Issue:

February 2023

How antisemitism took hold in Japan

Does antisemitism exist in Japan? The answer depends partly on how one defines the term. While antisemitism undoubtedly exists in Japan, it is difficult to pinpoint. Antisemitism in Japan takes a different form than it does in many other countries, owing to a specific history of how it has taken root among a very small minority of writers.

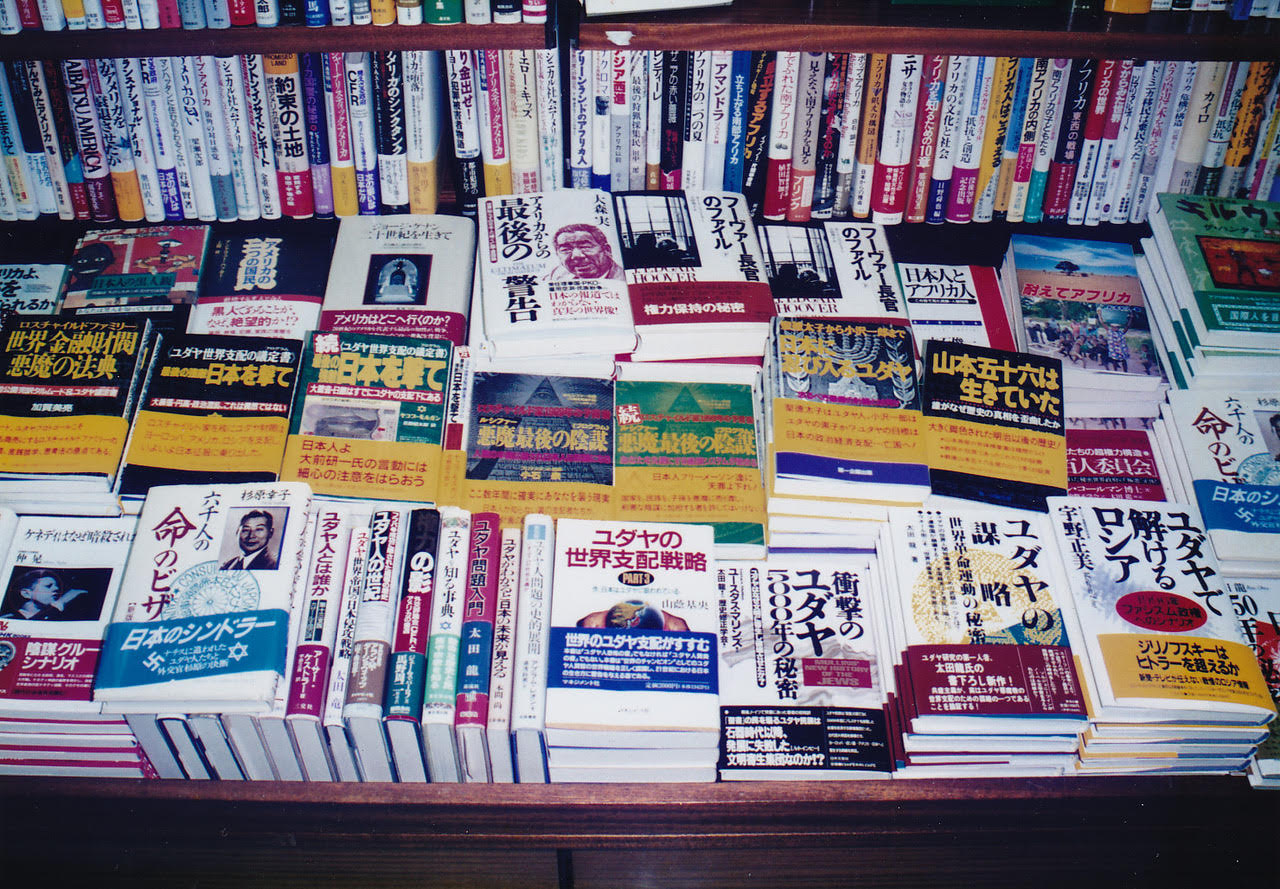

The photo below, taken in 1995, illustrates the problem. It shows a large display of several dozen Japanese titles about Jews and Judaism in one of Tokyo's largest bookstores. Serious academic books and biographies share shelf space with books espousing groundless conspiracies about “the Jews” and tips on how to emulate them to achieve financial success. As a researcher trying to understand how stereotypes and tropes about Jews interact with Jews living in Japan, I found the image confounding.

Such defamatory and derogatory conspiracies about Jews have been circulating in Japan since the 1920s, but they have come to be mixed together with accurate representations and serious discourses.

According to publishers' sales figures, the all-time best-selling Japanese book on the subject is The Japanese and the Jews by Isaiah ben-Dassan. It was the best-selling book of 1971 and was awarded the Oya Prize for nonfiction. While the book was purportedly written by a Jewish person raised in Japan, Isaiah ben-Dassan did not exist. The actual author was a Japanese man, Shichihei Yamamoto. The book is essentially a political critique of Japanese society through fleeting and vapid references to Jews. Another book purportedly authored by a Jew, Aru Yudayajin no Zange: Nihonjin ni Ayamaritai (A Jew’s Confession: I Want to Apologize to the Japanese) by Mordechai Moses uses conspiracies and falsehoods to pursue historical revisionism, blaming Jews for Japan’s involvement in World War II and for its defeat. First published in 1979, the book’s 2019 reprint contains blurb from a former Japanese diplomat and a professor emeritus from a leading national university.

Both books capture three key features of conspiratorial and defamatory Japanese discourse about Jews since the mid-1920s: they are largely print-based, detached from actual Jewish experience and perspectives, and promote arguments that ignore the interests and perspectives of actual Jews.

Researchers have often called antisemitism in Japan “surprising”, perhaps because Japan has had relatively few Jewish residents since opening to foreign trade in 1854. With the exception of more recent Japanese Christian fundamentalist authors, there has also been an absence of religious conflict between Japanese beliefs and Judaism. In his important 1997 survey of Japanese attitudes towards Jews, the Israeli scholar Rotem Kowner observes that Japanese culture, history, religion, and society lack many elements that often form the basis for antisemitism elsewhere in the world. Yet, a decade earlier, American professor David G. Goodman wrote in the New York Times that, in his assessment, “Antisemitism has greater intellectual currency and respectability in Japan than in perhaps any other industrialized society.”

How, then, did antisemitic ideas and stereotypes manage to take root and become propagated among Japanese intellectuals and writers?

Antisemitism in Japan – unlike in Europe and North America – has a relatively short history. While depictions of Jews entered into Japan soon after it emerged from isolation in 1854, antisemitic conspiracies and tropes gained a foothold close to 60 years later. During the ill-fated 1918-1922 Siberian Intervention against the Bolsheviks, Japanese military officers encountered White Russian military officers, who blamed Jews for the Russian Revolution. Two Japanese officers in particular, Koreshige Inuzuka and Norihiro Yasue, both became aware of the notorious antisemitic forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, through Russian contacts. The widely circulated Protocols purported to be the plans for world domination by an elite Jewish cabal. Although disproved by British newspaper, the Times, in 1921, they were cited as fact by influential people around the world, including Henry Ford. Inuzuka and Yasue used their knowledge of the Protocols to claim expertise on the Jewish people, eventually gaining official recognition by the Japanese government.

Inuzuka and Yasue would go on to become the Imperial Navy and Army’s so-called “Jewish experts,” wielding influence over the Japanese empire’s policy towards refugees during the Pacific War. These two men represented a larger channel through which outright antisemitism entered into the highest levels of Japan: ideologues, officials, and politicians. While most Japanese people did not share in these beliefs and conspiracies, leaders in domestic and foreign policy disseminated them as fact. For instance, Kokusai Seikei Gakkai (the Association for International Political and Economic Studies), which published a series titled Kokusai Himitsu-ryoku no Kenkyu (Studies in the International Secret Forces), was funded by the foreign ministry and the German embassy, and comprised mainly military officials and ultranationalist ideologues.

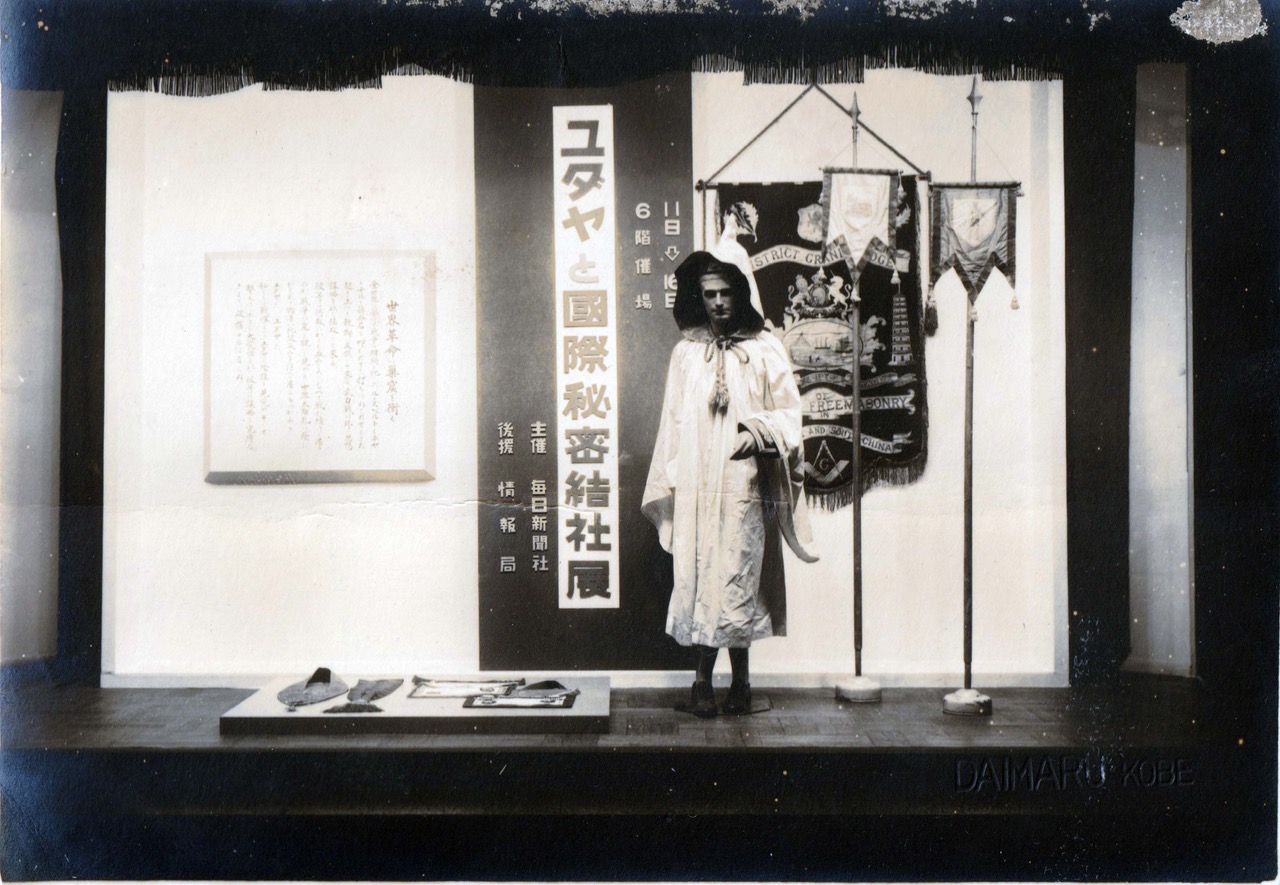

Because of their popularity amongst Japan’s political and military elite, many modern conspiracies and tropes enjoyed even wider circulation in Japan from the 1930s. For instance, just prior to the Pacific War, the government’s Information Bureau collaborated with the Mainichi Shimbun to sponsor antisemitic exhibitions at branches of Daimaru department store, promoting these ideas to the masses (although there is little evidence that more than a very vocal minority embraced such ideas.) Retired Lieutenant General Nobutaka Shioden ran in 1942 on a brazenly antisemitic platform for the House of Peers (now the Upper House), and received more votes than any other candidate in the election.

This sort of open antisemitism quickly declined in the postwar period as many of the people promoting antisemitism in wartime Japan subsequently lost their political cache. In addition, general and scholarly books on Jewish history, the Holocaust, and Judaism gradually became more widely available in the Japanese language. Japanese convert to Judaism, Abraham (Setuzo) Kotsuji, recounts in his autobiography that during the war, books seen as favorable to Jewish interests were often the target of censorship.

In the immediate aftermath of the Pacific War, the European Holocaust achieved little recognition in Japan. While Anne Frank’s diary was a domestic hit, it became so in a uniquely Japanese way. In their 1995 book, Jews in the Japanese Mind, Professors David Goodman and Masanori Miyazawa recount that Frank’s Diary of a Young Girl became a bestseller when it was published in Japan in 1952, but was not viewed as a story about the Holocaust. Instead, it was regarded as a cautionary tale about the general horrors of war – something that resonated with a Japanese audience in 1952. As Goodman and Miyazawa wrote: “…Anne’s image [in Japan] reflected the Japanese imagination at this time far more than it reflected the Jewish experience”.

The same could be said of many more postwar discussions of Jews in the Japanese media, many of which centered on Jews who existed only in the minds of certain Japanese writers This explains why those writers’ perceptions of Jews often seem surprising or unique.

These perceptions emerge from a complicated history, rather than any quintessential aspect of Japanese culture. The 1962 trial of Adolf Eichmann in Israel, as well as the Six-Day War (1967) both stimulated further discussion of Israel and Jewish people in the Japanese media. However, the success of Yamamoto’s The Japanese and the Jews in 1970 led to an increasing publication of books that peddled misconceptions and stereotypes. By the time of the short-lived economic bubble and subsequent crash between 1986 and 1992, explicitly antisemitic books suggesting that Jews were responsible for Japan’s economic ills were found in bookstores all over the country.

Professor David Goodman, in a 1989 academic paper, reviewed several popular magazine and newspaper articles that blamed Jews for economic and political problems, and offered this assessment: “None of these individuals or organizations has anything remotely resembling an antisemitic agenda or even a clear notion of who the Jews are. Their ludicrous caricature of Judaism reveals not malice, but appalling ignorance.”

By the early 1990s, Jewish human rights organizations in North America became concerned by the trend toward publishing conspiratorial and defamatory pieces about Jews in Japan, and began protesting to Japanese publishers. On January 17, 1995, Marco Polo, a glossy monthly magazine appealing to cosmopolitan and educated young professionals, published an issue that contained an essay by Masanori Nishioka, a medical doctor. This now infamous article, titled The Post-War World’s Greatest Taboo: The Nazi Gas Chambers Never Existed, denied the existence of gas chambers in Nazi concentration camps. For several weeks, Japanese newspapers and opinion magazines, otherwise occupied by the catastrophic Great Hanshin Earthquake, made little note of the article. However, following Marco Polo’s refusal to apologize or retract the piece, the Los Angeles-based Simon Wiesenthal Center began organizing against the magazine, and it was not long before advertisers pulled their ads. By the end of January, Marco Polo's publisher, Bungei Shunju, announced the magazine would cease publication and its staff reassigned.

A person involved in the protest against Marco Polo told me in an interview last year that there has been an “extended period” where, “no news is good news” as regards highly public episodes of antisemitism in Japan.

The photo near the top of this article represents, with some significant qualifications, a good summary of where things still stand today: a range of conversations by a small minority of Japanese writers about Jewish people that do not involve them, and for purposes that will do nothing to help them. Notably different from 1995 is that the most virulently antisemitic books, as well as those denying the Holocaust, are no longer found on store bookshelves. Instead, the internet has become fertile ground for the spread of antisemitism in Japan.

The protests that led to Marco Polo's demise may have made Jewish-related topics taboo in the media, but this did not lead to a wide understanding of the difference between conspiratorial fictions and legitimate discourse. Rather, the resulting chilling effect led most mainstream publications to avoid controversial Jewish subjects altogether. But this does nothing to stop anonymous or self-published authors, including Nishoka, who still maintains an active Twitter account. Amidst a dearth of accurate and positive representations of Jews in the public media, the propagation of conspiracies and stereotypes elsewhere seems set to enable negative perceptions to live on.

The lack of discussion of Jewish issues in the Japanese media has to be set against a concerning uptick in online antisemitism, as well as self-published books targeting increasingly niche audiences. Perhaps now is the time for Japan’s foremost thinkers to encourage informed and open conversation on this topic, lest the lack of discussion of Jewish issues in open and official channels encourage even more conspiratorial activity.

Dylan O’Brien is a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology at the University of California, San Diego. His research examines how representations of Jews and Judaism in Japan interact with Jews living in Japan.