather information on a very large number of people … even though there is no Peace Preservation Law, a new, modern something can arise that could be very similar”. 8 With this, the direct testimony came to an end.

Like his explication of the constitutional status of free speech, Okudaira’s declaration of his fears was not unusual. Similar fears resided in the breast of nearly every scholar who had chosen the path of constitutional studies. Back in March, when a couple of young scholars were inspired to draft a declaration condemning the Tent Village arrests, they gathered the signatures of 56 more senior colleagues within a few days. To one degree or another, they all shared the same fear and sense of crisis. After all, the revolutionary declarations of the 1947 Constitution were just words. The grave danger that would arise if the authorities chose not to follow those words could be seen most clearly by comparing them against the reality of what had come before. Due to his personal history and memories of the war years, Okudaira’s fears had very deep roots.

Footnotes

- Okudaira, Living the Constitution [Kenpō wo Ikiru] (Tokyo: Nihon Hyōronsha, 2007), 33.

- A list of Okudaira’s “major publications” that appears in a 2017 volume published in his honor runs to nearly forty pages in rather fine print. Yōichi Higuchi, Tōru Nakajima, and Yasuo Hasebe, eds., The Dignity of Constitutionalism: Themes from the Constitutional Philosophy of Yasuhiro Okudaira [Hō no Songen—Okudaira Kempōgaku no Keishō to Tenkai] (Tokyo: Nihon Hyōronsha, 2017).

- Okudaira’s opposition to war and commitment to defend Constitution Article 9 were underscored when he joined eight other prominent intellectuals to form the “Article 9 Association” on June 10, 2004. See Hisashi Inoue et al., Constitution Article 9 Is Still Fresh [Kempō Kyūjō Ima Koso Shun], Iwanami Booklet 639 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shōten, 2004).

- Okudaira, Living the Constitution, 16.

- Quotations from Okudaira’s testimony are from the court transcript, September 9, 2004.

- For a complete report on this era and enforcement of the Peace Preservation Law, see Max M. Ward, Thought Crime: Ideology and State Power in Interwar Japan (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019). See also the writings of Patricia Steinhoff.

- See, e.g., Yasuhiro Okudaira, A Brief History of the Peace Preservation Law [Chian Ijihō Shoshi], (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 1977; republished, Tokyo: Iwanami Shōten, 2006).

- In their zeal to silence opposition to the Iraq deployment, the police charged people with otherwise minor violations in a number of cases. For example, a student in Kyoto was arrested for making a false statement on his apartment lease because he did not notify the landlord that he might be making antiwar flyers in that space. Another was arrested for making a false statement to the police because he presented a driver’s license that showed a previous and no longer accurate address. Other cases included the prosecutions of Akio Horikoshi and of a retired high school teacher charged with causing a delay of a few minutes at a graduation ceremony. There were others. See Masatoshi Uchida, Is This a Crime? Thinking About “Arrests for Handing Out Flyers” [Kore ga hanzai? “Bira kubari de taiho” wo kangaeru], Iwanami Booklet 655 (Tokyo: Iwanami Shōten, 2005).

Lawrence Repeta has served as a lawyer, business executive, and law professor in Japan and the United States. The primary focus of his advocacy and research is transparency in government. He has served on the board of directors of Information Clearinghouse Japan, an NGO devoted to promoting open government in Japan, and the Japan Civil Liberties Union.