Issue:

Salute to the gaijin ghetto rats

An alumnus of two of the news bureaus housed in the old Nikkei Building in the 1970s and ’80s recalls fellow journalists who worked and played in its cramped quarters.

by BRADLEY K. MARTIN

The 1970s were a great time to be a correspondent assigned to the Tokyo bureau. Readers, viewers, listeners and editors throughout the industrialized world were turning their attention from the Vietnam War and its aftermath to business competition, and that meant Japan. By the end of the decade Harvard Professor Ezra Vogel could and did cast Japan as Number One, and achieve bestseller ranking in the bargain.

How had the Japanese done it? Where were they headed next with their overachieving economy? The world wanted to know. News organizations that had done without Tokyo bureaus suddenly put them on their must have lists. Quite a few of them found space in a corner of the Nikkei Building’s eighth floor.

One of the first was London’s Financial Times, which had operated a bureau there in the 1960s with Henry Scott Stokes as chief. That bureau had closed in 1967. Six years later, as former bureau chief Charles Smith recalls, the FT was back in the Nikkei, reopening jointly with the Economist.

The rush was on, and soon there was a critical mass, to the point where Nikkei tenants began proudly identifying them selves as Nikkei Gaijin Ghetto Rats. Among arrivals in the early 1970s was the Baltimore Sun. In those days, the regional newspaper serving Maryland maintained seven, sometimes eight, foreign bureaus. The Sun bureau in New Delhi had closed, and Tokyo became its replacement.

Hideko Takayama recalls that correspondent Tom Pepper tried repeatedly to hire her as news assistant. But Pepper operated out of his home. That seemed to her a recipe for mixing up news and household errands, so she repeatedly turned him down. One day “he called me and said, ‘Now you can start working for the Sun. I found our office at Nikkei.’” Takayama reported from there until 1980, when the Sun moved its bureau back to New Delhi in the (futile) hope of managing up close reporting of the war in nearby Afghanistan. She later became a correspondent for Newsweek and Bloomberg.

Quite a few other news organizations like the Sun (which now has zero foreign bureaus) looked for Tokyo office space and found it in the Nikkei Building and, later, closed their bureaus as hard times came to the Japan story and the news business. The list includes Hong Kong’s late, lamented Far Eastern Economic Review, New York’s Journal of Commerce, the Fairfax papers (Sydney Morning Herald, Melbourne Age, Australian Financial Review) and the Globe and Mail of Toronto.

“It was a quasi religious experience, enhanced by puffing on foul-smelling cigarillos.”

THE NIKKEI CROWD WAS a merry band, often partying together sometimes in the office. Jurek Martin, who was FT bureau chief and the 1985-86 FCCJ president, recalls that his “most contented times happened at about 4 p.m. for two weeks, six times a year, when Bill Emmott of the Economist emerged from the adjacent cubicle to watch the sumo tournaments on my office TV. It was a quasireligious and certainly cultural experience, enhanced by puffing on foul-smelling Wilhelm II Dutch cigarillos.”

Martin adds: “There was an immortal Chiyonofuji Wakashimazu battle lasting over two minutes, won by Wakashimazu, that left cigar ash everywhere and the Suntory Old bottle half empty. Of course, all this happened at a time of the London day when none of our nominal masters had even turned up to work. Anyway, the pieces I wrote on sumo and high school baseball earned far more kudos than anything on Komatsu tractors, so our times in front of the box were well spent.”

The building had a certain entertainment value, especially during earthquakes. Charles Smith, who after his FT stint worked there as bureau chief for FEER, recalls “standing at our window one day and watching the Mitsubishi Research Institute rocking gently, like a cargo ship tied to its berth.” His FEER colleague Robert Delfs adds that at such times “the Nikkei Building itself was boogieing back and forth, too. One time it dumped all my books off the bookshelves and onto the floor. I gather the amplitude of movement was exaggerated by the use of joints, which were intended to allow the building to sway, releasing stress.”

There were office romances, some leading to wedding bells. And often, after work, Nikkei denizens would repair to either the Club’s correspondent tables or a beer hall closer to the office. On weekends people liked to go to Roppongi, particularly to Kento’s a 1950s themed live rock ‘n’ roll nightspot. Kento’s is still there, according to Gwen Robinson, ex FT and now Nikkei Asian Review editor in Bangkok, “full of genteel obasan getting their rocks off.” That establishment may end up being a scheduled stop for a group of Nikkei Ghetto alumni gathering in Tokyo for an early July reunion.

Besides the FT and the Economist, papers that managed to maintain their Tokyo presence up to now even though the old Nikkei Building itself is long gone include Düsseldorf’s Handelsblatt and the Wall Street Journal.

IN 1976, MIKE “BUCK” Tharp and Masayoshi “Chief” Kanabayashi (Tharp likes nicknames) shifted Journal operations from a single desk in the AP office to a real bureau in the Nikkei corner. “To move in,” recalls 1989-90 FCCJ president Tharp, “we traveled the byways of old Tokyo, buying used furniture desks, lamps, a couch and two stiff chairs for visitors, filing cabinets.”

Eduardo Lachica and Billy Schwartz moved in around the same time to open a bureau for the Journal’s sister regional daily startup, the Asian Wall Street Journal. Prime space was all taken by then, so they drew a tiny windowless alcove which they had to share with the paper’s business side people. With appropriate Tokyo office space so hard to come by, the two scribes didn’t complain as they cranked out enough stories to fill half their paper.

Lachica’s productivity earned him a nickname borrowed from a famous pool player of an earlier generation, “Fast Eddie.” Only after he finally left Tokyo for Washington (sent off with a rolling party, a beer soaked bus tour to the pottery town of Mashiko), was he deservedly able to slow down a bit and play some golf. Talented reporters who also worked in the AWSJ bureau in its early years included Norman Thorpe who stayed only a year before opening the AWSJ’s office in Seoul and John Marcom.

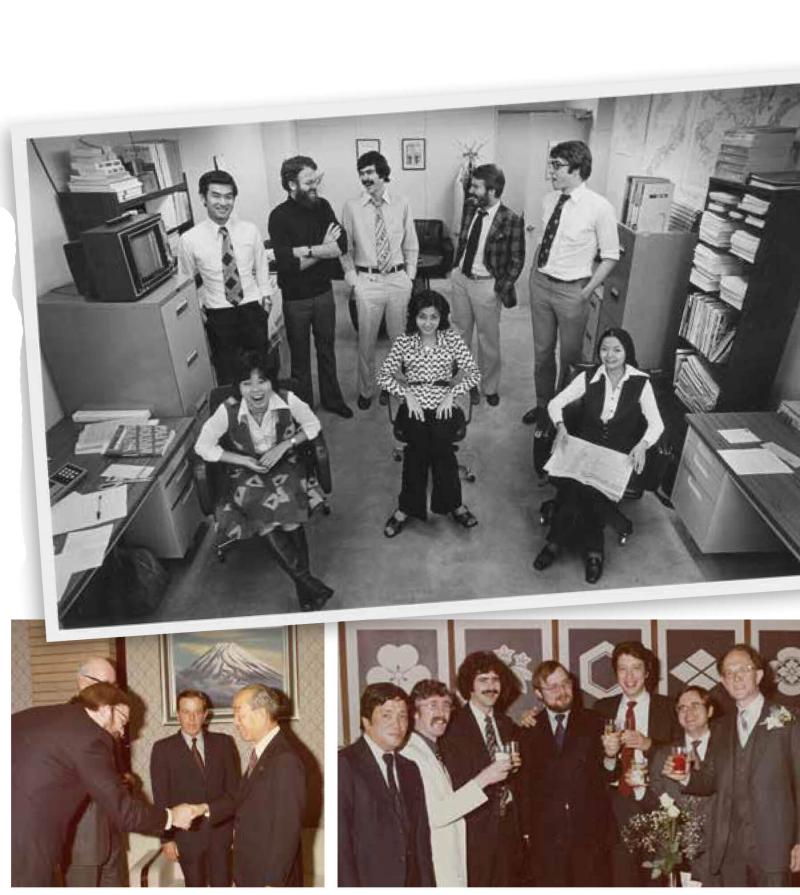

front row, Rumiko Kobayashi (the Sydney Morning Herald), Ryoko Fukutake (Wall Street Journal), Hideko Takayama (the Baltimore Sun); second row, Masayoshi Kanabayashi (WSJ), John Slee (SMH), Mike Tharp (WSJ), Doug Ramsey (the Economist), Tracy Dahlby (Far Eastern Economic Review). Below left, the author meets P.M. Takeo Fukuda while company Chairman Gary Black looks on. Below right, Eddie Lachica (Asian Wall Street Journal), honorary member of the gaijin ghetto Geoff Tudor (JAL), Mike Tharp (WSJ), the author, Tracy Dahlby, the late Richard Hanson (FT), and Charles Smith (FT) at whose wedding this was.

The building hadn’t been constructed for luxury. Rooms were generally small and simply outfitted. They often filled with toxic smoke due to correspondents’ habit of keeping tobacco products burning in their ashtrays while hunching over typewriters to pound out copy. The health authorities never showed up to put a stop to that.

One semiretired correspondent, asking not to be named for fear of offending Nikkei, recalls that his office “was a shithole.” Nikkei probably wouldn’t disagree. After all, the company tore the building down and replaced it. But that didn’t happen until the 21st century by which time several generations of correspondents had developed the ability to empathize with Japanese salarymen and OLs based on personal exposure to equivalent working conditions.

THE GENERAL SCHEME IN the Nikkei Ghetto was typified by the FEER bureau, where Susumu Awanohara, Kazumi Miyazawa and Tracy Dahlby (one of the then rare breed of American correspondents trained in Japanese), joined later by the late John Lewis after Awanohara’s move to Jakarta, squeezed into a room suitable for one or two.

People came and went, some working in the Ghetto for multiple publications over the years. After turning over the WSJ bureau to Urban Lehner when he left in 1980, Tharp returned a year later for a second tour in the building as FEER bureau chief.

Regardless of that continuity, new trends appeared for example, a developing industry emphasis on correspondents’ language abilities. The AWSJ in the early ’80s hired Chris Chipello, who had learned Japanese as a Princeton student. Around that same time the Japan raised MK (that’s an abbreviation for missionary kid) Steve Yoder started in the AWSJ bureau as part time interpreter, blowing away interviewees with his native Tohoku accent. The first story Yoder reported and wrote on his own, an in depth piece on the Japanese company Seiko, so impressed AWSJ management that he got promoted on the spot to correspondent.

Eventually the AWSJ staff was merged into a combined Journal staff. Lehner, back for a second tour in charge of the whole shebang, was the most devoted and accomplished student, ever, of Toshiko Oguchi, who taught Japanese in the office to generations of Journal correspondents. Lehner presided over an expansion that brought the number of journalists to 10 still including Kanabayashi, Chipello and Yoder, and with the addition of such future stars as Marcus Brauchli.

“A lot of American businessmen had decided for the first time that they needed to understand Japan,” Lehner recalls. “My editors were eager to run not just my business and economics and trade coverage but my neophyte discoveries of Japan and the Japanese. I knew I was on to something when the edit page ran a review I wrote of a kabuki play. Alas, America’s curiosity about Japan didn’t last long."

Bradley Martin was a Nikkei ghetto rat as Baltimore Sun bureau chief, 1977-80, and again as Asian Wall Street Journal bureau chief, 1983-86. His novel Nuclear Blues is due out shortly