Issue:

Obituary | December 2022

Hideaki Kase used his connections to the FCCJ and the foreign community to promote his nationalist beliefs about history

After the 1997 death of Princess Diana - the nearest Britain has to a modern secular saint - journalist Christopher Hitchens sneeringly eulogized her “jet-setting, disco-minded, super-rich sybaritism” and smelled “floral fascism” at the tsunami of national grief she inspired. In 2011 Hitchens told the heavily Christian audience of Fox TV that evangelist Jerry Falwell was a charlatan and said if he was given an enema “he could be buried in a matchbox”. Mother Theresa, concluded Hitchens, was “a fanatic, a fundamentalist and a fraud”.

When criticized, Hitchens pointed out that the cultural taboo on speaking ill of the dead should apply only to private individuals. Public figures who had traded in political views and used the media for their own ends for much of their lives were fair game. Journalist and author Hideaki “Tony” Kase was no Mother Theresa and was hardly as famous as any of Hitchens’ targets but he was a public figure, one who used his considerable resources to inject himself energetically into the toxic debate about Japan’s wartime misdeeds.

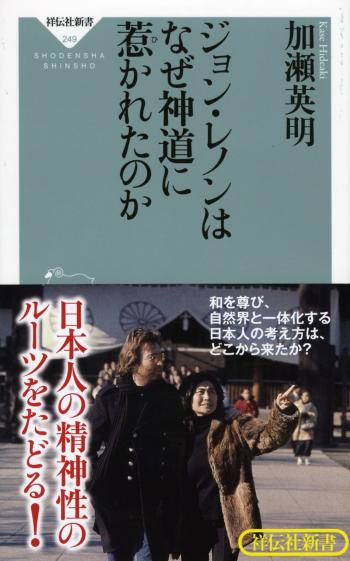

Influenced by his diplomat father, Kase worked to promote his beliefs about history by engaging with foreign journalists, including members of the FCCJ (his lobby group distributed literature right into the mailboxes of club members), foreign writers, commentators, and audiences through an English website and a string of publications, even leveraging his connections to John Lennon (via his cousin Yoko Ono). He once wrote a book about how Lennon was attracted to Shintoism.

Kase’s consistent contribution was to argue that Imperial Japan was not a tormentor of its Asian neighbors but a liberator of them. “We liberated India,” he asserted in one interview. “The campaign in Imphal [March-July 1944, when Japan invaded India to attack Allied forces] sparked Indian independence. Every Japanese person is certain” (here Kase raised his voice) “that the war was important! It was the war that brought equality between the races.” Kase said the war was the reason why Black commentators could be seen on television.

Kase’s professed respect for the well-being of his fellow Asians did not always translate well. Chinese culture was “all about lies”, he said, which by extension meant that Chinese accusations of war crimes could be dismissed. The upshot of such views could be read in the bestselling 2013 book Eikokujin Kisha Ga Mita Rengokoku Sensho Shikan No Kyomou by FCCJ stalwart Henry Scott Stokes, for which Kase wrote the foreword (the book sold over 100,000 copies).

“The Tokyo Trials were a total sham, serving only as a theater for unlawful retribution,” intoned the book (later published as Fallacies in the Allied Nations' Historical Perception as Observed by a British Journalist). “And as for the ‘Nanking Massacre,’ there has not been one shred of evidence attesting to it. However, the Chinese are hell-bent on using foreign journalists and corporations to spread their propaganda throughout the world. There is no point in even debating the comfort women issue.”

The English-language book provoked speculation about whether it represented the views of Scott Stokes (who confessed he didn’t understand it) or Kase, but it was entirely consistent with the latter’s views. In the documentary Shusenjo (2018), Kase said lying is also “part of Korean culture”. Asked to cite a reputable historian, he said he “doesn’t read books by other people” and at one point seemed to attribute the rise of America’s civil rights movement to Japan. Discussing the fury that "comfort women" denialism provokes in South Korea, Kase called Koreans “cute,” like children.

Kase added that raping comfort women was “impossible” because “you have to pay them”, and said if he ever met them, he would say that he feels sorry for them, and then ask how much money they had earned. In an interview with Reuters, Kase explained that he and his colleagues were dedicated to "our conservative cause. We are monarchists. We are for revising the constitution. We are for the glory of the nation”.

Kase absorbed his loyalty to establishment Japan and his historical outlook at home, and in particular from his father, Toshikazu Kase (1903-2004). As a career diplomat, Kase’s father was personally involved in the fateful agreements his country signed with both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union on the eve of the war, and in 1945 he took part as one of Japan’s representatives at the surrender ceremony aboard the battleship USS Missouri. Ten years later, the Kase Snr. was appointed Japan’s first ambassador to the United Nations, and after retiring, continued to act as a personal adviser to prime ministers.

In 1981, Kase founded and led the National People’s Council to Defend Japan, a far-right organization that, among other projects, published textbooks of its own making about Japanese history. Kase Jnr. continued that work. The Society for the Dissemination of Historical Fact, which he chaired, says he published 89 books, including the co-authored English-language Kamikaze: Japan’s Suicide Gods. He was also a director of the Alliance for Truth about Comfort Women and a supporter of denialist causes, including the (unsuccessful) three-year legal battle to dismantle a statue in Glendale, Southern California and the (unsuccessful) attempt to have Shusenjo cancelled.

Hideaki Kase, the Ultranationalist Figure Who Wanted to Make Japan Great Again

Haaretz.com

Kase was reliably hawkish on defense issues. “Article 9 must be deleted,” he stated. “Every sovereign nation has the right to maintain such forces.” He said that instead of doubling the defense budget, as the government debated, “we need to triple it”. He hoped Japan would develop a nuclear bomb and said it needed to become an arms exporter. “It’s too bad Putin didn’t attack Ukraine when (Shinzo) Abe was in power. Abe would have taken advantage of the development to double the budget.”

Kase also expressed regret that abortion was not perceived as a crime because it would help Japan’s declining population. He was “not completely against immigration” but against allowing in Chinese, Vietnamese and Indonesians. “I am for letting in people with needed professions. One-hundred thousand, even 200,000 a year, is reasonable. People from Myanmar who know how to behave should come. Koreans are very welcome – my wife is Korean.”

In the last few years of his life, Kase made strenuous efforts to recruit Jewish journalists to write about the campaign to build a statue to Lieutenant General Kiichiro Higuchi (covered in this issue). “He almost certainly felt such coverage would give validation to the story,” said one of these journalists. Most treated him with suspicion. His supporters may take comfort in the fact that the Japan he departed is inching closer to the vision he tirelessly propagated.

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for The Independent, The Economist and The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Tim Hornyak is a Canadian writer based in Tokyo. He has worked in journalism for more than 20 years, and written extensively about technology, science, culture and business in Japan, as well as Japanese inventors, roboticists and Nobel Prize-winning scientists.