Issue:

December 2022

Japan’s revisionists label Lieutenant General Kiichiro Higuchi a hero for saving wartime refugees, but their tenuous account is a willful misuse of Jewish suffering

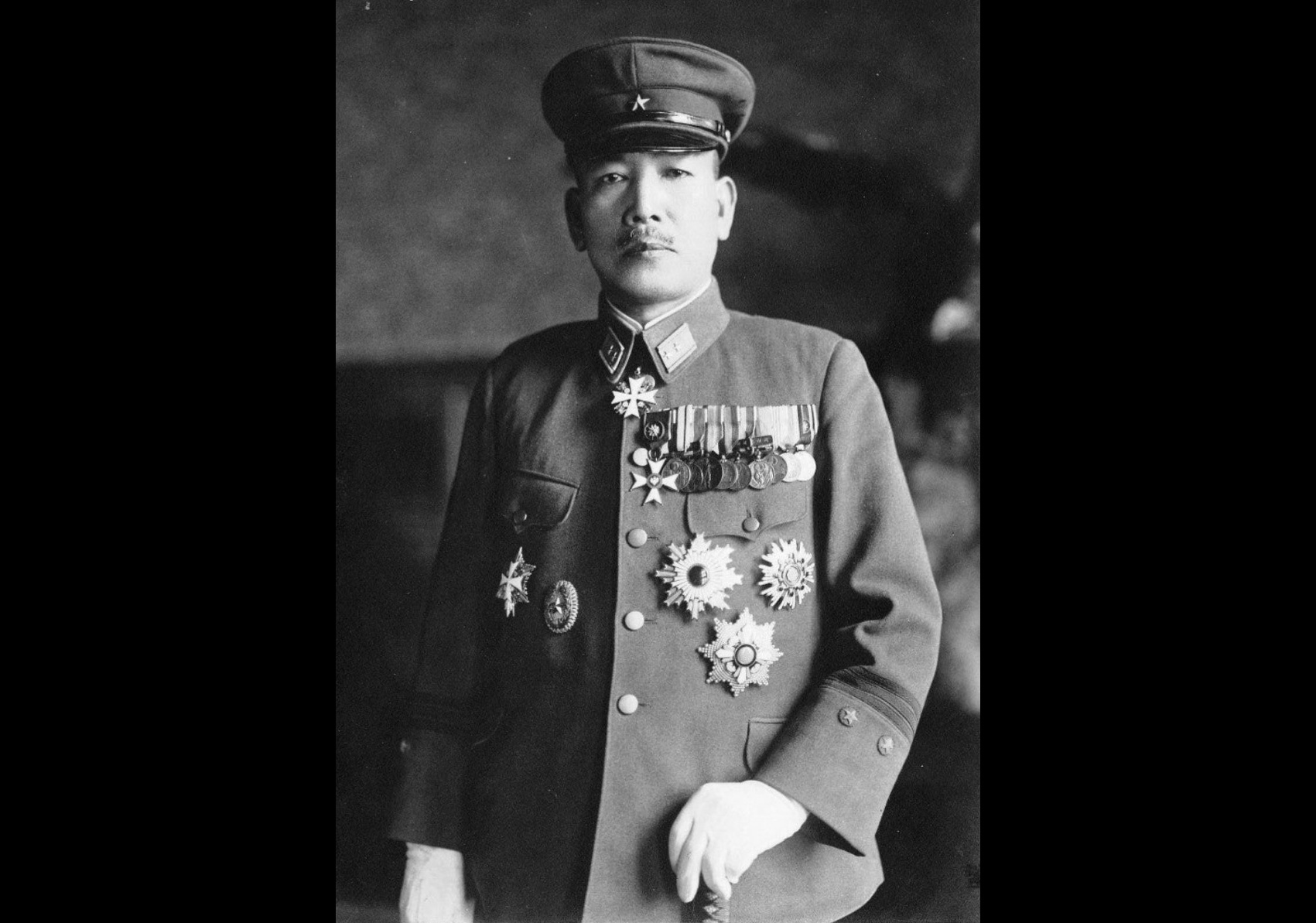

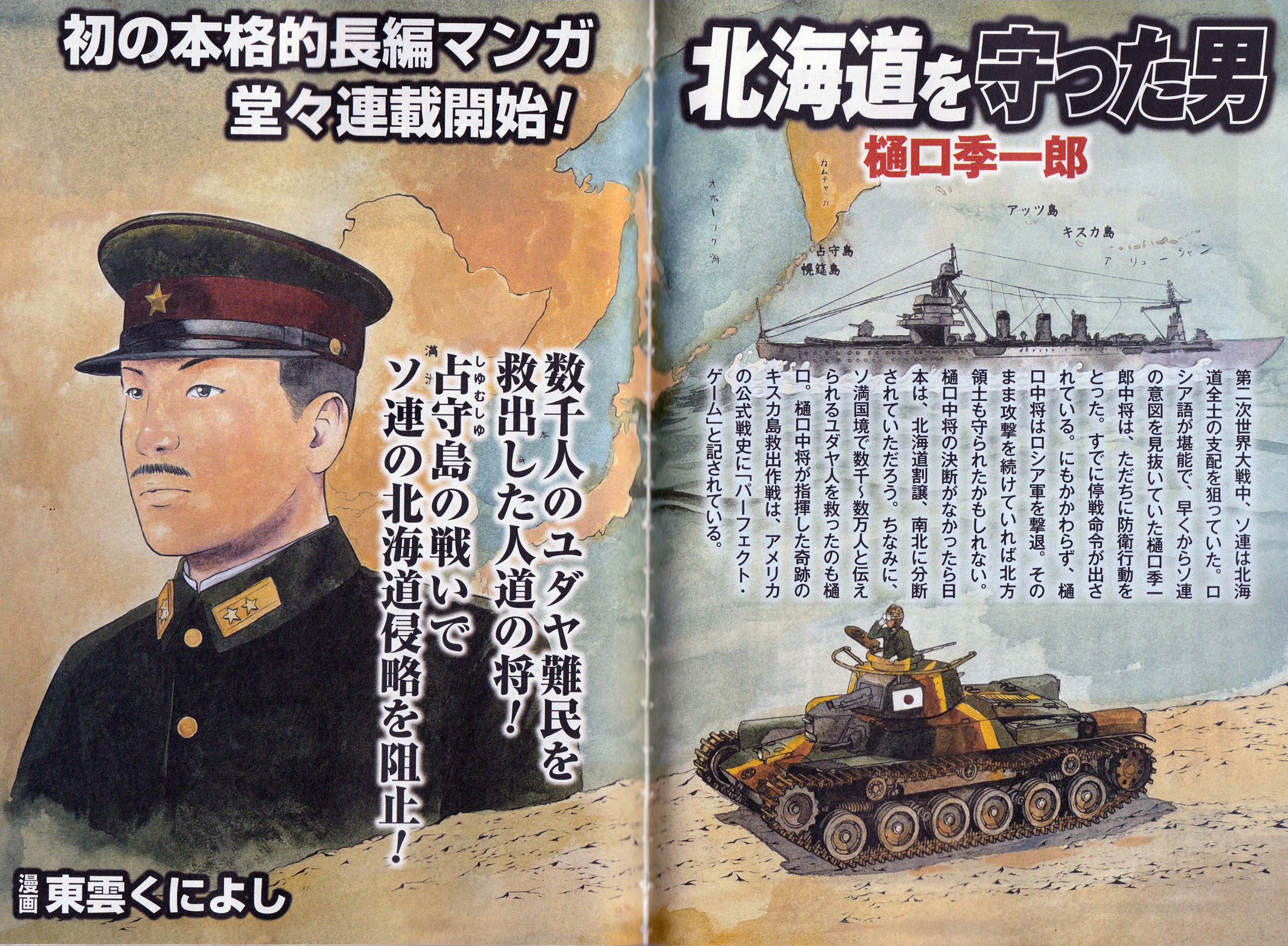

Japan has a new national hero. In recent years, Lieutenant General Kiichiro Higuchi of the now-defunct Imperial Japanese Army has become a well-known paragon of virtue. His exceptionally benevolent deed has been extolled in dozens of articles appearing in national newspapers and in the foreign press, in magazines, books, documentary films, and even a manga series currently in print. During the last few months, the commemoration of Higuchi has culminated in a conference, music concert, and ceremony last October unveiling a bronze statue of him on his home island of Awaji. But, does Higuchi merit such honors?

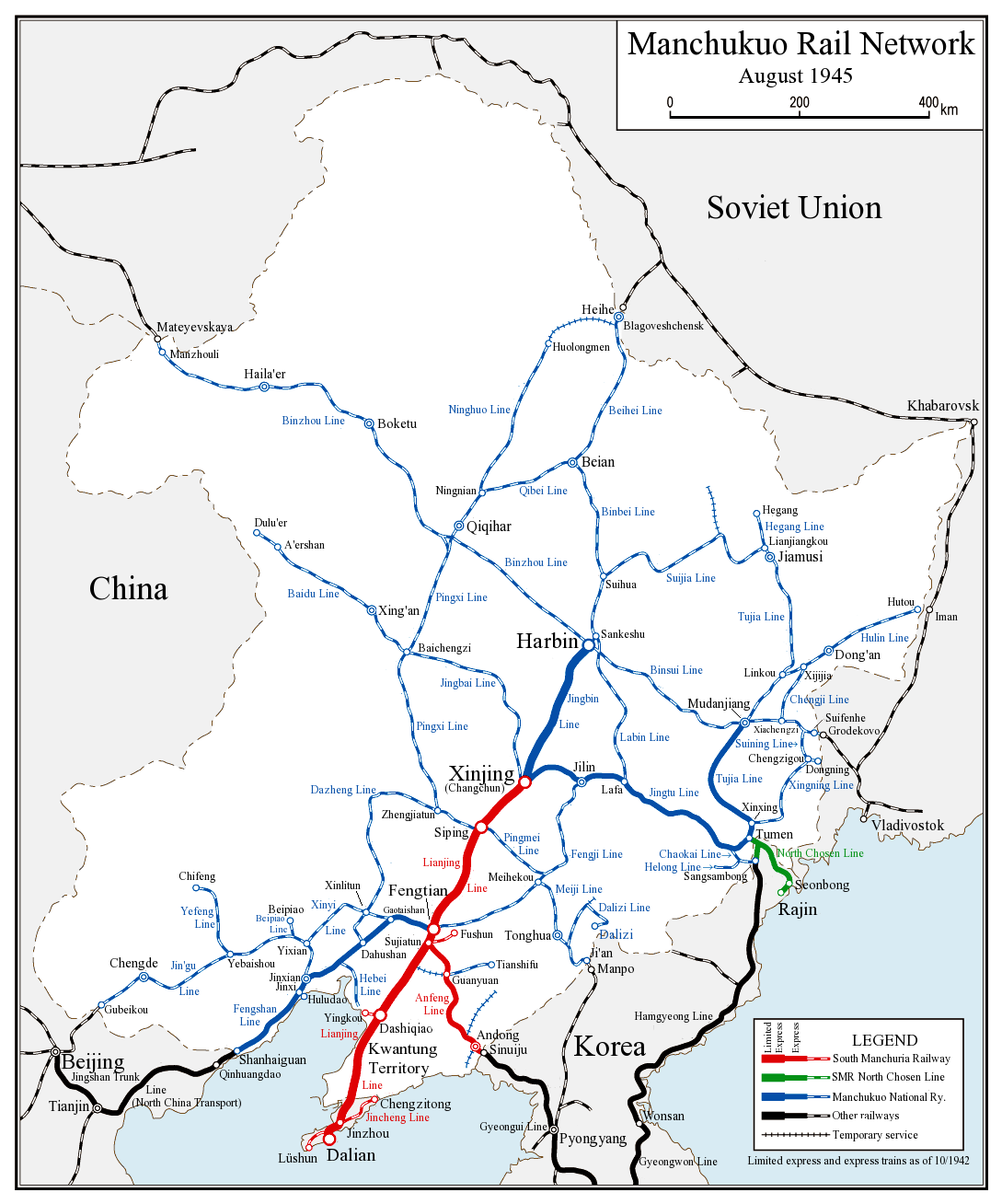

Born in 1888, Higuchi ended his military career as the commanding officer of the Sapporo-based Fifth Area Army. As the person in charge of Japan’s northern border in August 1945, he was involved in the desperate defense effort against the Soviet Army. His fame, however, stems largely from a brief episode seven years earlier. At the time, Higuchi was in charge of the Special Branch of military intelligence in Harbin. It was a major city in Manchukuo, the puppet state established and controlled by Japan in China’s vast northeastern region of Manchuria.

In this capacity, the story goes, Higuchi was informed of a large number of German Jewish refugees stuck in the freezing border Soviet town of Otpor (present-day Zabaykalsk) situated opposite the Manchurian town of Manzhouli. There were “about 20,000 of them,” he wrote. Escaping persecution by the Nazi regime, they crossed Siberia by trains at the peak of the winter of 1937-38, seeking to enter the safe haven of Manchukuo. “It was clear that if these refugees were left alone,” Higuchi recalled years later, “it would become a matter of life and death.” With this sense of urgency, he resolved to help them and discussed the matter with the chief of the Harbin delegation of the Manchukuo Foreign Affairs Office. When permission arrived, Higuchi provided the refugees with trains and food, and so “saved their lives.”

To be sure, this episode of rescue and benevolence is moving and seems to merit tremendous honor, even if posthumously. Regretfully, however, many gaps in the story make it unreliable and render Higuchi’s heroism more than questionable. The first and foremost gap involves the sources, as the only full reference to this episode comes from Higuchi himself. Intriguingly, there is not a single person who ever testified to having been stranded in Otpor and entering Manchukuo due to Higuchi’s intervention. Likewise, there are no official Japanese documents that mention the arrival of this group of refugees during the time Higuchi served in Harbin.

The second gap involves the historical facts about the Jewish flight to East Asia and its scale. Overall, some 20,000 Jewish refugees from Germany, Austria, and Poland did seek safe haven in East Asia, but the vast majority of them arrived while boarding ocean liners in Italy. Moreover, most of them did so after the Nazi pogrom – “Kristallnacht” – in November 1938 and at least eight months after the episode described by Higuchi. There are some indications that a few dozen Jews reached the Manchurian border by land in 1938. Nonetheless, they did not face any risk to their lives at the time, nor was any official policy in force to prevent them from crossing into Manchukuo territory.

In retrospect, Higuchi’s involvement in this episode, if it indeed occurred, was no more than a clerical approval for the passage of a small group of refugees some 18 months before the outbreak of the war in Europe. It was certainly not a matter of life and death. If refused, the refugees could have continued to Vladivostok and then headed by sea to Shanghai, a war-torn city that did not require visas for entry, the only such port in the world at the time.

This is not to say that Higuchi did not deal with Jews during his stint in Harbin. Upon his arrival, this city still hosted the second-largest Jewish community in East Asia. However, the Jewish population had fallen sharply since Japan seized the region in 1932. One way in which Japanese authorities exerted control over the local population was by turning its ethnic groups against each other, especially the White Russian community against the Jews. In one notorious case, in which the son of a local Jewish hotel owner was kidnapped and murdered, its echoes reached the League of Nations.

In the aftermath of this murder, the Japanese authorities temporarily stopped their maltreatment of local people. Higuchi seemed particularly positive towards the Harbin community and soon became involved in launching the first Far Eastern Jewish Congress in December 1937. Whatever he personally felt about them, the motives he represented – those of his government – were self-serving. While some believed the congress could attract foreign capital to Manchukuo, Japan’s primary aim was avoiding rupture with the United States. As historian Naoki Maruyama points out, this was Japan playing the “Jewish card”.

Jewish sources suggest that Higuchi was favorably disposed toward the local community and receptive to its pleas. Nonetheless, the general trend in Harbin was not in favor of the Jews and by 1940, initial visions of settling Manchukuo with Jewish refugees were abandoned. Evidently, the Harbin Jewish community was anxious about the Japanese regime, and its leader, Dr. Abraham Kaufman, did his utmost to appease and coax their decision makers, including Higuchi. Among other things, Kaufman registered Higuchi’s name in the Golden Book of the Jewish National Fund. This act did not require more than a monetary donation, as did thousands of Jews registering their sons or friends upon a family celebration. Kaufman for one never associated it with any act of “saving Jews” as is being currently touted.

Against this backdrop, it is striking that the largest gap in the legend of General Higuchi lies between the harsh reality of the Jewish community in Harbin and this rescue fantasy. This gap explains why historians ignored this over-dramatized and inflated anecdote during the first two decades after it appeared in 1971. So how did this minor and obscure affair, of a small number of refugees entering Manchukuo, turn into a major epic? How is it that many now refer to Higuchi as the “Japanese Schindler,” alluding to Oskar Schindler, the German businessman honored in Steven Spielberg's award-winning film for having saved the lives of 1,200 Jews during the Holocaust?

The current version of the Higuchi legend began when his grandson, retired musicology professor Ryuichi Higuchi, decided to salvage this story from oblivion. Nonetheless, the crucial turning point came somewhat later, when the late Hideaki Kase (1936–2022), a prolific diplomacy commentator and one of Japan’s leading historical revisionists, joined the fray. The two formed an association for the commemoration of Higuchi and brought the story to the media’s attention. The association quickly gathered many willing enthusiasts enchanted by the general’s goodwill. Kase also managed to recruit international backing by several American and Israeli Jews who were willing to lend support to the story, often without scrutinizing its credibility.

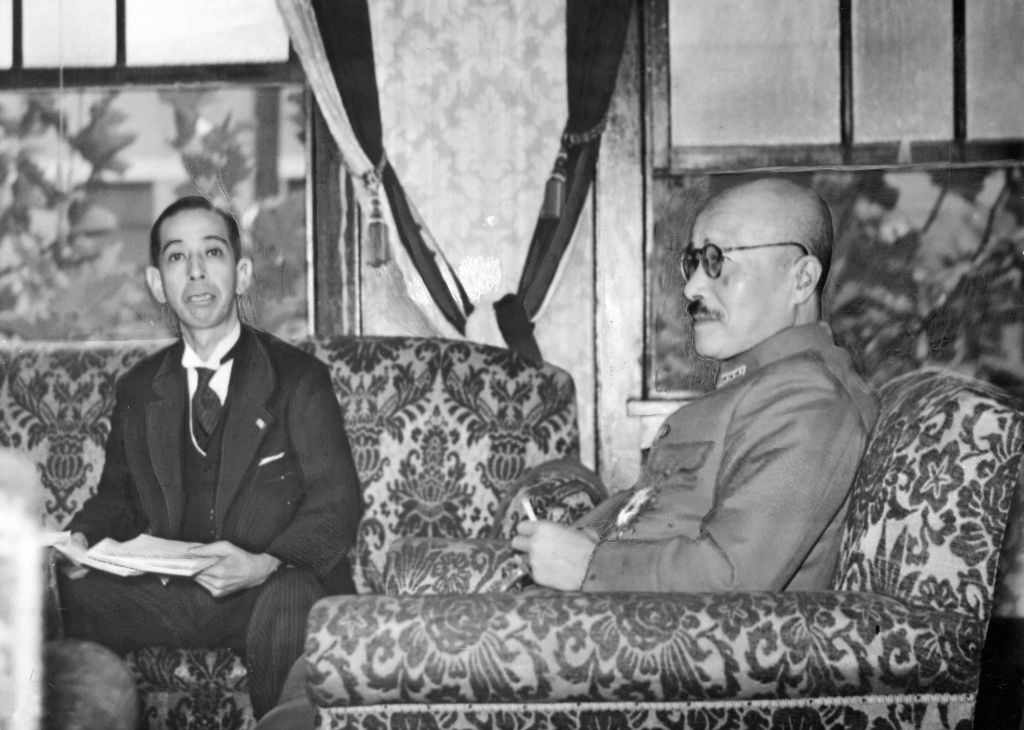

Photo by Mark Schreiber

The spectacular rise of this fable, however, cannot be understood merely as the product of a loyal grandson backed by an enthusiastic association. The social and cultural circumstances that made this story successful are broader. Indeed, since the 1990s, rightwing circles in Japan have been trying hard to improve the image of their country, both domestically and internationally, by revising its history. These efforts center on the nation’s conduct in Asia during the so-called Fifteen Years' War, referring to the period from the Mukden Incident of September 1931 through 1945.

The irony is that revisionists have resorted increasingly to involving Jews. Unlike Nazi Germany, current nationalist circles contend, Japan befriended them and strived to save them. Yet the historical reality is quite different. Apart from a few episodes of conscious humanitarian support alongside a tentative plan to utilize Jewish money and influence, wartime Japan did not extend help to the Jews trying to survive or find shelter in areas under its control. Rather, the opposite was the case. Although Japan did not exterminate these Jews, it impeded the passage of some, deported others, and eventually, during the last two years of the war, detained the majority of them simply for being Jews.

Kase was one of the leading figures in the efforts to revise the modern historiography of Japan. As head of the Society for the Dissemination of Historical Fact, as well as a member of other similar revisionist groups, he fought indefatigably to alter images that portray Imperial Japan as the bad guy in the Greater East Asia and Pacific War. He also considered himself a “friend of the Jews,” and so the Higuchi affair offered him a rare opportunity. Still, Kase for one was not interested in Higuchi per se since he was a too minor figure to rely on.

His holy grail was Hideki Tojo (1884–1948), Japan’s wartime prime minister and the main figure among the Japanese leadership tried and found guilty in the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal. As the Higuchi affair supposedly was happening, Tojo served as the chief of staff of the Kwantung Army – the unit that controlled Manchukuo. In the late 1990s, Kase was involved as a consultant in the production of the melodramatic film Pride: The Fateful Moment, which aimed to embellish Tojo's historical reputation. It is not surprising, then, that he elaborated now on Higuchi’s testimony that he did not act alone. It was Tojo, Kase insisted in an interview not long before his death, who made the ultimate decisions: “Higuchi took the initiative but Tojo approved.”

Tojo aside, the problem with Higuchi’s rise to fame is not merely a matter of insufficient sources or inflated figures, but the willful misuse of Jewish suffering. For many who hail this late general, putting him on a pedestal is tantamount to purging wartime Japan of its intense aggression and colonial heritage. In this sense, the recent emergence of Higuchi as a hero tells us much about contemporary Japan. The rise of ultra-nationalism and its moving into the mainstream during Shinzo Abe’s eight-year tenure may explain part of the success of this story. Nevertheless, the extensive use of the past to enhance the country’s soft power, and the capacity to exploit a dubious story without anyone casting skepticism over its claims, alert us to the vulnerability of truth to a determined assault.

Rotem Kowner is a historian and professor of Japanese Studies at the University of Haifa, Israel. His book Jewish Communities in Modern Asia (Cambridge University Press) is forthcoming.

Joshua Fogel is a historian and professor of East Asian history at York University, Toronto, Canada. He focuses historically on relations between China and Japan and has also written on the Jewish community in Harbin.