Issue:

December 2022

Japan’s long-term economic decline masked by debate over the yen’s dramatic decline against the dollar

We all know - or think we do - why the yen recently hit a 30-year low against the dollar, and why it remains the "sick man" among Asian currencies. It is because a stubborn Bank of Japan (BoJ) insists on keeping interest rates at rock bottom levels in Japan when they are shooting up elsewhere. Or is it?

Not according to currency experts who spoke at a recent Deep Dive event at the FCCJ. They argued that what Japan should worry about is not so much yen weakness itself as the serious decline in the nation's manufacturing and export competitiveness that enyasu is pointing to.

If the speakers – Credit Suisse Securities (Japan) chief economist Hiromichi Shirakawa and economics lecturer and Toyo Keizai special correspondent Richard Katz - are right, then yen weakness will not go away soon, even if the currency gets up off the floor and onto its knees at the very least.

Economic policymakers and commentators, the speakers said, need to shift their attention from short-term fluctuations in the yen-dollar rate and focus instead on what this says about Japan's long-term economic decline and what, if anything, can be done to reverse it.

The huge differential between the U.S. Federal Funds rate of 4% and the near-zero official interest rates in Japan is in part to blame for the yen's relative weakness against the dollar (and for the slide of other currencies versus the dollar), according to Shirakawa.

But that means the yen is undervalued by around ¥20 to the dollar and, on the basis of interest rate differentials alone, it should be trading at ¥120-125 to the dollar, he said. But its recent plunge to ¥150 is something else. Japan's erstwhile “Mr Yen”, Eisuke Sakakibara, predicts that it could even hit ¥170.

Shirakawa, a former senior BoJ official, and Katz, who lectures on Japan at two U.S. universities agreed this Japan should be most concerned about that “something else”.

Shirakawa said the “secular decline in competitiveness of the Japanese economy” lies behind much of the yen’s decline. Japan’s manufacturing sector is weakly positioned in regional and global supply chains because of shortages of parts, especially semiconductors, since the Covid-19 pandemic.

Even though a weaker yen should, in theory, be making Japanese manufactured exports more competitive in international markets, in reality export volumes have not improved, while the penetration of imported consumer goods into Japan has remained high, despite their higher cost in yen terms.

In short, Japan's terms of trade have deteriorated (meaning that export prices have risen less than import prices), partly because of the exchange rate effect and partly because Japanese exporters have tried to preserve market share by holding prices steady rather than raising them.

Weak exports and rising imports mean that Japan's trade and current account balance has deteriorated, and that has adversely impacted the nation's fiscal position, Shirakawa said. A fiscal crisis could occur if the yen falls below ¥150 to the dollar and the BoJ should make that risk clear, he added.

Katz agreed that the yen exchange rate “reflects a fundamental weakening of Japan's economy”, and the fact that Japan's former trade surplus of 1.2% of GDP has now become a deficit of 0.3%. The weaker yen “is not doing what it should be doing” because Japanese products have become less competitive, he said.

Katz referenced falling sales of Japanese electronic products, which he said “crashing” behind those of competitors both for products made in Japan or in Japanese plants overseas. There are no Japanese smartphones or tablets leading the way, and nor is there a Japanese answer to Tesla, he said.

Japanese firms are not investing efficiently in digital technologies that could boost productivity, and are not increasing wages, which would raise consumption, Katz said. A quarter of a century of a century of low interest rates has bred “zombie” companies that cannot survive once interest rates are raised, he added.

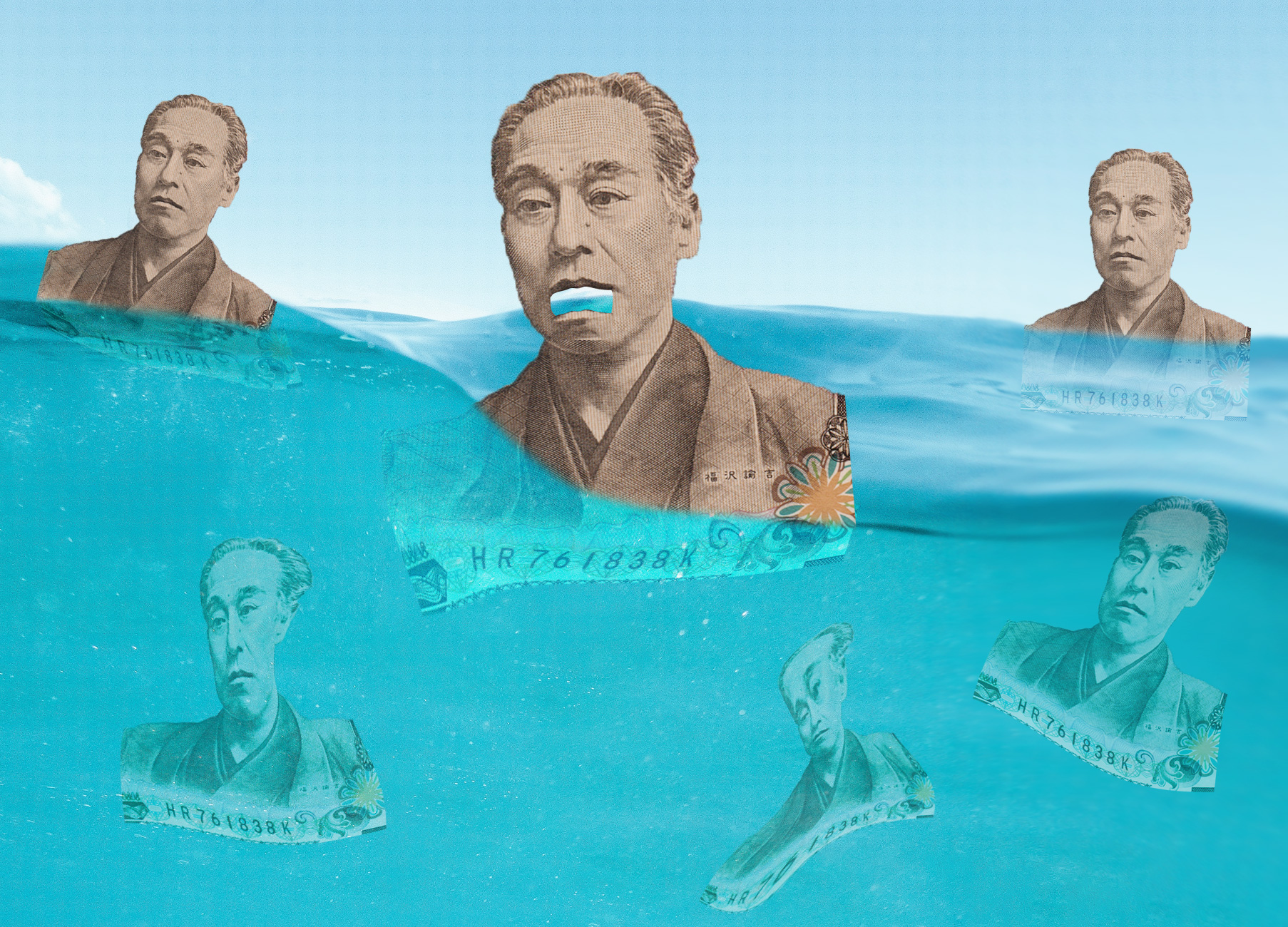

It is difficult to say who was the more pessimistic about Japan's prospects. Shirakawa was gloomy, saying that Japan could suffer either a fiscal crash or slide into a “contractionary equilibrium. Katz, meanwhile, suggested that Japan would not so much “fall off a cliff as walk slowly into the sea”.

They agreed that the blame lies not with the Japanese people, who are innovative and entrepreneurial, but with sclerotic attitudes inside the government and bureaucracy. If Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s “new capitalism” succeeds in boosting innovation and improving income distribution, Japan can save itself from irreversible decline, Katz said. But, he added, he is not betting on that happening.

Anthony Rowley is a columnist and contributor for The South China Morning Post.