Issue:

June 2024

A journey on foot into feudal criminal justice and the tough love of Hasegawa Heizo

Rather than battle the crowds during the Golden Week holidays, I decided to put the time to good use updating and expanding my photo library. That meant returning to the scenes of the crimes that I'd photographed back in the days when I used prints from 35mm color film, and later old, low-resolution jpegs.

Once again, I was reminded of the impermanence of all things. Photos I'd taken around the city decades ago, while working on the first of my two nonfiction crime histories (published in 1996 and 2001), were of places or objects that no longer exist, such as the old wood building near Shiinamachi station in Toshima Ward that formerly housed the Teikoku Bank and was the site of an enigmatic murder-robbery in January 1948. Or a plaque mounted on the small bridge at Nakanohashi, Minato Ward, marking the spot where Henry Heusken, Dutch interpreter to U.S. counsel general Townsend Harris, sustained fatal wounds at the hands of xenophobic samurai on the evening of January 15, 1861. For these, all I could do was retouch my old color prints using Adobe Photoshop.

I've also been adding photos of other historical locales as I track them down online. On April 28, I headed for Yotsuya Sanchome on the Marunouchi subway line, where the educational Fire Museum [https://www.tfd.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/eng/e_museum.html], located directly above the station, can be visited free of charge.

En route to my destination is the Oiwa Inari Tamiya shrine, dedicated to Oiwa, who according to popular legend was said to have been murdered by her husband to gain her inheritance, and whose spirit returned to wreak terrible vengeance, driving him to madness. The tale was featured in Tsuruya Namboku's famous 1825 Kabuki drama, Tokaido Yotsuya Kaidan, and has been subject of some 30 horror films.

Near the two Oiwa shrines and about midway between Yotsuya Sanchome and Shinanomachi on the JR Sobu line, I turned left off Gaien Higashi Dori and walked for about five minutes to Kaigyozaka slope. An immediate left through the gate at 9-3 Suga-cho took me to the well-tended grounds of Kaigyo-ji temple, which boasts both an attractive monument and the grave of Hasegawa Heizo.

Born Hasegawa Nobutame, he served as tozoku hitsuke aratamekata (official in charge of dealing with brigands and arsonists), heading Edo's version of the serious crimes unit from 1787 until his death in 1795 at age 51.

In the late 18th century, famine in the countryside drove thousands of desperate people to Edo, and the growing number of destitute people posed serious problems for law enforcement officials, keeping Hasegawa's unit busy and earning him the sobriquet Onihei (Hei the Demon) among the criminals he brought to justice.

In addition to his policing duties, Hasegawa spent his final years overseeing a juvenile reform facility called the ninsoku yoseba.

Matsudaira Sadanobu, a member of the governing council of elders, who was effectively the country’s administrative ruler, had first proposed transporting Edo's excess criminals to Tohoku, where they could be put to work clearing land for farming. This idea, however, met with strong opposition from the local lords.

Matsudaira's solution was to create the ninsoku yoseba, located on a triangular strip of reclaimed land between the islands of Ishikawajima and Tsukudajima, close to where the Sumida River flows into Tokyo Bay.

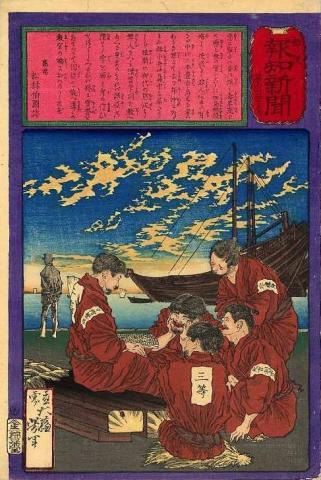

Here, under Hasegawa's overall supervision, several hundred prisoners between the ages of 14 to 20 were taught skills that ran the gamut of everything from carpentry, shoemaking, blacksmithing, stonemasonry, charcoal- and paper-making and hair grooming to the carving of false teeth. Wages were paid every 10 days, but one-third of earnings were held back and given to prisoners in a lump sum upon their release, typically after three or more years.

Inmates worked from around 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. They were allowed three days off per month and had hot water for bathing every other day. They also had access to medical care. Women worked in the kitchens, where, in addition to preparing regular meals, they served up special dishes at the New Year and on other holidays.

Even more to the credit of its operators, the facility did not drain the government’s coffers, and may have actually turned a profit. Trustee prisoners, recognizable by their distinctive happi coats, could be seen in the city's markets selling lamp oil and other products. Additional revenues were earned from leasing part of its land to store building materials.

While life on the island was regimented and punishments could be harsh, treatment was reasonably humane, and Japan can take pride in the fact that it was one of the first countries in the world to rehabilitate lawbreakers through vocational training.

The functions of ninsoku yoseba ended in 1870 and the facility was utilized as a conventional prison until its transfer to Sugamo, Toshima Ward, in 1895.

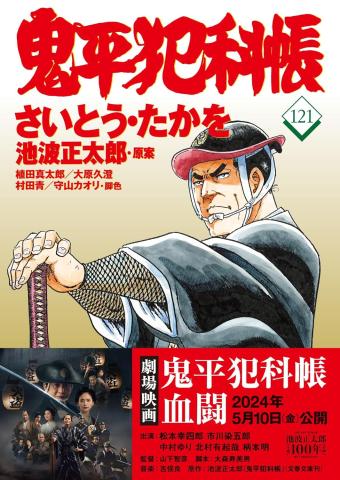

That Hasegawa's career remains widely known today can be credited to Onihei Hankacho (Casebook of Hei the Demon), novels and short stories penned by prolific author Shotaro Ikenami (1923-1990). Starting from black-and-white TV dramas on TV Asahi in 1969, several performers portrayed Hasegawa in the title role, the most long-running of which was kabuki actor Nakamura Kichiemon II, who held the role from 1989 to 2016.

A key factor in the success of the TV dramas was said to be their historical authenticity.

"Onihei Hankacho was very faithful to detail," Yumio Nawa, an authority on Japan’s feudal law enforcement and advisor to many period dramas, said in a 2001 interview with Japan Quarterly magazine. "The show had the advantage of the best writer, best actors – especially Nakamura Kichiemon – and best producer, in Hisao Ichikawa."

According to Kaoru Kojima, an editor at Kodansha who worked closely with Ikenami until his death, Onihei was characterized as possessing both severity and human sentiment, being highly skilled in mixing criticism with praise to get people to conform to his wishes.

"He punishes evil deeds, yet saves people when possible, for example by recruiting a lawbreaker into becoming his informer – as was actually done in those times," Kojima said. "Ikenami’s pursuit was not only to present historical facts; his major focus concerned the individual man, through relationships and conflicts within organizations."

In this regard, Kojima viewed Ikenami’s stories as analogous to the Japanese board game of shogi, whose rules, unlike Western chess, permit pieces removed from the board to be restored. In the same manner, Onihei persuades or manipulates people into leading useful lives.

"Younger generation Japanese fans of Onihei are able to feel a sense of relief, along with the desire to have a person with Hasegawa's attributes as their father, husband, brother or boss," Kojima said.

Mark Schreiber is author of Shocking Crimes of Postwar Japan (Yenbooks, 1996) and The Dark Side: Infamous Japanese Crimes and Criminals (Kodansha International, 2001).