Issue:

September 2023

Long-time member Bradley Martin delivered the following eulogy at the FCCJ-sponsored Mike ‘Buck’ Tharp memorial evening on August 30.

What we have in our club’s current regular membership appears to be a generational split. Gone are most members of the older generations – notably the war-and-uprising “bang bang” correspondents who founded the club at the end of World War II and the beginning of the Occupation and who, right up through the Korean and Vietnam wars and the South Korean democratization movement, gave it much of its fame. Those world-traveling adventurers, who in earlier times made the FCCJ an exciting – sometimes even wild and wooly – place to spend time spinning and listening to yarns about real adventures, if they’re not literally gone are officially old, approaching if not already past usual retirement age. That’s one group.

The other group: In foreign media organizations we have a new generation of people who take conscious and vocal pride in never setting foot, much less breaking bread or raising a glass, in the club’s food and beverage facilities. We can point to multiple likely factors behind this, such as an explosion of culinary alternatives in Tokyo, but also including:

- Japan’s replacement by China in Western nightmares about upstart Asian countries – nightmares that used to guarantee bestseller status for books with titles such as Japan as Number One and The Japan That Can Say No.

- A correspondingly narrower concentration of interest in the Japan story on the part of foreign readers, leaving correspondents to focus their output on those readers who are involved in finance;

- The gradual replacement of Tokyo by Seoul as the home base for correspondents who cover northeast Asian general news and geopolitics;

- The long-overdue rise in women’s rights that has inspired many news outlets to name women – many of them coincidentally mothers who need to go straight home from work – as correspondents.

- A concurrent shift to more domesticated male correspondents, who also need to go straight home from work and attend to the kids and pets (and who, since 2020, when remote work was expanded to deal with the pandemic, have been spending even more time at home).

The preponderance of the Tokyo correspondent population has changed from roaming to settled. Compare China’s Yuan Dynasty, founded by Mongol horsemen, with its successor, the Ming, which came to power following an uprising by Chinese tillers of the soil.

We may be looking at a cyclical phenomenon. Members who pay their dues while using the club solely for attending meal-less PAC functions may give way to a new generation of adventurer/storytellers. That depends to a great extent on what happens regionally and globally and it isn’t within our control.

My guess, though, is that what we’re experiencing is not merely cyclical but, as in the case of the now tomblike Washington National Press Club, a permanent change, which would mean that the bare handful of still-active old-time newspersons who still gather eagerly at the FCCJ’s round tables, consuming booze and telling and listening to stories, before long will be gone forever.

History does tend to move on and we can’t stop it, but we can celebrate our memories of the great bygone days, particularly on a day like this when we mark the departure of one of our most prominent hail fellows well met.

Mike Tharp came from people who kept moving. His mama Carrie May was from her early teen years a trapeze artist, along with two brothers, with a family-owned traveling circus. She saw 46 U.S. states before she was 20. “Half of who I am is her,” Mike wrote. Here’s the opening of a poem he wrote about his mother in 1978 called The Girl Who Never Fell:

On those nights

the clowns were your cue

and when they shambled off

fumbling for Bull Durham sacks

their watermelon smiles

now greasy with sweat

you went on

Even a trapeze act

can become just a job

but when you stood

in your turquoise tights

on tiptoe in the ramp

looking over your brothers'

broad sequined shoulders

At the sawdust and smoke

spun by spotlights

into weightless gold

hearing your names shouted

above a hundred murmurs

and feeling the bellyflies

that always fluttered then

On those nights

there was nowhere else to be

and nothing else to do

except again to fly

from the wrists and hands

of one brother

to the other

And back and forth again

As for his dad, who was a railway detective, Mike memorably wrote this:

Papa was a god.

He wore a .38 snub-nose police special to work every day in a shoulder holster. For nearly 40 years he was a special agent – a railroad bull – for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway in Oklahoma City, Kansas City and Topeka.

Until his first heart attack at age 65, he never worked out. Yet, at six foot two, 195 pounds, he was a cross between Tarzan and Superman. He had a four-pack, softball-sized biceps and a manta ray of black hair across his chest….

He was also a lifelong subscriber to The New Yorker, read the dictionary at lunch and turned me on to Catch 22 when I was college….

We were used to him being out of town. He'd get a call in the middle of the night, grunt into the phone and start dressing. He always had a bag packed--he called it a “grip.” Then he'd head off to a freight car derailment, a card sharp on the Super Chief, a fight on the El Capitan, an employee trying to scam the railroad….

He styled himself after the 1940s actor Ronald Colman, with a pencil-thin mustache. A lot of people thought he looked like Clark Gable, without the jug ears….

He was not the strong silent type. He loved to talk and laugh. Especially at himself…. Once, after he got his eyes dilated, he went into their bathroom. “I looked down and there were two of them,” he told us later. “Being a proud man, I reached for the bigger one. It wasn't there.” …

He was my scoutmaster in Boy Scouts. In 1956, on the way to a scout meeting, he was talking about knots. The radio on our push-button Plymouth suddenly started playing “Jailhouse Rock.” Papa must have noticed me starting to dance in the passenger seat. He leaned over and switched off the radio. But from then on, I was hooked on Elvis. His fave was the Mills Brothers.

For being a lifetime lawman, Papa was fascinated by bad guys. In the bathtub he sang, “I am the king of the outlaws, as I ride, ride, ride!” He read a book called The Big Con several times. He loved the movie “The Sting.” He collected WANTED posters from the early 20th century in the Santa Fe files, especially of train robbers.

He loved a party, often starting one himself. When my friends came to visit, he greeted them by popping open a Coors in their faces and handing the can to them. Somehow, he got hooked on hats, and we had 15 or 20 hanging in the kitchen. As the Coors flowed, we swapped hats.

He was always there for us. He picked me up in Kansas City when I came back from grad school in Wales. A few months later he drove me back to that same city, this time to be drafted.

He visited me in Tokyo in 1979. Through a public affairs buddy at the embassy, we got a private meeting with Ambassador Mike Mansfield. The ambassador mentioned that in the 1930s, he used to “ride the rods” – to get free passage on rail cars.

“I used to run people like you off my railroad,” my dad said. We all laughed….

The first time I'd ever seen him look old, the man for whom words were all sat on the couch and said, “Michael, I can't remember the words.” A month later he died of a second heart attack. When we … were lifting his coffin from the church to the hearse, a long, lone train whistle skirled through the pines. We all stopped, looked at each other, then carried him on.

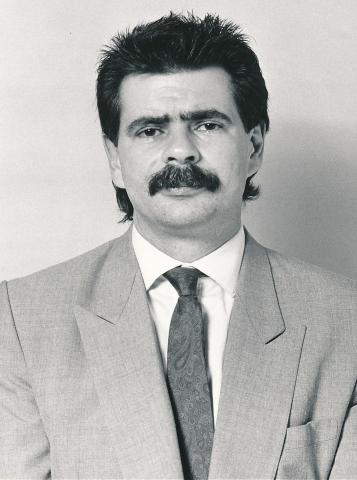

I never met his mom, alas, but was honored to meet Papa Gene Tharp during his Tokyo visit. You can see so many influences from the two of them here: Mike’s showman impulses and his travel bug; the physical details, from muscles to moustache; the self-deprecating good humor; the love of a party; making sure to be there for those you should be there for – and the words, always the words.

Mike chased the words very early as a copy boy for a Kansas newspaper. He became a world traveler first as a graduate student when he left his native western United States to study at a university in Cardiff, Wales, where he honed his natural-born skills as a poet.

And then he went to Vietnam for his first war. The Army had the sense to assign him a job suited to his background: Army newspaper work. He did well, left with a Bronze Star pinned on him.

And after he returned to the United States and got a domestic start at The Wall Street Journal, his intensive exposure to Asia was noted and acted upon. The paper dispatched him to Tokyo as the paper’s bureau chief – to replace Norm Pearlstine, who I hope has been able to wake up in the middle of this Vancouver night and join these proceedings via Zoom.

Mike wrote as follows about some of his early Tokyo reporting in 1978 at Narita, where protests by farmers reluctant to lose their farms had been going on since 1965.

Atypically for Japan, a consensus had not been reached among those affected by the construction. The protests intensified as Narita's opening drew near. That spring, along with my Wall Street Journal partner Masayoshi Kanabayashi and Tracy Dahlby of the Far Eastern Economic Review, I went to report on the trouble. Some 6,000 protestors turned out, and even more policemen. Usually the two sides moved in kabuki-like choreography, the protestors snake-dancing, arms locked, right up to the cops, who held their ground. It was more carnival than crusade. We interviewed several people during their breaks for rice balls and green tea, then took a train back to Tokyo to file. In the following few days, the protests turned violent, with riot police wading in to the protestors with shields, batons and water cannons and protestors throwing rocks and firebombs. Even so, the airport opened in May.

There were more trips to Narita. The staff of the Baltimore Sun bureau, Hideko Takayama and I, went along. The Sun’s office and the Journal’s were on the eighth floor of the old Nihon Keizai Shimbun Building in Otemachi, in what was then informally called the Nikkei Gaijin Ghetto. Other ghetto denizens were FEER, the Financial Times, Economist, Asian Wall Street Journal (a separate bureau until 1986), New York Journal of Commerce, the Fairfax papers Sydney Morning Herald and Melbourne Age and Toronto’s Globe and Mail. Multiple times a week, finishing work around the same time, a bunch of us would head out of the ghetto to drink, whether starting in a Japanese watering hole in the building or across the street or heading immediately down to Yurakucho and the FCCJ, which I believe either Mike or Tracy Dahlby may have been first to nickname the “Fuckidge.”

The ghetto rats were by no means the only correspondents converging upon the club’s main bar in the evenings. Correspondents of the world’s leading newspapers drank there regularly, regardless of where their offices were.

Clyde Haberman, who had an office elsewhere, represented the New York Times; Sam Jameson, ditto, the Los Angeles Times. Some used the club workroom as their office and popped into and out of the main bar all day long for coffee and then joined tables in the evening. In that latter category for a long while was Peter Hazlehurst of Singapore’s Straits Times, who had been kicked out of India while representing The Times of London. The AP, Reuters and AFP bureau chiefs lunched together daily, with wine, not in the highly affordable main bar (900 yen for a correspondent’s lunch) but in the upscale dining room.

And it was not just the Western mainstream press. Representatives of various Soviet news organizations had been given regular membership status and several of those enjoyed their drinks with the rest of us. (When the Iron Curtain fell, they revealed to us what their ranks had been in the KGB or other intelligence agencies.)

Sometimes members of our merry band would stay on telling stories in the club quite late, long after last order and after the departure of the Main bar staff, leaving only a single front desk person to watch over us, more or less. The club in those days kept hot coffee and a fridge full of beer and sandwiches on the back edge of the bar and we signed chits for whatever we consumed after hours.

Other nights we would move on from the club, after a decent interval, to Roppongi, in particular to Kento’s – a rock bar. Geoffrey Tudor, international PR chief for Japan Airlines, a club associate member and an honorary Gaijin Ghettoite, had been a pioneering rock impresario in the U.K. earlier in his career and he was able to fill the rest of us in on who was who in the musical world. (Geoff was helping me prepare for this evening but he was taken ill with Covid. We hope he is participating via Zoom.)

To learn more about how we spent our leisure time back then, check out an old article of mine in the Number 1 Shimbun, Salute to the Gaijin Ghetto Rats.

Among our old group, not only Buck Tharp but others before him have passed on. They include Richard Hanson of the FT, Charles Smith of the FT and FEER, Al Cullison of the Journal of Commerce and John Slee of the Morning Herald. Richard and Charles were still based in Tokyo when they left us – like Mike, far too young – and we held gatherings much like this one to remember them. Their widows, Keiko Hanson and Katsuko Usami, have honored Mike and our club by attending tonight.

I mentioned story-telling. Mike, as you will remember, had more than his share of stories to tell. I was along for the genesis of many of them, in Korea, in the 1970s and 80s. Here he remembers demonstrations:

In November 1987 I covered antigovernment, pro-democracy protests in Seoul for U.S. News & World Report. By then I'd been to South Korea about 45 times, starting in 1976, and to North Korea once, in 1979. I'd watched as South Korea moved from dictatorship under Park Chung-hee to military autocracy under Chun Doo-hwan. The protests had started in June 1987 and swelled month by month. Besides university students – who had become the voice of the democracy movement – these demos were joined by blue-suited office workers, housewives, ministers and others. Thousands of us were jammed together on Seoul's wide main avenue, outside the U.S. embassy. Protesters were shouting pro-democracy slogans. Suddenly, the police unleashed pepper spray on the crowd. At once, most of us started weeping and coughing. I covered my mouth and nose with a bandana, scribbled a few lines in my notebook and ran for fresh air. Soon Chun was pushed out of office and the new president yielded to more political liberalization. It was a highlight of my reporting career.

After Mike left Tokyo in 1990, following his term as club president, his U.S.-based career proceeded through several phases that included various combinations of reporting, editing, studying and teaching. See Tracy Dahlby’s brilliant obituary for more on that period. (And, by the way, Tracy has entrusted me with his Number 1 Shimbun fee for that obit, with which I can buy at least the first round at the nijikai in the main bar.)

Mike’s Vietnam War experience stood him in good stead in one major activity of the long post-Tokyo period of his life: covering wars. There were a lot of them and he was usually there representing U.S. News or, later, the McClatchey chain, for which his main job was editing the Merced, California, newspaper. Again, for details see Tracy’s obituary.

But in the end Buck came to suspect – and many of us friends tended to agree – that Uncle Sam had signed his death warrant in Vietnam in the form of Agent Orange and/or other color-coded defoliant poisons that the United States weaponized during that conflict. He wrote about this issue eloquently, but without personalizing it, for Asia Times and other publications.

He got around to personalizing things toward the end, when he was writing about his bone marrow cancer for people he knew personally – on Facebook, for example:

Well, hell, there goes my goal of becoming a male stripper in my dotage.

Ten chemo injections over the past five days raised roseate chain-mail blobs around my belly, marring my dreams of glitter and a silver pole.

The chemo kills bone marrow cancer. It also kills red and white blood cells and platelets, to wean those messengers of life to my heart from the Dali-shaped cancer that's clogging my veins and arteries.

It was diagnosed a month ago. That explained why I've had severe shortness of breath since April 2020. Two stents inserted then didn't help much. I've been on oxygen tethered to a walker since May.

A covey of -ists tried to figure it out. Finally, a hematologist scraped my hip's bone marrow in late August.

Eureka.

Now I'm one week on chemo, three weeks off ….

Jeralyn has been a combo of Florence Nightingale and Nurse Ratched. My kids, close fam and friends make me feel like a Homecoming candidate.

This will last 4-6 months. Appreciate any good reads or flicks I might like.

Then I'll go with John Keats:

Can death be sleep when life is but a dream?

And scenes of bliss pass as a phantom by?

The transient pleasures as a vision seem,

And we think the greatest pain's to die.

And he closed with his trademark signoff:

Meanwhile Comma Peace

I can’t find all of his exact words on the day when I could sense from his Facebook post that he’d received the ultimate bad news regarding the efficacy of his treatment but I have remembered two. He wrote to the effect that there comes a day when you wake up and learn something for which the only appropriate comment is, “Oh fuck.”

As the late Georgia humorist Lewis Grizzard famously said of his own situation at the time of Elvis’s demise, I wasn’t feeling so good myself. Before I could get it together to drive from Louisiana over to Plano, Texas, and see Buck one last time, he was gone.

I’ve had my say now, but before we invite attendees to come up one by one and say some words of remembrance of your own, I’d like to propose a toast to our dear friend:

Well done, Buck! We’ll do our best to keep telling the stories. Meanwhile Comma Peace.

Bradley Martin joined the club in 1977 and since then has been based in a number of Asian capitals. He’s currently associate editor of Asia Times.