Issue:

After overseeing the secrecy bill’s passage through the Diet, a long-time Abe ally comes to the FCCJ to defend the content of the new law

Does the recent introduction of the designated law spell the end of Shinzo Abe’s honeymoon period?

Having given him a relatively easy ride since he took office a year ago, Japan’s media and public have turned on the prime minister. After the secrets bill became law in early December, Abe’s approval ratings sank to below 50 percent; concern over the controversial legislation even united the country’s editorial writers.

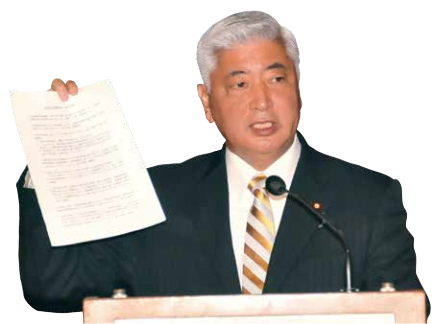

The unenviable task of selling the law to journalists fell to Gen Nakatani, a lower-house member of the Liberal Democratic Party and longtime Abe ally who was instrumental in the launch of Japan’s U.S.-style National Security Council (NSC) and overseeing the secrecy law’s stormy passage through the Diet.

“When it comes to state secrets, I seem to have a destiny that is closely intertwined with the state secrets bill and the NSC, and a strong sense of responsibility for their introduction,” Nakatani said during an appearance at the Club.

Under the new law, public officials and private citizens who leak information designated as a special state secret face prison terms of up to 10 years, while journalists who seek to obtain the classified information could get up to five years.

The law was passed amid noisy demonstrations and opposition from journalists, lawyers, politicians, academics, scientists, even film directors and manga artists. Critics say the prospect of prison terms will deter whistleblowers, while journalists face jail time simply for trying to do their job. There is concern, too, that the law’s vague definition of what constitutes a state secret will give officials carte blanche to keep sensitive or embarrassing information out of the public domain.

Nakatani, however, attempted to frame the law as a purely administrative measure designed to promote information sharing among officials and end the silo mentality found among government agencies. “Until now we didn’t have a government organization that could protect government secrets . . . each ministry and agency could designate certain information as secret, but there was no coordination,” he said. “This is the first time we’ve had a law that covers all agencies and ministries. This is a good step forward.”

Nakatani said the law and the NSC would, for the first time, enable officials to discuss information and make recommendations to the prime minister, as well as more easily obtain information from the U.S. and other allies. “That’s why it is important that we have a framework that will ensure there are no leaks,” he said.

Nakatani acknowledged widespread concern that the law will impinge on the public’s right to know. In response, he said the government had made a dozen changes to the draft bill to reflect the concerns of other parties in the Diet, including tightening the definition of what constitutes a state secret, an agreement to declassify all but a few secrets after a maximum of 30 years and an assurance that ordinary citizens, including journalists, will not be penalized.

“I know there is a great deal of concern among many people about the secrecy law and whether there might be some possible violation of the public’s right to know,” he said. “But I would like to reassure you that in regard to the behavior of the average person, the penalties really do not apply to them. If a person eventually learns about secrets, and if this is within the con-fines of ordinary behavior pat-terns, they cannot be penalized. The secrecy law does not in any way violate a person’s right to know.”

Japan’s newspapers joined forces to oppose the bill. They are unconvinced by official assurances that newsgathering activities will not be affected, particularly after the justice minister, Sadakazu Tanigaki, refused to rule out raids on media organizations suspected of breaking the law. In addition, Masako Mori, the state minister in charge of the bill, said the law could be applied to Japan’s nuclear power industry a potential target for terrorists. Nakatani was asked about a theoretical incident involving Japan and China in the East China Sea that had been deemed secret by a government agency. Would a journalist who obtained information about the incident from a bureaucrat be penalized?

His answer said a lot about the nebulous wording of the law. He cited Article 24, which states that a person will be subject to penalties of up to 10 years in prison only if he is working on behalf of another nation, is seeking to benefit personally from the leak, or behaves in a way that impairs the safety of Japan and its citizens.

“Ordinary news gathering by the media is not subject to penalties,” he said. “Journalists and other ordinary citizens do not know which matters are state secrets, so even if they ask about these matters, they are not subjected to penalties. The law says very clearly that penalties only apply if someone is trying to get information on behalf of a foreign government, or is involved in espionage or terrorist activities.”

So much for the supposed safeguards against arrest for obtaining secret information. What if the journalist involved were also to report it? “If one obtains secret information and broadcasts or writes about it without knowing that it’s been designated a state secret, then the journalist or media organization would not be penalized,” Nakatani said.

He added: “If journalists disclose information as part of spy activities or helping terrorism with the intention of damaging the national interests of Japan, then that might be different. But without that motivation, there would be no penalty.”

Justin McCurry is Japan and Korea correspondent for the Guardian and the Observer. He contributes to the Christian Science Monitor and the Lancet medical journal, and reports on Japan and Korea for France 24 TV.