Issue:

April 2022

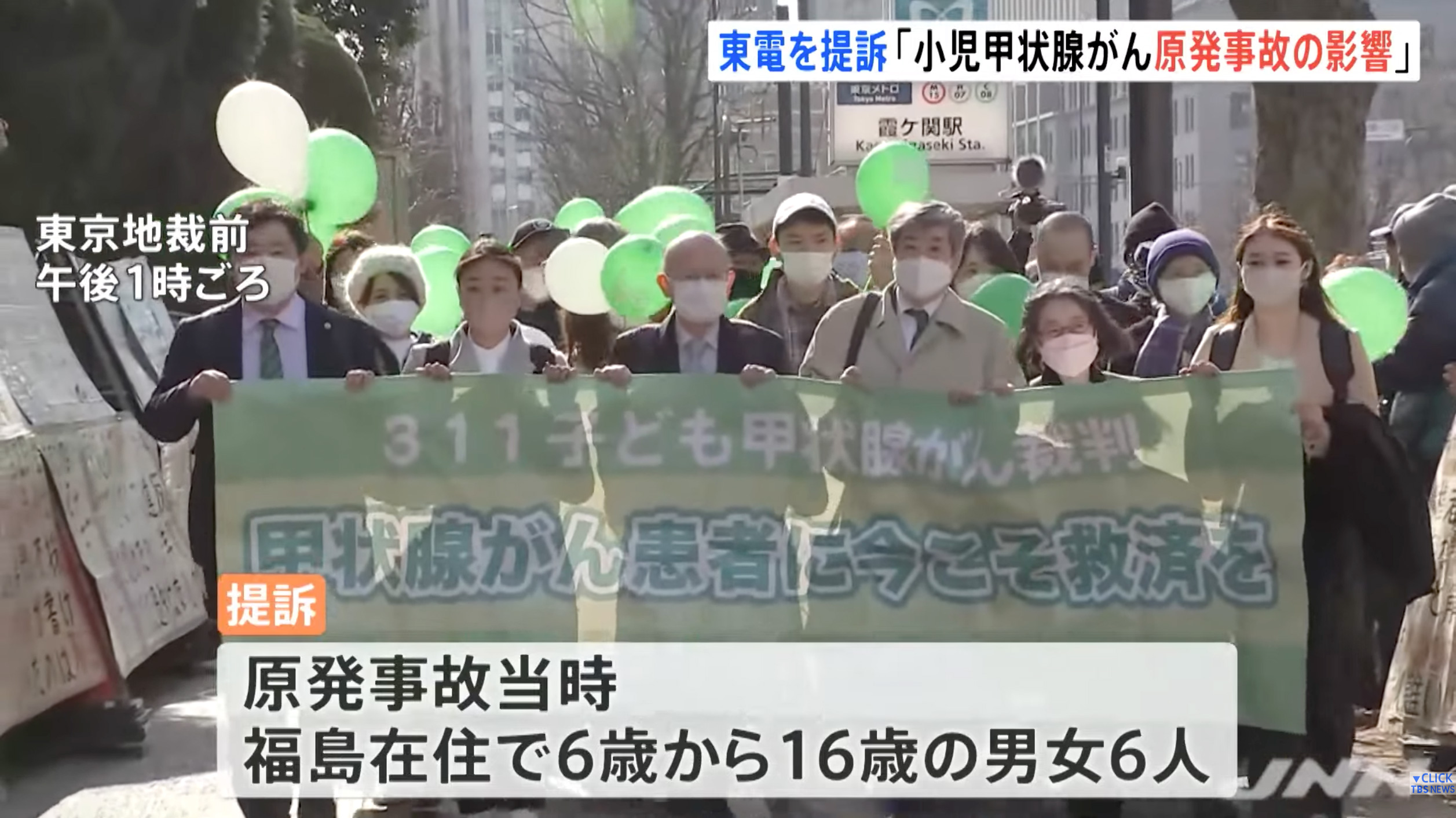

Thyroid cancer survivors take their fight for recognition to court, 11 years after the meltdown

Six people from Fukushima Prefecture who were aged between six and 16 at the time of the March 2011 nuclear disaster are seeking justice and damages after contracting a rare childhood cancer they claim is linked to radiation exposure.

Speaking at a news conference at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan on the 11th anniversary of the Fukushima disaster last month, attorneys Kenichi Ido and Hiroyuki Kawai of the 3.11 Children’s Thyroid Cancer Lawsuit said: “There is no reason to assume that after an accident of such scale there would be no health risk to the population.”

The alliance was formed by nearly 300 people who have been diagnosed with thyroid cancer since the triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, operated by Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), following a powerful earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011.

In a written statement issued before the press conference, the six plaintiffs, now aged 17-27, described the shock they felt when first diagnosed with pediatric papillary carcinoma, a rare childhood cancer of the thyroid, and the health problems they have experienced for more than a decade.

Of the six, two have undergone a lobectomy (the entire removal of one lung), while four have had their thyroids removed, forcing them to take artificial hormones for the rest of their lives and placing an additional burden on their family finances.

One of the plaintiffs who had surgery was Aoi, a 26-year-old woman who was a junior high school student at the time of the accident. Aoi, who did not want to give her family name for fear of reprisals, said: “I’m worried about the future. I can’t think of anything like marriage or childbirth.”

Some victims have undergone intensive Radioactive Iodine (RAI) therapy since they were diagnosed as children and have been unable to complete their university education or start work.

The plaintiffs claim a there was a causal relationship between their diagnoses and their exposure to radiation in Fukushima. Naturally occurring paediatric thyroid cancer is very rare, affecting one to two children per million, according to the Lancet medical journal. At the last count, about 293 Fukushima children under the age of 18 out of a total of nearly 360,000 children who were screened for thyroid issues at least once in the aftermath of the disaster were diagnosed with the condition.

This figure is “dozens of times higher than the national figure,” according to Ida. Wearing a green bowtie in the shape of a thyroid gland, he accused the Japanese government of downplaying the possible health risks from exposure to nuclear fallout and of claiming instead that the unusual high number of cases is the result of over-diagnosis.

Experts are divided over the cause of thyroid cancer cases in Fukushima children.

Shoichiro Tsugane, head of the Research Center for Cancer Prevention and Screening at the National Cancer Center and a member of the Fukushima prefectural government's expert panel, and another team headed by Okayama University Professor Toshihide Tsuda, published papers on the subject in January 2016 and October 2015, respectively.

According to The Mainichi Shimbun, both papers were based on the first round of screening conducted between 2011 and 2015.

Of the 300,000 children screened at the time of their analysis, thyroid cancer was detected in 113 subjects, including suspected cases. Although their calculation methods differ, the two teams both concluded that the occurrence was “about 30 times” that of national levels. But they disagree over the cause.

Drawing on similar thyroid screenings conducted among adults in South Korea in the late 1990s, Tsugane, whose research forms the basis for government claims of over-diagnosis, argued that the maximum radiation exposure in the thyroids of children in Fukushima Prefecture, which is estimated at several dozen millisieverts, was not sufficient to cause a 30-fold increase in the number of patients.

Tsugane argued that there was no evidence showing that the number of patients rises in areas with high radiation levels. Tsuda’s research, however, took into account differences in the timing of screenings among children and found cases in Futaba, located close to Fukushima Daiichi, were 4.6 times higher than in Sukagawa and other areas located further from the plant.

Based on his findings, Tsuda concluded that radiation exposure was the main cause of the high prevalence of cancer in children.

The plaintiffs are demanding a total of ¥660 million (around $5.3 million) from Tepco for the hardship they have experienced and expect to encounter in the future. Ido and Kawai said their clients were seeking the same recognition and lifelong care offered to hibakusha survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Kawai insisted that there was more at stake than monetary compensation. He urged the public to understand that the decision to file the lawsuit had not been taken lightly. “There is an enormous pressure to stay silent about these issues," he said.

Speaking out is inconvenient for Fukushima, as it fuels harmful rumors that will impact the region’s recovery,” Kawai added. “Often, the patient and the mother are the only two people who know about the diagnosis. Even the fathers and siblings don’t know.”

Ilgın Yorulmaz is a reporter for BBC World Turkish. She is the Second Vice President of FCCJ and also serves on its Diversity Committee.