Issue:

October 2023

Few knew, but a July 1945 attack on Osaka neighborhood was a practice run for a new and terrifying kind of bomb

This past summer, as in previous years, memorial observances were held for atomic bomb victims in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Shortly before those two events, on July 26, another ceremony was held in Osaka. It was attended by about 120 people who gathered at Onrakuji, a Buddhist temple in the city’s Higashi Sumiyoshi ward, to observe the 78th anniversary of the dropping of a mogi genbaku (mock-up atomic bomb). On that date, the Jabbit III, a specially configured "silverplate" B-29 flying from Tinian, Mariana Islands, dropped the 4.5-ton bomb on the Tanabe neighborhood, damaging over 400 homes and other buildings, killing seven and injuring 73 people.

https://www.onrakuji.com/模擬原爆資料館/

On hand to convey her memories was 98-year-old Shigeko Tatsuno, a school instructor, who on that day in the summer of 1945 had accompanied her students to work on the second floor of a factory producing buttons for military uniforms. The factory had run out of materials to work with, so her group had moved to another room. About 10 minutes later, at 9:26 a.m., a very large rock and debris from a nearby ryokan inn came crashing through the roof.

"If we hadn't moved to that other room, I wouldn't be here to tell you what I witnessed," Tatsuno said.

The July 26 ceremony, which was streamed online, was also attended by representatives from nine primary and middle schools, who recited pleas for peace.

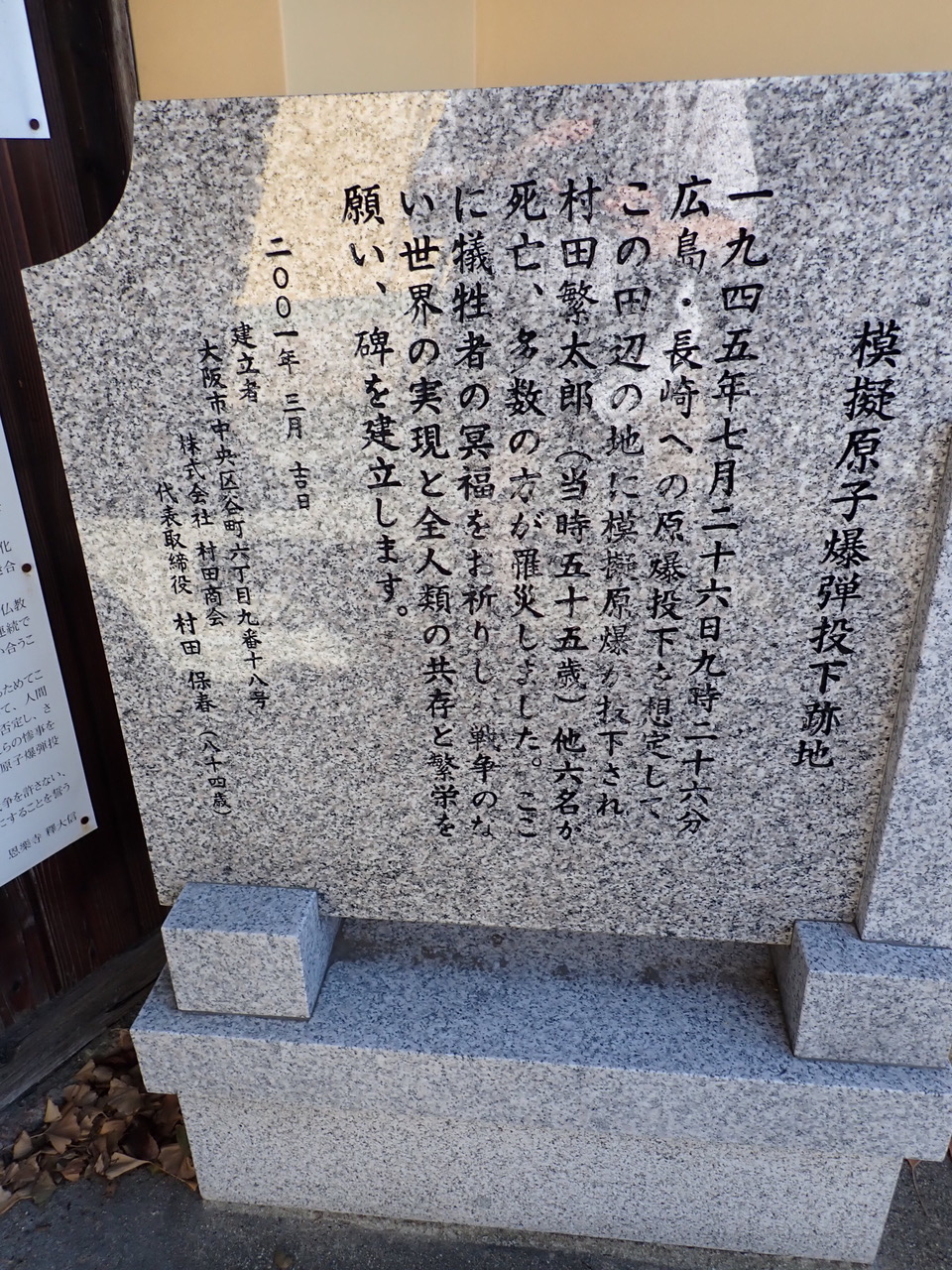

The monument at Onrakuji reads:

On July 26, 1945, at 9:26 a.m., a mock-up atomic bomb, which preceded the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, was dropped on the Tanabe neighborhood. Shigetaro Murata (then aged 55) and six other people were killed, and numerous others injured. This monument was erected with prayers for the victims to rest in peace, for the realization of a world without war, and out of the desire for the coexistence and prosperity for all humankind.

Erected on this day in March, 2001

The mock-up atomic bomb that struck Tanabe was one of 49 dropped on cities and towns in Japan, including its capital Tokyo, between July 20 and August 14, 1945. It has been estimated that 400 people were killed and 1,600 injured in these raids.

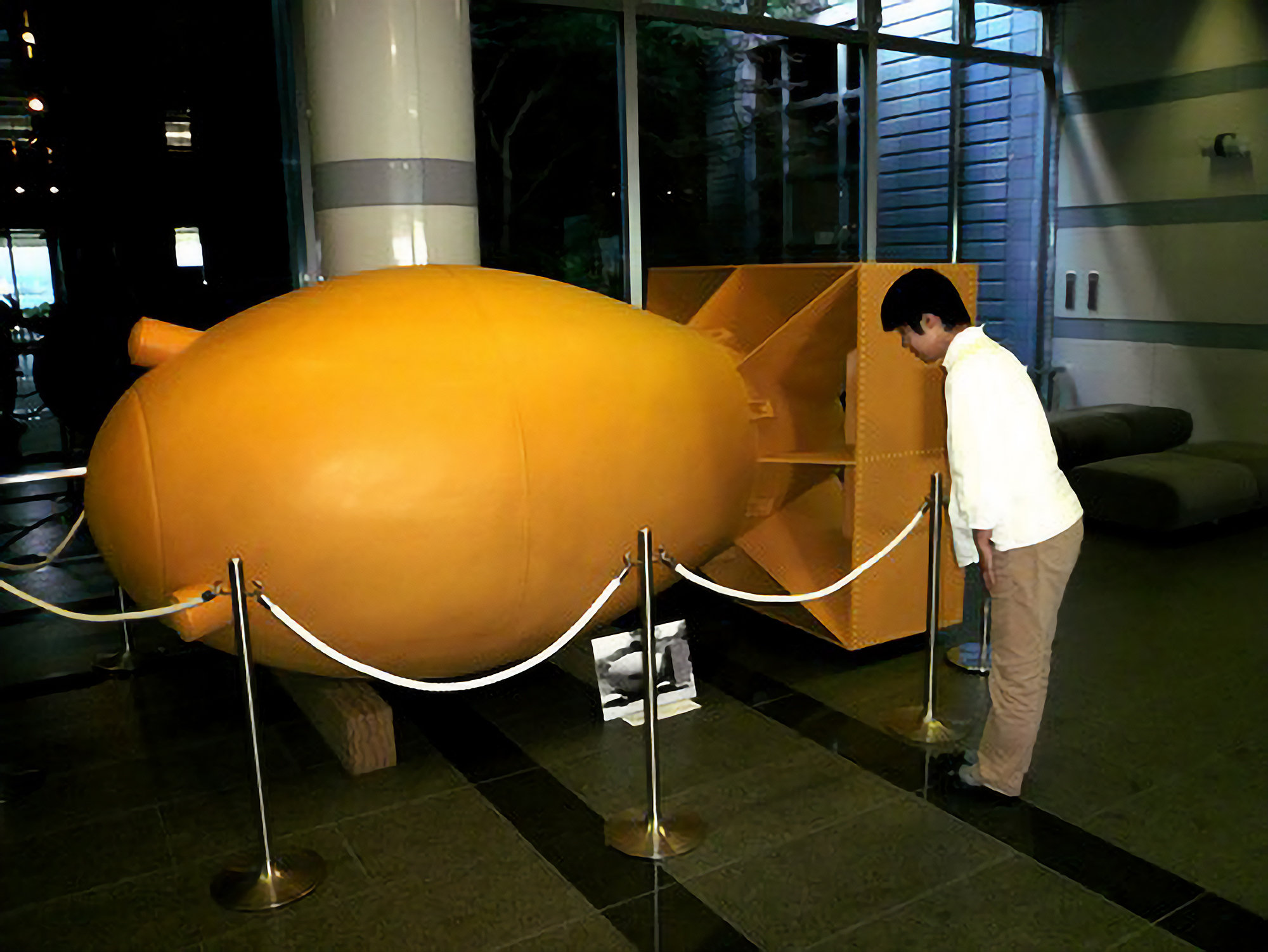

The Americans first referred to the bombs as "blockbusters" and later "Pumpkin bombs" – so nicknamed because of their ellipsoidal shape and yellow color. They closely resembled “Fat Man,” the plutonium bomb dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, except that they were packed with 6,300 pounds of Torpex high explosive. Crews of the Tinian-based 509th Composite Group used the Pumpkins to rehearse how they would drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Of the 49 missions, 36 dropped their bombs based on visual sighting of their targets, and 13 used radar. No planes were lost due to anti-aircraft fire or malfunction, although one suffered slight damage when it was attacked by a Japanese fighter.

Among the 13 B-29s of the 509th Composite Group that flew these preparatory missions from North Field on Tinian were the Enola Gay, which flew two missions on July 24 and July 26, and the Bockscar, which flew three missions on July 24, 26 and 29. These were the two planes that would drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August.

It is not entirely clear when, and to what extent, Japanese military and civilian organizations first learned that the 49 Pumpkins dropped on their cities had been practice runs for the atomic bombings.

Much of the materials regarding the Pumpkin raids now in hand can be attributed to efforts by Tsutomu Kaneko, a teacher at a middle school in Kasugai, Aichi Prefecture. In 1986, Kaneko organized a group to compile events in Kasugai during the war years, and in the course of his research he interviewed former workers at local munitions factories. Kaneko also traveled to Washington, where he pored over declassified wartime data at the U.S. National Archives. On 103 spools of microfilm he found and transcribed records of the missions flown by the 509th, and a map of Japan showing the targeted cities for the Pumpkin air raids.

“I was lucky,” Kaneko was quoted as saying. “People voiced amazement that an amateur like myself managed to come up with the material.”

As reported in Shukan Kinyobi (Aug. 4-11), from 1992 Kaneko began corresponding with municipalities on the list, and as of August 2023, data is said to be lacking on only three of the 49 Pumpkins dropped.

In addition to Tanabe, other communities bombed by Pumpkins also maintain exhibits, have conducted memorials or published materials, including Otsu City (Shiga Pref.), Zuiryuji temple (Fukushima), Hoya City (now part of Nishi Tokyo City), Nagaoka City (Niigata), and Nagoya (Aichi). In 2019, Hiroko Reijo published Pumpkin: Mogi Genbaku no Natsu (Pumpkin: The summer of mock-up atomic bombs) (Kodansha), a 128-page reader for schoolchildren said to be the first book in Japanese dedicated to the topic.

"It's possible that many things have yet to be uncovered," Kaneko remarked. "That's why we want to keep our network functioning."

How necessary were the Pumpkins to the U.S. war effort? Apart from development of the atomic bombs themselves, Manhattan Project scientists confronted a myriad other challenges, such as obtaining aircraft capable of flying long distances and dropping a very large and different bomb on its target. The B-29 Superfortress made its debut fairly late in the war, first appearing in the Pacific theater on 15 June, 1944, when 47 B-29s took off from bases around Chengdu, China to bomb steel plants in Yawata, now part of Kitakyushu City. That marked the first bombing raid against the Japanese home islands since the Doolittle Raid of April 1942.

As the Manhattan Project progressed, concerns arose that crews flying the first atomic bomb missions might find themselves on suicide missions.

As related in Ruin from the Air: The Enola Gay's Atomic Mission to Hiroshima (1977), the following exchange took place at Los Alamos on September 19, 1944, between the Manhattan Project's scientific director, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and Lt. Col. Paul Tibbets, commander of the 509th Composite Group.

“Colonel,” said Oppenheimer, “your biggest problem may be after the bomb has left your aircraft. The shock waves from the detonation could crush your plane. I am afraid that I can give you no guarantee that you will survive.”

Tibbets told Oppenheimer that his pilots usually flew straight ahead after releasing their payload. By flying above 30,000 feet, he assured the physicist, the B-29s should be safe.

To this, Oppenheimer replied, “You can’t fly straight ahead because you’d be right over the top when it blows up and nobody would ever know you were there." The solution, he explained, was to turn tangent to the expanding shock wave.

"Turn 159 degrees in either direction as fast as you can and you’d be able to put yourself at the greatest distance from where the bomb exploded."

Prior to the unit's transfer to the Pacific in May 1945, crews of the 509th practiced their high-altitude drops and extreme maneuvers at Wendover Army Airfield in Utah using non-explosive bombs filled with concrete, designed with drop characteristics identical to real atomic bombs. Over Japan, however, they switched to "live" bombs.

With the exception of Tibbets, no members of the 509th were informed of the Manhattan Project, and security remained so tight they would not learn of it until "Little Boy" was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6. Thus, a cover story had to be concocted regarding their practice missions over Japan.

According to Tinian and the Bomb: Project Alberta and Operation Centerboard by Don Farrell (2018), at a meeting at Los Alamos in Feb. 1945, Gen. Leslie Groves repeated a suggestion from Gen. Lauris Norstad, senior Army Air Forces officer involved in the Manhattan Project, that to maintain secrecy, crews were to be told the purpose of their mission in only a general way:

In discussing the blockbuster, the organization should be told that it ... would continue to be necessary to make a lot of very peculiar tests. In discussing the nature of the high explosive ... the members could be told that it was a new explosive and was an improved variety of RDX (Research Department Explosive), also that the new explosive or explosives would be undergoing numerous changes and improvements.

In War's End: An Eyewitness Account of America's Last Atomic Mission (1997), Bockscar pilot Major Charles W. Sweeny wrote of his Pumpkin missions:

On July 20 we were finally cleared to fly missions over Japan. The targets were Otso [sic], Taira, Fukashima [sic], Nagaoka, Toyama, and Tokyo. With the exception of Tibbets and a handful of the men he’d brought in at Wendover, most of the members ... would be flying their first combat missions.

These missions over Japan would have the same profile as the real one, if it ever happened. Each airplane would carry a single Pumpkin filled with [the high performance explosive] Torpex, drop it on a target, and then take vertical photographs of the damage. Although inflicting damage on the enemy would be welcomed, it was a collateral objective. We were dress-rehearsing for the big day. The crews would be navigating long-range over water to a primary city in heavily defended enemy territory and dropping the weapons visually from 30,000 feet on a specific enemy target.

"Tibbets was prohibited from flying any of these combat missions," Sweeney added. "His capture by the Japanese could jeopardize the entire Manhattan Project. Within the 509th, he was the only one who knew practically everything."

The origin of the list of targets for the Pumpkin missions is not entirely clear, although it's possible it was provided by Gen. Curtis LeMay, commander of 21st Bomber Command based on Guam. Broken down by prefecture, 8 Pumpkins were dropped on Aichi, followed by Fukushima (6); Ehime, Hyogo and Toyama (4); Yamaguchi, Niigata and Shizuoka (3); and 1 or 2 on Kyoto, Gifu, Fukui, Mie, Wakayama and Tokyo. The most deadly of the 49 raids, dropped July 29 by the Straight Flush on the naval arsenal in Maizuru City, Kyoto, killed 97 people.

Straight Flush also made the most controversial of the Pumpkin missions on July 20. Unable to make a visual sighting over Tokyo, pilot Capt. Claude Eatherly, in defiance of specific orders, used radar to target the imperial palace. The bomb missed by several hundred meters, landing by the outer moat at Gofukubashi, just northeast of Tokyo central station. One person was reported killed and 62 injured.

Archival data concerning the death and destruction wrought by wartime bombings, broken down by prefecture, are maintained by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications and can be viewed online.

Given the limited scale and seemingly random selection of targets over a broad area of the country, along with less than one month of use, it is unlikely that anyone suspected the Pumpkin raids were practice runs for a new and different type of bomb.

In a research paper published in 2010, Yoshiteru Kikuchi compiled data on how the Pumpkin raids were reported in the local and national newspapers. His findings (in Japanese) can be found online at the Toyo University Repository for Academic Resources.

https://toyo.repo.nii.ac.jp/record/9616/files/asiabunka431-10.pdf

"Most of the newspapers referred to the Pumpkin as having been a 'one-ton bomb,'" Kikuchi wrote. "The heaviest bomb in Japan at the time was about 80 kilograms (the main gun shell of the battleship Yamato weighed 1.46 tons), which may have led many reporters to believe that it was more powerful than 80 kilograms... [but] it was difficult for reporters to imagine that the American bombs weighed as much as 4.5 tons.

"Moreover, the B-29s had a bomb capacity of 4 to 9 tons... Japan's ground-launched aircraft were limited to a carrying capacity of 1 ton (the Type 2 flying boat was about 1.6 tons). These figures provide a true reflection of the differences in Japan's and America's industrial capabilities."

With the war ended and preparations being made for the bombers to withdraw from Tinian, it was decided that 66 Pumpkins remaining on the island (44 still in crates and 22 under canvas covers) were no longer needed. They were disposed of with much of the secrecy characteristic of the project they had supported. As Farrell writes, around the time surrender ceremonies were held on the USS Missouri in early September:

...crews hoisted the Pumpkins onto flat-bed trucks, transported them to the LCT dock and loaded them onto barges. The LCT took them ten miles out to sea ... a crane operator lifted the Pumpkins and dropped them into the sea ... no one actually saw the bombs.

A translator, columnist, author and mystery fiction enthusiast, Mark Schreiber has lived in the Far East since 1965.