Issue:

October 2023 | Cover Story

Johnny & Associates has finally admitted decades of sexual abuse by its founder, Johnny Kitagawa. What are the lessons for the media in Japan, and will the agency survive? David McNeill talks to Daisuke Takahashi, a reporter for weekly magazine Shukan Bunshun, which led coverage of the story.

On September 7, Julie Fujishima announced she was stepping down as president of Johnny & Associates, the talent agency her uncle, Johnny Kitagawa, founded in the 1960s. The resignation followed a dam-burst of claims that Kitagawa had raped and abused children in his charge for more than half a century, under the noses of the company’s staff and the media.

Fujishima’s fate rested on the publication of a report by a panel led by Makoto Hayashi, a former prosecutor general. Kitagawa’s assaults on his stable of trainee stars stretched back at least until the 1960s, Hayashi concluded. Fujishima had to go, he insisted, because she and her mother Mary (Kitagawa’s sister) knew of the assaults but effectively ignored them.

This conclusion undermined a mealy-mouthed “apology” by Fujishima in May following an FCCJ press conference by Kauan Okamoto, a former Kitagawa protégé. Fujishima said she “couldn’t confirm” the abuse claims with Kitagawa (who died in 2019) and insisted she was "not aware" of them at the time. Victims who heard the apology said they simply didn’t believe her.

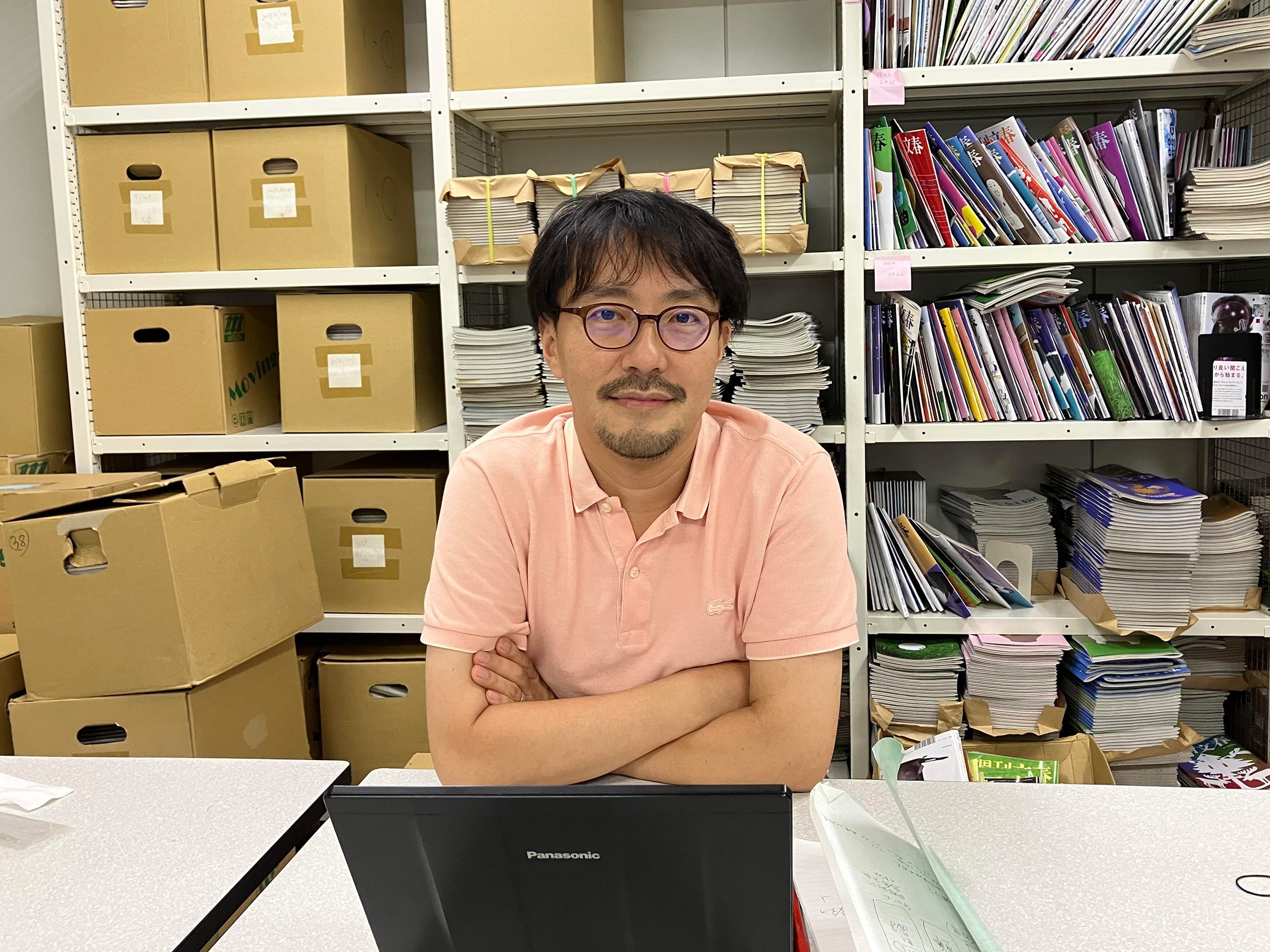

Fujishima’s departure appears to draw a line under a deeply toxic scandal that was decades in the making. But Daisuke Takahashi, a reporter for the weekly magazine Shukan Bunshun, is one of many who has his doubts. “I don’t think it will end her involvement with the company,” he says during an interview at the FCCJ. “She’ll likely continue to work behind the scenes.”

Takahashi points out that Hayashi’s panel was hired and paid for by the family-run agency and, while the severity of its conclusions was surprising to some, they provide a clean exit for the embattled president. “She always wanted to step down. She hates being in the limelight. If she was to say ‘I’m quitting’, she’d be accused of running away. This way looks more natural.”

Risk taker

Bunshun can lay claim to have risked more than most of its rivals in helping to fill the “submissive void” in reporting on the allegations against Kitagawa. It famously faced down the agency in court two decades ago, winning the legal right to – at the very least – cast suspicion on its notoriously reclusive and controlling founder. The magazine’s partial victory was mostly ignored by the rest of the media.

Since the case was disinterred by a BBC documentary in March, Takahashi and his team have interviewed 29 men who say they were abused by Kitagawa. The youngest was just eight years old. Among the victims was Okamoto, who gave an on-the-record news conference at the FCCJ in April that the Asahi Shimbun said had changed the atmosphere in Japan “for good”.

Okamoto returned to the FCCJ on September 8 to, in his words, put a lid on the stinking pot he had opened six months earlier (see story below). Remarkably, he wished Fujishima well. This was despite enduring furious trolling by the agency’s army of fans who said he was chasing fame, not justice. “There were times when I felt that I couldn’t take it,” he admitted. “But I want Johnny’s to survive.”

Not everyone is as forgiving. Many critics expressed disbelief that Johnny & Associates planned to retain its name, permanently memorializing one of Japan’s worst sex offenders in the title of its largest talent agency. And there was anger that Fujishima was due to stay on as representative director, switching to a behind-the-scenes role. She declined to say if she would divest any shares in the company.

Not long after Fujishima’s press conference, reports emerged that the agency was considering a name change after all. According to a post on its website, the possible name change was part of discussions on “the future of the company, taking into consideration opinions and criticisms”.

The apparent volte face came as a string of companies, including Nissan Motors and the Asahi Group, ended their commercial ties with the agency, saying they would no longer use celebrities signed to Johnny's & Associates for promotional work.

https://news.livedoor.com/article/detail/24969820/

There is widespread resentment over decades of media self-censorship regarding the allegations against Kitagawa. In July, Takahashi won a joint FCCJ award with the BBC for his magazine’s reporting. In his acceptance speech, he recalled that urging Okamoto to speak at the FCCJ was a strategic move. “We knew there was little chance that the Japanese press would report (the issue) so we calculated that if the overseas media covered it, the domestic media might follow.”

“The responsibility of the Japanese media throughout the abuse is extremely heavy”, he added. “When we asked the victims why they had not spoken up till now, many said they had revealed the abuse but they felt that their stories had been ignored, and that they felt crushed. As a result, the public didn’t hear the victims, and their number continued to increase.”

Freedom of the Press Awards Ceremony 2023, July 21, 2023 - YouTube

Takahashi agrees that Okamoto’s FCCJ presser was the fuse that relit the story in Japan. “The newspapers were the first to break ranks, then came television. Of course, they have the deepest connections to Johnny’s, so it was most difficult for them. But watching TV coverage of the abuse felt revolutionary, it felt like a new era. It had once seemed completely unthinkable.”

Down, but not out

Not every media outlet has come clean, however. Network broadcaster TBS explored the Kitagawa scandal on its Saturday evening special, Hodo Tokushu. Close up Gendai, NHK’s primetime evening news show, broadcast a short survey of the case. But other broadcasters still fear to tread. TV Asahi, for example, has steered largely clear, Takahashi noted, possibly because of its flagship Friday-evening show, Music Station (Myūjikku Sutēshon), which relies heavily on the agency’s roster of airbrushed boy bands.

It is also too soon to write off the agency, cautions Takahashi. No fewer than 57 TV programs in Japan (as of April 2023) still use artists from the Kitagawa stable as hosts, actors or regular guests. Some serious TV programs, such as NTV’s News Zero, use guest presenters from the agency. “Many TV producers still believe that if they don’t use Johnny’s stars they won’t grab an audience,” he says. Indeed, as ratings sink, TV producers might be more inclined to play safe.

Johnny’s is down but not out. Yet, the myth of its invincibility has been finally broken, as a Newsweek Japan cover story argued in May. As evidence, Takahashi cites the case of Hideaki Takezawa, a former star and executive vice president of Johnny & Associates who quit last year to set up his own production company. At least one TV company has agreed to hire actors from Takezawa’s agency – a move that once would have risked a blackballing by Johnny’s.

Many commentators noted that Suguru Shirahase, the agency's infamous enforcer, appears to have gone to ground. As vice president, he ringfenced the Kitagawa family, protecting them from journalistic enquiry for decades, and cajoling and strongarming the media into accepting the agency’s terms. Like Mary and Johnny, Shirahase distrusted and hated the internet and carefully policed it for unauthorized use of copy (one reason why it was almost impossible for years to find images of Kitagawa himself).

In one of Kitagawa’s few legacy interviews, for NHK, Japan’s most powerful broadcaster was persuaded by Shirahase to film him only from the neck down. According to ex-journalist Michinari Yanagida, one of Shirahase’s tactics was to smother potential scandals involving the agency’s stars by discouraging serious newspapers from covering them and favoringthe tabloids and TV, which could be relied on to lob softball questions.

That world is gone. The change of management at the company could leave more space for staff members who understand how K-pop and the internet has revolutionized the industry, says Takahashi.

The world has changed

Another result of the Kitagawa revelations is that the understanding of sexual grooming and abuse in Japan has changed for good, Takahashi says.

“In the 1990s, the term ‘sexual harassment’ was being used for the first time. The fact that the head of Japan’s largest entertainment company was involved in such behavior was considered a ‘scandal’ rather than as criminal behavior or dangerous. Magazines didn’t cover the story out of a sense of social justice. It was a human-interest story.

“When we looked at this in 1999, indecent assault (強制わいせつ罪) was considered a matter between men and women – there wasn’t much consciousness of male-on-male sexual abuse. If you went to the police, they’d likely say the victim should have resisted. The media, even newspapers, didn’t recognize this as criminal behavior. But society now understands that this was a crime”.

The Kitagawa story has given Bunshun a much-needed lift in its profile. It is a relative publishing minnow in Japan, with a weekly print-run of 500,000 copies (of which about 300,000 typically sell), and a staff of just 30 to 40 journalists. By contrast, The Asahi Shimbun, Japan’s liberal flagship newspaper, has over 2,000 journalists and its morning edition has a circulation of more than four million.

Covering the Kitagawa scandal did little to increase hard-copy sales, according to Takahashi (circulation of the mass weeklies is down to a quarter of its peak in 1995). But publishing its biggest stories online for a fee of ¥300 a time every Wednesday – the day before the print edition goes on sale – has proved a smart move. In early September, the magazine’s scoop about Fujishima’s imminent retirement attracted around 10 million page views.

Bunshun’s model of aggressive and successful reporting could hasten Japanese journalism’s shift to publishing more online content. As former editor, Shintani Manabu, noted in 2020: “If you report accurately and well, and people support and trust you, they’ll buy your stories.”

Kauan Okamoto – survivor and whistleblower

If any one person can claim to have brought Johnny & Associates crashing down to earth, it is Kauan Okamoto. His FCCJ press conference in April, where he accused Kitagawa of repeatedly abusing him between 2012 and 2016, prompted several dozen other survivors to speak out.

That was followed a highly critical report by the the U.N. Working Group on Business and Human Rights, which focused worldwide attention on the agency and pressured it into commissioning the Hayashi probe. Yet, on his return to the FCCJ in September, Okamoto insisted he had no intention of destroying the agency, adding that he had been surprised by the fallout.

“That wasn’t my aim at all,” he said. “The fact that they have come as far as acknowledging what happened, and announced the change in the presidency, and compensation for the victims, I think this is a step forward.”

Okamoto said he harbored no feelings of revenge toward Kitagawa and felt “gratitude” for the world that he had introduced him to. While he said he “respected and supported” the agency’s new president, Noriyuki Higashiyama, he was puzzled that he had decided to not change the firm's name. “Honestly, I’m very surprised by that. I thought it was nearly 100% certain they’d change the name. I think this will have a negative impact on the company.”

For his role as chief whistleblower, Okamoto was trolled and heavily criticized. He cried when he recalled the impact the controversy had had on his mother, who was caught up in the crossfire. He accepted, he added, that no matter what else he did in life, he would forever be associated with the revelation that he was sexually abused in his teens. “There were times when I felt that I couldn’t take it,” he said. “But I have no regrets about speaking out.”

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for the Independent, the Economist and the Chronicle of Higher Education.