Issue:

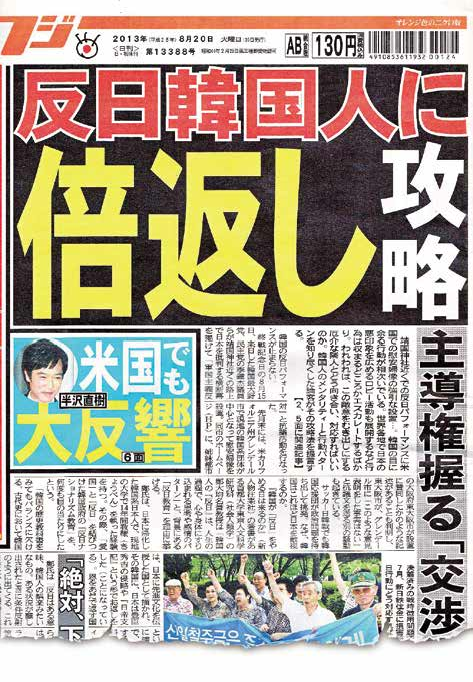

The afternoon tabloid Yukan Fuji is on a mission with an anti-South Korean series of headlines that clamor for attention

One of Japan’s four top buzzwords for 2013, announced at a gala event in Tokyo on Dec. 2, was Bai-gaeshi (literally “double payback”). The phrase was popularized in last summer’s TBS TV drama, “Hanzawa Naoki,” the tale of an honest young banker struggling against his venal superiors. At the conclusion of the episodes Hanzawa would blurt out “Baigaeshi!” vowing to extract vengeance on his tormenters, as it were, in spades. In the course of the drama’s run, the scale of revenge exponentially inflated to jubai-gaeshi (10-fold pay-back) and then hyakubai-gaeshi (100-fold payback).

Bai-gaeshi and its incre-mental variants also describe the self-prescribed mission of the afternoon newspaper Yukan Fuji in its reportage on South Korea during much of 2013. On several occasions, the term has even been used in that context in the tabloid’s own front-page headlines.

But you can pick any headline at random like Oct. 19’s “Kankoku akireta hannichi jisatsu koi,” (“South Korea’s idiotic anti-Japanese suicidal acts”) and get the inescapable message. The tabloid’s bright orange, 72-point characters are hard to miss, both in the newspaper itself, or on the elongated paper strips hung out to promote each day’s edition on the low racks ringing rail station kiosks and in convenience stores.

The volume and frequency of Yukan Fuji’s negative articles on South Korea began to soar from last spring and gathered momentum over the summer. By October, at least 20 of 26 front pages (there’s no edition on Sundays) featured headlines portraying the ROK in a negative light in many instances at the exclusion of virtually all other news topics.

Instead of varying its international news with the usual mixture of domestic politics, scandals, showbiz gossip and sports, Yukan Fuji has largely restricted its menu to a veritable alphabet soup of anti-Korean barbs. They ranged from A, (“ad hominem” attacks on Korea’s president Park Guen-hye and her late father Park Chung-hee); and B (the high incidence of cosmetic surgery among Korean “beauty contest winners”); to C (the “comfort women” issue); D (the territorial dispute over “Dokdo” aka Takeshima island); H (the collapse of the so-called “Hanryu wave” of Korean popular culture); I (Koreans being “ingrates” for not acknowledging that Japan brought about their modernization from a semi-feudal, primitive economy); P (tens of thousands of Korean “prostitutes” plying their trade in Japan); and S (a recent bout-fixing scandal in “ssireum,” Korea’s native sumo).

THE OVERALL TONE OF SUCH REPORTAGE HAS NOT ONLY INCREASED, BUT BECOME INCREASINGLY MEAN-SPIRITED AND ABUSIVE

Then there’s U, from the word urijinaru, a composite of uri, the Korean word for “our,” and “original,” as is applied to things that Koreans claim they were first to accomplish. These include origami, kendo (Japanese stick fencing), enka (Japanese traditional ballads), the magnetic compass, pizza (“stolen by Marco Polo”), the airplane and soccer.

Imagine how absurd it would seem if Japanese claimed they had, for example, invented kimchi. Yet to make its point, an article in the January issue of the monthly Sapio magazine which was bashing Korea years before the Yukan Fuji’s current screed attempts to do just that, citing a 17th-century Korean document reporting to the effect that red peppers were first imported into Korea via Japan.

How did this disquieting situation come to pass? At the risk of oversimplification, the Japanese reaction could be ascribed as a response to two recent trends. First, in Yukan Fuji’s own words, (from its Dec. 10 edition), the two countries’ relations began to deteriorate just two weeks after Park Guen-hye’s election as president, when the ROK (and China) absented themselves from a memorial ceremony on March 11, the second anniversary of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami. Korea claimed non-attendance due to an “office miscommunication.”

Despite visits to the U.S., China and other countries, and attendance at the G20 meeting, Korea’s president-elect made no effort to connect with her Japanese counterpart. (In fact, the Korea Joongang Daily coined the word “isolation diplomacy” to describe Park’s new policy.) And during a visit to Seoul in September, U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel was subjected to an “exclusive anti-Japanese tirade.”

The second phenomena was an increasingly shrill wave of often crude assaults on Japan and its institutions by Korean groups or individuals that took place in the U.S., Europe, and Asia (including Japan) such as the aborted arson attempt by a Korean national at the Yasukuni Shrine, and the threats to boycott the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, which were collectively described in the Shukan Post as “anti-Japanese harassment.”

Interestingly, while the “hate speech” that’s been regurgitated during street demonstrations by right-wing organizations in Shin-Okubo and other Korean enclaves in Japan attracted considerable media coverage and parliamentary debate in Japan, scant space has been devoted to analysis of the new anti-Korean slant that’s been spreading through Japan’s print media, both tabloid newspapers and magazines.

One exception, which appeared in Tokyo Shimbun on Oct. 5, attempted to disparage Yukan Fuji’s articles, suggesting many of the tabloid’s inflammatory headlines were a case of Yoto-kuniku (a Chinese aphorism translated as “displaying a sheep’s head and selling dog meat”), with the text of the articles failing to deliver on the headlines’ promises.

Frequent reports to the effect that Korea’s economy is on the verge of collapse were largely contradicted by a report from Goldman Sachs, which in a Portfolio Strategy Research report dated Oct. 11 upgraded its GDP forecasts for Korea. And while Yukan Fuji regularly described Pres. Park as being a diplomatic disaster for Korea, this appears to be contradicted by local reportage.

Tom Coyner, president of Korea-based Soft Landing Consulting, a sales consulting firm, says that Park is generally given her highest marks in diplomacy, “particularly when it comes to handling North Korea, presenting South Korea in a positive light in Europe and the U.S., and how she is taking a strong stand vis-à-vis Japan.”

Yukan Fuji’s heavy-handed reporting may or may not be perceived by other Japanese publications, particularly the weekly magazines, as the green light for them to leap into the fray. One thing for sure, however, is that the overall tone of such reportage has not only increased, but become increasingly mean-spirited and abusive.

Near the fundament of the media food chain are scurrilous publications such as Jitsuwa Bunka Tabuu, a monthly from Coremagazine Co. Inc. (which last August was identified as the source of the tall tale on eyeball-licking among primary schoolers that went viral on the internet). Recent issues of Jitsuwa Bunka Tabuu now include a column titled “Kankoku Baka News” (“Stupid news from Korea”), with each Japanese headline purposely ended using nida, the Korean form of the copula.

As media restraints fall off, even more respectable magazines now appear to be wading in with gusto. Shukan Shincho (Nov. 28) ran a three-page story titled “The father of president Park was a manager of ‘comfort women for the U.S. military!’ “The article cited a report on Korean women who worked at “prostitution villages” adjacent to U.S. bases, and claimed to reveal a document bearing the signature of S. Korea’s late president Park Chung Hee, father of the current president.

The article went on to criticize Koreans for maintaining a “double standard” on the comfort women issue.

Needless to say, the tsunami of negative reporting threatens to drown out efforts to convey positive news from either side. “Actually,” Soft Landing’s Coyner observed, “when it comes to tourism, fashion trends and technology, one can often read positive things in the Korean press about Japan. The average Korean tends to have a generally favorable or at least, not decidedly negative feelings about Japan, so long as historical and political matters are not discussed or considered.”

A former Kyodo journalist who sifted through a stack of back issues of Yukan Fuji, said of the hardline stance: “If you ask me, I think the Sankei Shimbun [Yukan Fuji’s parent paper] is doing this to please Prime Minister Abe, and gain favor among the LDP.” And an editor at one of the national dailies said he believes Yukan Fuji’s stance is no more than a cynical move aimed at boosting circulation by pandering to readers who get a vicarious lift from the daily bashing session.

A staff member of Yukan Fuji who agreed to discuss his company’s editorial stance toward Korea, was unapologetic. The current editorial tone, he said, was fully justified, with his newspaper’s approach tailored to address readers’ heightened concerns.

He did not dismiss out-of-hand the view that the chill in bilateral relations coincided with the end of the “honeymoon” for Korea’s new president, when Japanese realized to their disappointment that Park appeared disinclined to undo the ill will stoked by her predecessor, Lee Myung-bak. “When and if the tensions subside, then we’ll reconsider toning down the rhetoric,” he said.

As long as the widespread view persists that Koreans are determined to engage in what Japanese perceive as petty harassment, readers may continue to seek catharsis in the bai-gaeshi formula. The question still remains, though: will the invective boil over into something even more toxic that neither Koreans nor Japanese really want?

Mark Schreiber currently writes the “Big in Japan” and “Bilingual” columns for the Japan Times. He dismembered the global eyeball-licking media phenomena in our August, 2013 issue.