Issue:

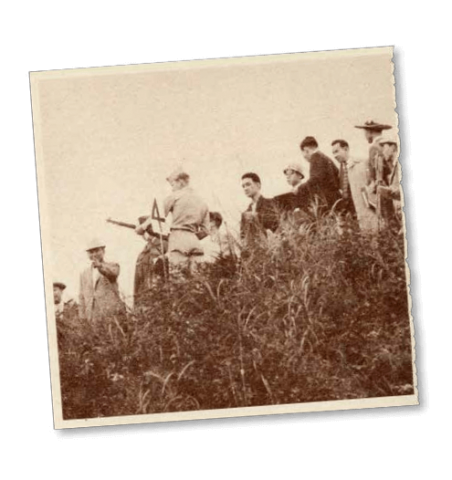

A Japanese magazine of the time shows William Girard at the firing range during the investigation.

Death by firing range

Some 60 years ago, the killing of a Japanese wife and mother threatened the U.S.-Japan agreement on the treatment of crimes by U.S. forces .

by MARK SCHREIBER

On June 30 this year, Kenneth Franklin Shinzato, a 32 year old civilian working at Kadena Air Base in Okinawa, was officially charged with the rape and murder of Rina Shimabukuro, age 20. It was the latest in a string of crimes committed by U.S. forces personnel in Japan that continues to cause some people to question the U.S. Japan military alliance, which has permitted American bases to remain after the end of the Allied Occupation in 1952. And while it has led to mass protests and even a mention at the recent Abe Obama summit meeting, it was another killing six decades ago that in terms of the sheer attention it received in the press, governments and courts of both countries strained the bilateral relationship like no other.

The “Girard Incident” took place on Jan. 30, 1957, when a unit of the 8th Calvary Regiment was training at a firing range at Camp Weir in Somagahara, a mountainous area in Gunma Prefecture. During a break around midday, Specialist 3rd Class William S. Girard, age 21, and another soldier were ordered to guard a machine gun and some field jackets near one of the hills of the maneuvering grounds.

Local people, mostly poor farmers displaced by the expansion of the camp, were allowed to enter the area when it was not being used for training, to tend to their fields, and collect brass shell casings and lead and other metals from bullets, mortars, grenades and other ordnance. They supplemented their incomes by selling the scrap to local brokers, who in turn sold it to recyclers in Maebashi, the prefectural capital.

“Before [the Girard Incident], many of us would creep into the impact area, dig holes in which to hide, and wait for the shells to drop. We would note the spots and rush out to pick them up during a lull in the firing, then dash for cover again before the next barrage began,” a local farmer and shell scavenger told future FCCJ president Ken Ishii, who was reporting for International News Service.

THAT MORNING, SEVERAL DOZEN shell pickers had swarmed the hills. So the commanding officer ordered that only blank rounds be used for the afternoon exercises. During the break, according to some witnesses, Girard flung some expended cartridges into the bushes “like feeding chickens” to watch the scavengers scramble to collect them, then fired in their direction to scare them off.

Girard’s M1 rifle had been fitted with a grenade launcher. He inserted an empty rifle cartridge into the launcher, a violation of rules, and without aiming, fired over the head of a Japanese man. When the scavengers began running, he launched another cartridge, which struck Naka Sakai, a 46 year old mother of six, in the back. The cartridge penetrated several centimeters into her back and tore her aorta, causing nearly instant death.

The shooting was not immediately reported by military or local authorities. It only became public after members of the Socialist party broke the story to Japan’s national newspapers, which published their first reports of the incident on the back pages of their Feb. 3 editions.

So SP3 Girard was headed for court. The only question was which one. In 1953, Japan and the United States had signed a so called Administrative Agreement that established criteria for determining whether Japanese or U.S. military courts had jurisdiction over personnel involved in civil and criminal matters on and off U.S. bases in Japan. Known today as the Status of Forces of Agreement (SOFA), it gives both parties the right to waive their jurisdiction in any incident in which they feel they have a right to try the accused.

Both parties claimed jurisdiction over the case. The U.S. Army insisted Girard had been on duty and hence should be tried in a U.S. military court. The Japanese side claimed that shooting Sakai did not constitute “performance of official duty” as stated in the agreement.

On May 16, the U.S. Army, after deliberations with Japanese authorities, and probably in consideration of Japanese public opinion as well as the legal particulars, waived its claim. The next day, however, the U.S. Secretary of Defense ordered the Army not to release Girard pending further investigation.

On May 18, the Maebashi district prosecutor indicted Girard, which meant that if the waiver stood, he would be tried in the Maebashi District Court.

GIRARD’S FAMILY IN THE U.S. went to court in an attempt to reverse the U.S. government’s decision to waive jurisdiction. They were supported by veterans, politicians and others who recalled Japan’s treatment of some Allied POWs, or otherwise harbored negative images of Japan, arguing that Girard would not receive a fair trial in Japan.

For the rest of May and June, a veritable who’s who of American and Japanese leadership from President Dwight Eisenhower, Secretary of Defense Charles E. Wilson, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, and Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, to Prime Ministers Tanzan Ishibashi and Nobusuke Kishi, LDP deputy Yasuhiro Nakasone, and House of Councilors member Jiichiro Matsumoto became involved. Emperor Hirohito, drawn into the controversy by a letter from the mayor of Girard’s hometown, replied through an aide that he “could not possibly intervene in the matter because of the Japanese Constitution.”

The family’s case made its way through the courts until, on July 11, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Girard’s constitutional rights would not be denied by a trial in a Japanese court and that the jurisdictional agreement between Japan and the U.S. was proper. The court also noted that Japan, as a sovereign state, had the right to try people who violated its laws.

The trial convened on Aug. 26. Girard was defended by Tokyo attorney Itsuro Hayashi, and legally advised by U.S. Army attorney Major Stanley Levin. The prosecutor demanded a five year sentence for shogai chishi (bodily injury resulting in death), which is tantamount to manslaughter. On Nov. 19, the Maebashi District Court’s three judge bench found Girard guilty and sentenced him to three years imprisonment, suspended for four years. The judgment, Hayashi later wrote in the monthly Bungei Shunju, fit the statistical “average” for manslaughter cases in Japan, and was probably less severe than a court martial sentence.

American defense attorney Melvin M. Belli who in 1963 had defended Jack Ruby against charges of murdering Lee Harvey

The U.S. government paid Sakai’s husband a condolence gift of $1,748.32. Upon accepting the money, he remarked, “I do not thank you for it.”

Oswald, the accused assassin of President John F. Kennedy attended at least one court session. Belli, though disappointed that Hayashi had dismissed his advice to showcase Girard’s wife in the courtroom, praised how the judge prevented spectators and the media from turning his courtroom into a circus in his 1960 book, Belli Looks at Life and Law in Japan.

In his book, Belli also described the scene at the predecessor of the FCCJ. “Hundreds of foreign correspondents sat, oiled up their typewriters, checked train schedules and, at the last minute, called for the impossible hotel reservations at the picturesque little village 80 hot miles north of Tokyo.”

Among them was Pulitzer Prize winner John Hersey, famed American author of Hiroshima, who covered the case for the Associated Press. “Before the killing,” Hersey wrote, “Girard was a kind of bumpkin clown. He drank quite a bit and ran up petty debts in the Japanese shops near his camp. He is taciturn to the point of woodenness; he failed for three days to tell his Japanese sweetheart that he had killed a woman, and she learned of the incident over the radio.”

THE BOBBED HAIR AND round face of Girard’s girlfriend, Haru “Candy” Sueyama, who he married on July 2, soon became a familiar figure in the media. She was six years older than the soldier, and the two had been living together from the previous November.

Some reports mentioned that Sueyama had been born in Taiwan and not set foot in Japan proper until age 16. Some English reports described her as a “camp follower,” and she received several threats but she eventually earned the media’s sympathy as a woman who stood by her man and made serious efforts at social observances and religious practices.

The weekly Asahi Gurafu pictured her kneeling in tears before Naka Sakai’s grave in a Shinto style family cemetery, Naka’s husband and youngest daughter standing beside her. “Who’s the big sister, and why is she crying?” the 4 year old girl asked her father. The caption related he was lost for words.

The U.S. government paid Naka Sakai’s husband and their six children a condolence gift of $1,748.32 (¥629,394) an amount described as “a fortune” for someone in Somagahara. Upon accepting the money, he remarked, “I do not thank you for it.”

Girard had tired of the attention. “Now that it’s over, me and Candy would both like some quiet,” he told a U.P. interviewer shortly before he was to leave Japan. “I’ll be glad when the flashbulbs stop popping and we can live like other people. I don’t think that I need any more publicity just now.”

On Dec. 6, Girard and Haru boarded a military transport ship for San Francisco. Prior to their departure, he was demoted to private, and after reporting for duty at an army base near his Illinois hometown, he was dishonorably discharged, dashing any hopes of remaining in the military.

In October the following year, weekly magazine Shukan Josei ran a story about the couple, who had settled in Girard’s hometown of Ottawa, Illinois. In August, “Candy” had given birth to a girl. “Bill,” meanwhile, had bounced between jobs. The article hinted that Haru, as a foreign bride who spoke little English, led a lonely existence. But another women’s magazine, the monthly Fujin Asahi, reported that she was happy.

The couple had another daughter and moved to southern California. Girard died in 1999 at age 64. Haru lived until 2013, passing away around age 85.

Since the end of the Occupation in 1952, sporadic crimes by American servicemen and their dependents have rekindled the long smoldering and emotional debate over the rationale for U.S. military bases in Japan. Okinawa, with by far the largest U.S. presence, appears to be the only prefecture that posts annual crime statistics by members of the U.S. military on its web site.

The LDP and other parties that favor keeping the U.S. bases maintain that the security, economic and other benefits afforded by their presence outweigh negative effects like the crimes, even felonies, committed by military personnel. Statistics show that crimes by members of U.S. armed forces have declined significantly over the years, and are currently below the local crime rates for Japanese civilians.

The families of Naka Sakai, Rina Shimabukuro and other victims, are unlikely to be impressed by such arguments. But their sentiments have not led to significant changes in the status quo.

Mark Schreiber currently writes the “Big in Japan” and “Bilingual” columns for the Japan Times. He would like to thank William Wetherall for his contributions to this article.