Issue:

Flags of our fathers: Looking for a battle

The Yashima, built for the Imperial Japanese Navy in the 1890s, in a print belonging to the author.

Will the squabbles over the possibility of seeing the Rising Sun flag at next year’s Olympic games turn into a real battle or fade in the onslaught of the next controversy?

By Mark Schreiber

My late friend, Adrian Johnston, born in 1934 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, served in the Korean War and developed a great affinity toward Japan. Years later, he would still visit at every opportunity, taking time off from his jewelry manufacturing business to enroll in Japanese language summer school courses.

In the late eighties, on one of his trips here, he phoned me, sounding puzzled.

“Do you think Japanese are becoming more right wing these days?” he asked.

“I can’t really say I’ve noticed,” I replied. “Why are you asking?” “I’ve been watching this marathon on TV just now,” he told me, “and the spectators on the roadside were all waving Rising Sun flags while cheering the Japanese runners.”

It took a moment before it dawned on me. It was obvious my friend had confused the corporate flag of the Asahi Shimbun sponsor of the marathon for the Rising Sun flag. The Rising Sun flag, with rays emanating from a red circle, was and is still used by the Japanese military, as opposed to Japan’s official national flag, a red circle in the middle of a white background. The Asahi’s version has rays emanating from a quarter of a red circle in the lower corner.

It seems the similarity had revived traumatic childhood memories of the Rising Sun flags he saw as a boy in UP news reels and John Wayne movies like Back to Bataan and The Sands of Iwo Jima. I patiently explained the Asahi’s involvement and added that its corporate logo notwithstanding, the newspaper’s political positions were, if anything, the diametric opposite of right wing.

But since the above exchange nearly 30 years ago, I can’t recall one conversation I’ve had with anyone on the topic of Japan’s Rising Sun flag. It’s an image I rarely see, and as far as I know, it cannot be found on a public flagpole anywhere in the Tokyo metropolis, certainly not at the National Diet building or the Ministry of Defense in Ichigaya.

YET IT HAS BECOME the hot spot of the latest controversy between this country and its closest neighbor.

It began with two fairly lowkey events in late August. The first came when officials from the Korean Sport & Olympic Committee on a visit to Tokyo lodged a complaint with their hosts. They wanted a proactive ban put in place to keep displays of the Rising Sun flag out of Olympic venues. Then, the same week, another Korean group representing handicapped athletes protested the design of the medals for the Tokyo Paralympics, which it claimed “evoke the image of the Rising Sun flag.”

These South Korean groups and other critics of the flag see its continued use by the Japan Self Defense Forces as evidence that unlike Germany, where symbols of the former Nazi regime are prohibited by law, Japan has not engaged in serious efforts “to eradicate militarism” since the war. Now the flag issue is being lumped with such other festering historical points of contention as “comfort women” and forced labor during the war.

On Sep. 5, Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga remarked at a press briefing that Japan saw no need to take action to halt displays of the flag.

A week later, Seoul’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism announced it had written to IOC President Thomas Bach expressing “disappointment and concern” that the Japanese organizers have not taken steps to ban displays of the flag.

On Sep. 23, the head of the Chinese Civil Association for Claiming Compensation from Japan chimed in with a letter to the IOC that made similar demands. The same day, North Korea’s official government newspaper, Minju Choson, predictably jumped into the fray, criticizing Japan for “Plotting to transform the ‘war criminal Rising Sun flag’ into a ‘symbol of peace.’” On Sep. 30 the Yonhap news agency reported that legislators in South Korea’s national assembly passed a resolution urging a ban, by a vote of 196 to 3.

Following Suga’s remarks, other government officials and organizations fell into line. In a press conference on Sep. 6, Education Minister Masahiko Shibayama stated, “We are aware that claims have been raised that it carries a political message, but it is regularly flown, for example, during joint military exercises with other countries. Banning it from being brought into [Olympic] venues is not being considered, and I am in agreement with chief cabinet secretary Suga on this.”

JAPAN’S MINISTRY OF FOREIGN Affairs, meanwhile, posted a PDF file on its web site under the title “The Rising Sun Flag As Part Of Japanese Culture.” It explained, “… the design of the Rising Sun Flag is seen in numerous scenes in daily life in Japan, such as in fishermen’s banners hoisted to signify large catch of fish, flags to celebrate childbirth, and in flags for seasonal festivities.” It added, “For more than half a century, these flags have been playing an indispensable role to show the presence of the Self Defense Forces vessels and units, and are widely accepted in the international community.”

On Sep. 24, Masanori Takaya, spokesman for the Japan Olympic organizing committee, defended the flag to reporters, “The design of the Rising Sun flag is widely used in Japan and does not convey any political message. We are not planning to ban it from being brought into the venues.” Takaya nonetheless did not entirely rule out proactive measures, stating, “From the perspective of preventing trouble, our guidelines are to consider measures that might be necessary for dealing with the issue.”

Some local media took the side of the flag’s detractors. “In general, where else can one see the Rising Sun flag other than at hate demonstrations?” wrote author Koichi Yasuda in Shukan Kinyobi on Oct. 11. “Last month, at a rightist demon stration demanding Japan sever diplomatic ties with South Korea, you could see as many Rising Sun flags in the crowd as the Hinomaru. And what was their intention? Harassment and intimidation.”

WHILE THE PRESENT CONTROVERSY represents the first time Koreans have demanded the Rising Sun flag be banned inside Japan, protests outside the country began several years ago, with mixed successes. In 2013, a female Korean student in France successfully led a campaign forcing the retail chain Fnac to remove a promotional poster bearing an illustration showing the rising sun motif together with a comic character brandishing a Japanese sword.

At a soccer game played in Suwon, South Korea in April 2017, supporters of the Kawasaki Frontale club nearly provoked a post game riot by waving the flag. After the game, Korea took its complaint to the Asian Football Confederation (AFC), which ruled that use of the flag constituted a “discriminatory offense.” The Kawasaki team was fined $15,000 and obliged to play a home game to no audience.

Yoshiaki Sei, author of the book Soccer and Patriotism, believes that permitting Rising Sun flags to be waved at Olympic events isn’t worth the potential downside. “If Japan were to garner negative reactions from the international community or formal complaints from foreign governments, it’s possible that Japanese teams will get penalized,” he cautioned in Weekly Playboy. “I think the organizing committee’s decision [not to ban the flag] is an extremely risky one.”

HOME-GROWN PRIDE

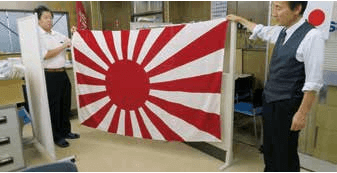

Tatsuo Kobayashi, 63, is president of Tokyo Seiki, Inc. He is the fourth generation in his family’s flag making business, which was founded in 1937.

Kobayashi’s Japanese flags are entirely home grown, and as proof he offers photos from his factory in Gunma, where the flags, produced using the silk screen method, are run off on an automated assembly line.

Rising Sun flags constitute only a miniscule amount of TOSPA’s total business, and there’s no evidence of any surge in demand. Overall sales of Japanese flags and those of other nations (of which TOSPA produces 206) will no doubt benefit from next year’s Olympics.

Rising Sun flags are sold via the company website, and as far as Kobayashi can tell, their buyers appear to be individuals rather than organizations. TOSPA offers the army flag (where the red dot is positioned at mid center) in five sizes, and the naval flag (with the off center dot) in 32 varieties, including sets with flagpoles. They are constructed of durable, wrinkle free polyester.

An impressively large naval flag is the largest item in the catalog, measuring 140 x 210 cm and priced at ¥19,500, which is probably suitable for flying on the mast of a destroyer or coast guard patrol boat.Kobayashi declined to comment on the current political squabble which caught him unawares. “For some 50 years, nobody’s raised any issues about those flags. And then all of a sudden this happens,” he said, shaking his head in bewilderment. (M.S.)

Essayist Keiko Kojima, writing in the Sept. 14 edition of the weekly magazine AERA, was adamant in her opposition to the flag. “What kind of person would wave the Rising Sun flag in the Olympic Stadium?” she asked. “At which game, under which situation, and for what intended purpose would they wave it? During the summer, a time when we mourn the many who died beneath that flag at home and abroad, it’s a sight I don’t want to see.”

South Korea’s raising the issue of Rising Sun flags seems to have caught Japan unprepared. The Japanese government has made clear it’s taking a hands off position, trusting the nation’s sports fans who have shown exemplary behavior during the Rugby World Cup to do the right thing. It will be interesting to see how this story develops. But if one thing’s certain, no one wants next year’s games marred by acts of violence, whether by exuberant fans or rowdy nationalists.

Mark Schreiber currently writes the “Big in Japan” and “Bilingual” columns for the Japan Times.