Issue:

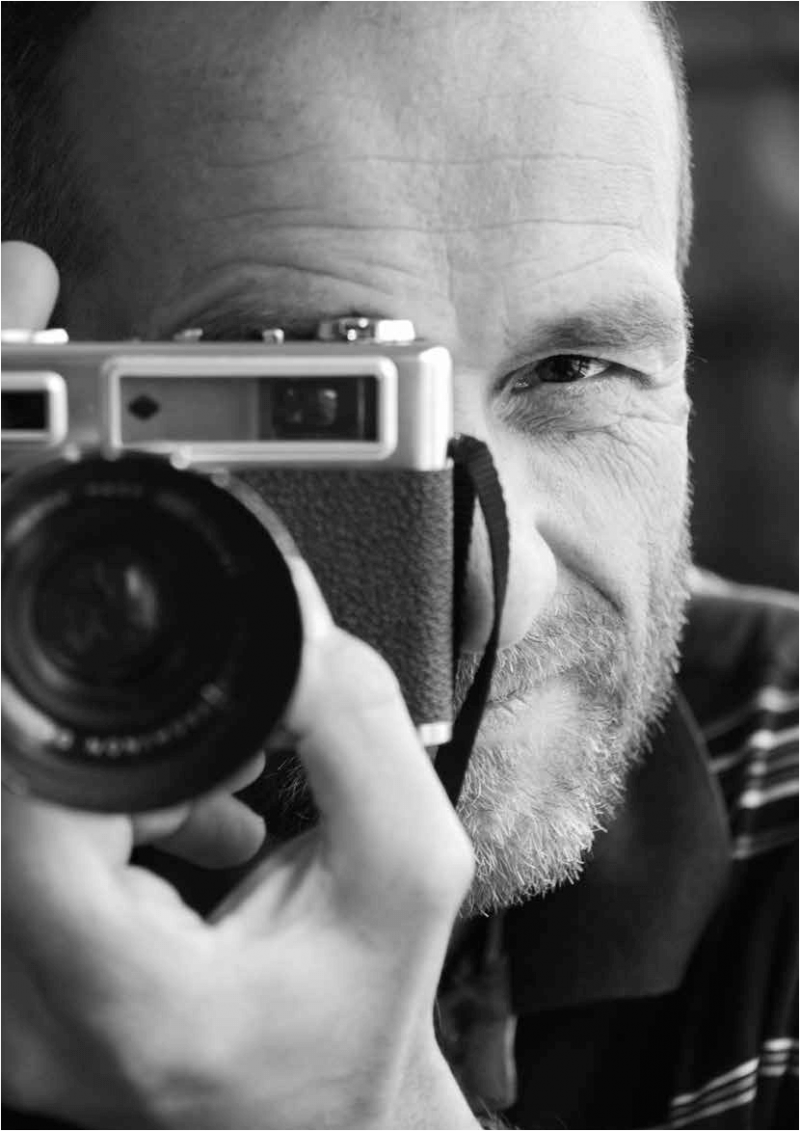

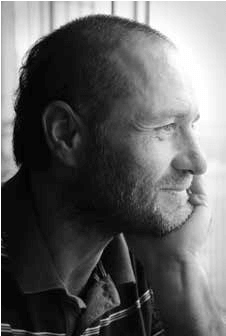

Martin Hladik

by ANDREW POTHECARY

The “undergound” tattoo scene was similar to the “underground,” away from prying state powers, that he’d known in his youth

Martin Hladik was born in Czechoslovakia in 1968, only a few months before the “Prague Spring” reformist movement was crushed under the tread of Soviet tanks. So when he grew up, it was under the restrictions of movement and thought of Soviet rule.

His father was a mechanical engineer and his mother produced exhibitions middle class work that brought enough money only for everyday life. Even getting permission for travel was difficult. The family once managed a trip to Yugoslavia, but only had enough money for gas and camp. Hladik’s mother prepared all food for the month’s trip in advance for the family of four.

He studied Mechanical Engineering at the Czech Technical University in Prague “a way to avoid army service” and spent a further two years taking selected classes in photography at the Academy of Performing Arts.

Like other Sovietbloc nations, the state gave support to sport, and throughout his youth, weekend trips to the mountains for winter skiing and summer kayaking had led to Hladik joining sports clubs. After university, he turned to his sport full time and in 1995 joined the national whitewater slalom team following the end of communist rule.

His love for photography, however which had dated from his childhood eventually led him to put his kayak aside for a camera. He knew the work of the exiled Joseph Koudelka, since prints of his photographs of the 1968 Soviet invasion had been illicitly available. He also had seen the work of Cartier Bresson, Robert Capa and Douglas Duncan the latter two known for their war photography.

Hladik was approaching 30 when he set off for New York to find work as a photographer. He had no accommodation, little English and barely enough money to buy food. He was arrested for sleeping in the park. A wedding photographer hired him, but fired him the same day after Hladik, in his hunger, couldn’t stop himself from eating the wedding food. But he got to assist the renowned Czech born American photographer Antonin Kratochvil with his portraiture.

After returning home, he began his career as a photographer in earnest. With his girlfriend and brother he made a six month bike trip around the eastern Mediterranean for a Czech motorbike firm’s PR and found work on movie productions. When the Catholic charity Caritas asked him to work with them in wartorn Kosovo in 1999, the reality on the ground changed his perspective of war photography, and brought him to the realization that he was looking to shoot people in happier situations.

In 2000, he followed his Czech girl M friend to Japan after she got a scholarship for a PhD at Tokyo University, where she still works in water related engineering. They have since married and have three children, aged 9, 6 and 4.

Hladik had visited Japan in 1995 as a kayaker, but had never thought of returning. To make a career here, he would have to build up contacts and introductions from scratch. It’s been a long road. “I’m not there yet,” he says. “It’s still difficult. The best time was until the financial crisis in 2008 and it has never recovered. I had a full time assistant then, but I cannot afford that now.”

He offers still photography, video and production services for overseas photographers. “Recently,” he says, “I bought a drone for footage from the air.” But he prefers to get to know his subjects more closely an approach used for his two books on Japanese tattoos. Back in the Czech Republic, tattoos were associated with crime or gypsies “who did it with a fork” so when he saw the full body tattoos of Japan he was hooked. At the Sanja Matsuri he met the son of tattoo artist Asakusa Horikazu and later became close to the master.

Although tattoos are associated with criminal elements in Japan, too, things are changing. Hladik says: “It was never my interest to investigate who was a yakuza or not. I was under the wing of the master. I photographed for him and for my own interest.” In fact, in some ways he found the “undergound” tattoo scene similar to the “underground,” away from prying state powers, that he’d known in his youth and always very friendly.

Hladik spent two month long stints in Tohoku after the 3/11 disaster. The photos of two girls whose single mother had died in the tsunami, were among the powerful shots later exhibited at the FCCJ. He also used the exhibition to raise a collection for the girls.

Now, after 16 years here, a return to the Czech Republic is “on the horizon.” This is partly to bring his children up at least somewhat Czech, but he also has concerns about the life of teen agers in Japan sexualized girls and game immersed boys and hopes to escape that in Europe.

But until then he is looking for a project to spend time and depth on perhaps based around the changes in Tokyo as the city gears up for its second Olympics. Offering various services, however, can sometimes leave him torn. “It’s trying to find a balance,” he says. “If I did more production work you might have more money, but then my photography suffers!”

Andrew Pothecary is the art director of the Number 1 Shimbun.