Issue:

April 2022 | Japan Media Watch

LDP hawks’ push for ‘discussion’ on nuclear sharing rings media alarm bells

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has revived interest among some Japanese politicians in the idea of sharing nuclear weapons with the United States. They claim that, almost 80 years after World War II, which ended with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan's policy of banning nuclear weapons from its soil has become a geopolitical anachronism. Proponents of nuclear sharing with Japan’s biggest ally say they simply want to "discuss" the matter, while Fumio Kishida, who as prime minister is also the president of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party [LDP], has stated he is against it.

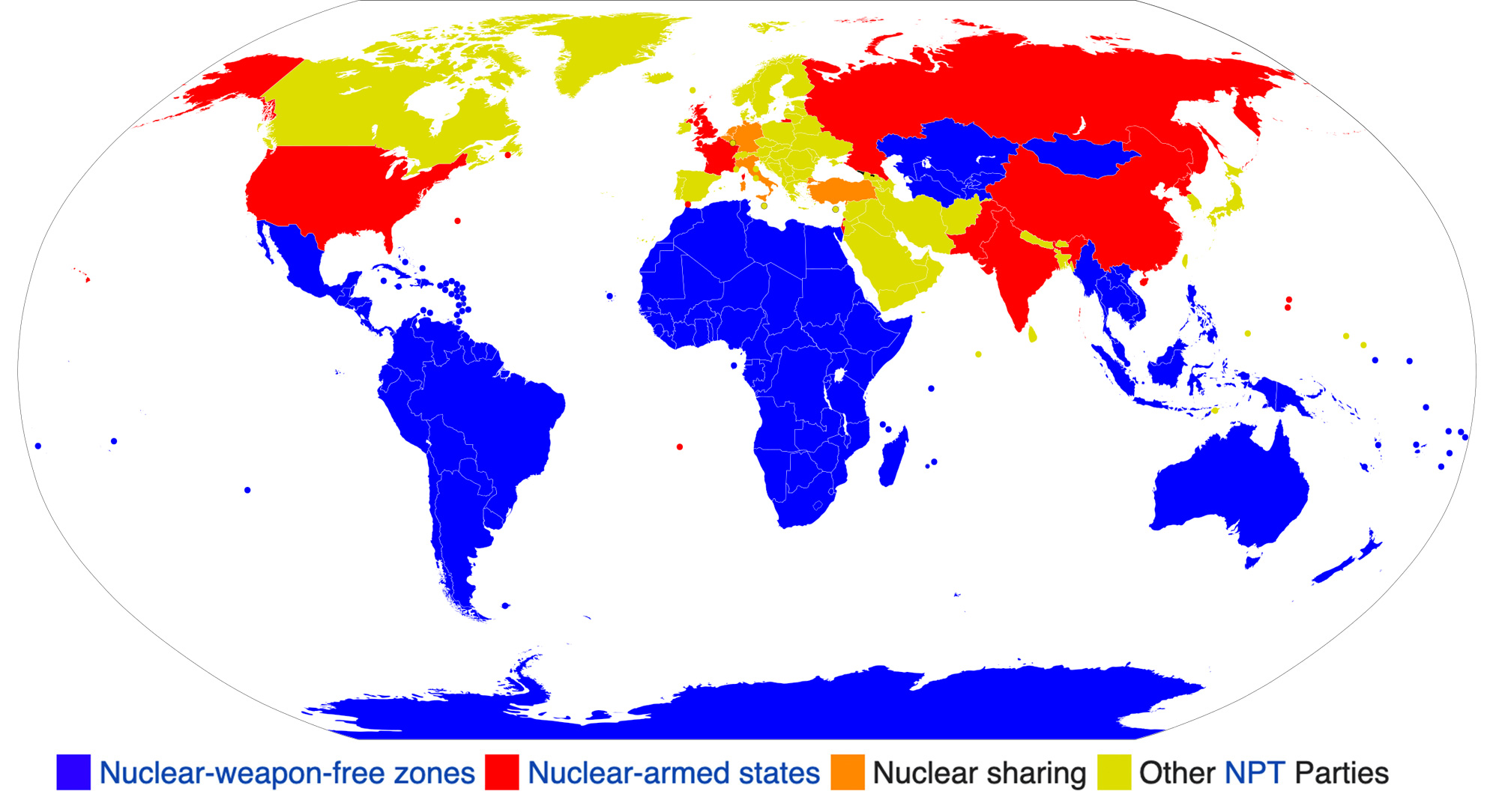

The concept of nuclear sharing, as exemplified by the North American Treaty Organization (NATO), allows for so-called non-nuclear states to "host" nuclear weapons provided by allied nuclear powers for the sake of collective security. According to Japan's "three non-nuclear principles," Japan will not possess, produce, or allow nuclear weapons within its borders. Though there have been indications over the years that these principles were violated by U.S. forces suspected of keeping nuclear weapons on vessels and facilities in Japan, the Japanese public generally supports these principles. The pro-sharing faction, led by former prime minister Shinzo Abe, has pointed to threats from China and North Korea, which have nuclear capabilities, as the main reason why Japan should share nuclear weapons with the U.S. as a form of deterrent. And now that Japan has condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – a conflict that could involve the use of nuclear weapons – this faction feels the matter is even more vital to Japanese security, especially given the backdrop of Japan’s own territorial dispute with Russia over the Northern Territories.

Abe mentioned the sharing concept during a discussion of Russia's invasion on a February 27 Fuji TV program. He said that nuclear weapons should be discussed as an "option" for defending Japan. Shortly thereafter, Kishida rejected the suggestion, citing not only the three non-nuclear principles but also the Atomic Energy Basic Law, which states that Japan will only use nuclear technology for "peaceful purposes." However, other LDP lawmakers, in particular former cabinet minister and close Abe ally Sanae Takaichi, have reinforced the drive for discussion, gaining extensive media coverage in the process. More significantly, Ichiro Matsui, the mayor of Osaka and leader of the opposition Nippon Ishin no Kai (Japan Innovation Party) has also called for a discussion about sharing, dismissing the non-nuclear principles as belonging to a "bygone era," according to The Asahi Shimbun. Cited on the media watchdog website Litera, nuclear policy researcher Masaru Murano pointed out that nuclear sharing as defined by NATO was a relic of the Cold War, and thus the deterrent rationale for having or sharing nuclear weapons no longer holds. Under the "first-strike capability" scenario that has dominated debate since the fall of the Soviet Union - a capability the pro-sharing element supports to an extent – if Japan has nuclear weapons it is more likely to come under nuclear attack.

Matsui's support for sharing has been scrutinized for another reason. Former LDP lawmaker Muneo Suzuki, now an Ishin member whose connections to Russia goes way back to his old Hokkaido constituency – and which has propelled him into a central role in the Northern Territories dispute - has questioned Ukraine's victim narrative. Though Suzuki has criticized the invasion, he claims that Ukraine is partly to blame since it has not upheld its end of the Minsk Agreement, which was signed in 2014 to end the conflict in two Russia-affiliated regions of Ukraine. Subsequently, Suzuki has defended Russian actions in Japan's parliament. Litera reported that the Ukrainian ambassador to Japan called Suzuki's remarks "disgusting," but Ishin has not responded, thus prompting Litera to speculate that Ishin has become a de facto "ally" of Russia in Japan. Toru Hashimoto, often credited for creating Ishin, has also said publicly that NATO should reach some sort of compromise with Russian President Vladimir Putin, although he has since come around to Ukraine’s cause.

Moreover, in the past, Ishin's attitude toward Japan's nuclear power capabilities held that reactors should be phased out over time, according to The Mainichi Shimbun. Now, however, Ishin is calling for nuclear power plants to resume operations to ensure a stable supply of energy, a change of heart spurred by the possible disruption of oil and natural gas supplies caused by Russia's actions. But there are other factors that could be in play as well. Japan's nuclear reactors produce weapons-grade plutonium, and while Japanese law prevents these materials from being converted for such purposes, the possibility is always there. In effect, Japan could easily and quickly become a nuclear power itself, though it would require a sea change in the national mood, as well as the assent of the U.S. While Washington promoted nuclear energy in Japan, it has always been cautious about Japan as a nuclear power, believing it would destabilize the entire region.

Consequently, the combined push to discuss sharing and restart more nuclear reactors has rung alarm bells in certain sections of the media, for much the same reason that Murano stated. Even if Japan does not share nuclear weapons or produce its own, the reactors can become targets in a war. Dr. Karly Burch of New Zealand's University of Otago recently wrote that it was wrong to call Ukraine a "non-nuclear state" just because it has no nuclear weapons. It has nuclear power plants, and following the Russian invasion, the world held its collective breath when it was feared that Russian forces would attack the plants or otherwise disrupt their operations, either of which could lead to deadly releases of radiation. In other words, nuclear reactors can be used as weapons against the very people they serve.

Following the triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in March 2011, Japan shut down all of its atomic plants, with the intention of restarting them after the introduction of stricter safety and security measures. Since then, only a handful have gone back online, and some were prevented from doing so by courts that judged these measures had not been fully implemented. In 2021, it was reported that security lapses had led to unauthorized personnel entering the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear plant in Niigata Prefecture, the largest in the world. During a 2015 discussion in the Diet, opposition lawmaker Taro Yamamoto asked then prime minister, Shinzo Abe, if Japan's nuclear power stations were strong enough to withstand a missile attack. Abe was unable to give him a definite answer.

Litera made a similar point in a March 10 article that cited a 2011 Asahi Shimbun scoop about a 63-page 1984 report commissioned by the Japanese government which concluded that an attack on the Fukushima Daiichi plant could result in the "immediate" deaths of up to 18,000 nearby residents from radiation exposure. The government did not make the report public or incorporate its findings into its nuclear power policy, fearing pushback from Japan’s anti-nuclear movement. As former Asahi Shimbun reporter Hiroshi Samejima wrote on his blog, the possibility of such an attack is hardly insignificant considering that Japan has "dozens" of reactors throughout the archipelago, but mainly on the Sea of Japan, facing its traditional enemies. The fact that the media have not addressed this aspect when “discussing” the nuclear sharing issue, he suggests, is irresponsible.

Sources

Drop the Taboo, Talk About Japan Developing Nuclear Weapons

https://samejimahiroshi.com/politics-nuclear-20220306/

https://samejimahiroshi.com/politics-nuclear-20220304/

https://www.taro-yamamoto.jp/english/5023

Japan’s regulator finds massive security breaches at Tepco’s Kashiwazaki-Kariwa NPP

Philip Brasor is a Tokyo-based writer who covers entertainment, the Japanese media, and money issues. He writes the Japan Media Watch column for The Number 1 Shimbun.