Issue:

February 2022

The Yomiuri Shimbun’s agreement with Osaka Prefecture raises troubling questions about the critical role of the media

On December 27 last year, the Osaka prefectural press club held an eyebrow-raising media conference with Osaka Governor Hirofumi Yoshimura. Sitting at the same table as the governor was Gaku Shibata, president of The Yomiuri Shimbun, who was there to make an unusual, and troubling, announcement: Japan’s largest daily newspaper was signing a “comprehensive cooperation agreement” with the Osaka prefectural government.

Under the agreement, Yomiuri staff and Osaka bureaucrats will work side-by-side in eight different areas: education and human resource development, information dissemination, industrial revitalization, community development, public safety and security, child welfare, health, the environment, and “other areas in-line with the purpose of the agreement”. Yomiuri employees will be expected to directly advise Osaka bureaucrats on how to craft their message to the public more effectively.

The troubling question, in case it wasn’t already obvious, was spelled out by critical commentators such as former Japan Times columnist Philip Brasor, who wondered if the Yomiuri was, in effect, agreeing to become media advisor and promoter for future Osaka-based events and projects, such as the city’s controversial attempts to land a casino resort. Didn’t this deal make the Yomiuri Osaka’s PR organ, he asked.

Some Japanese media, including The Yomiuri Shimbun and The Nishinippon Shimbun, have cooperation agreements with cities and towns in other parts of the country; the Yomiuri signed one in November 2020 with Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture, where a major U.S. Marine Corps base is located. https://www.city.iwakuni.lg.jp/soshiki/10/32704.html

But the Yomiuri’s agreement with Osaka prefecture is unprecedented in scale and has drawn heavy criticism from nearly 200 journalists, lawyers, scholars, and senior business executives in Osaka and elsewhere.

“The unification of government authority on one side of the news coverage and a news organization on the other is nothing but an act that distorts the public’s right to know and endangers democracy,” said a letter of protest that had attracted over 52,000 signatures on change.org as of late January.

Even former Prime Minister Yukio Hatoyama expressed concern on Twitter, warning the agreement could turn the newspaper into nothing more than a propaganda organ, not only for the prefecture but also for Yoshimura’s local party, the right-of-center Osaka Ishin, which is the base for the national Japan Restoration Association party that Yoshimura co-heads. https://twitter.com/hatoyamayukio/status/1474303820926951425

Yoshimura and Shibata spent much of their nearly half-hour press conference defending the agreement and insisting it would not lead to editorial restrictions or preferential access for the Yomiuri. Local reporters, however, were particularly concerned by the newspaper’s agreement to cooperate with the prefecture in hosting the 2025 Osaka Expo, which is already facing cost overruns, post-Olympics public apathy and limited overseas agreement on exhibits.

Online commentators warned that Yomiuri readers might end up searching in vain in the months ahead for unfavourable stories about Expo 2025.

Yoshimura and Shibata brushed aside those concerns, saying the Yomiuri was capable of making its own judgements about Expo 2025. But few in the Osaka-based media sound convinced. Their concerns are not merely for the larger issues of freedom of the press and democracy but also for their own reporting.

What would happen, for example, if a reporter with the Osaka prefectural press club had to put tough questions to official sources while working on a critical story about the Expo, Osaka’s casino bid or Yoshimura and his party? Would word of the probe reach the prefecture’s official media partner which is, after all, tasked with helping the prefecture get positive messages out?

Likewise, Yomiuri reporters in Osaka are said to be wondering what the agreement means for their relations and reputation with news sources that may be critical of either Yoshimura or Osaka prefecture. That includes their relations with local chapters of other major political parties that disagree with Yoshimura and his party on major issues.

So why the agreement, and why now?

Commentators have suggested one reason is the desire by the Yomiuri to secure a relationship it hopes will lead to major government-sponsored advertising revenue between now and the Expo. Others wonder if one purpose of the agreement is to get Osaka prefectural public schools to subscribe to prefectural newspapers, newsletters, or online “educational” content that has passed through the hands of Yomiuri editors and echoes their views of the present – and the past – in the hope the children of today will become subscribers as adults.

Or is the newspaper’s goal bigger than just increasing sales? Does it want to play political broker between Yoshimura’s Japan Renovation Party, which dominates Osaka politically and could be poised for gains in the Upper House election this summer, and the ruling Liberal Democratic Party?

The two parties, or at least the Japan Renovation Party and the Shinzo Abe-Yoshihide Suga wing of the LDP, are ideological soulmates, in lockstep on practically every major economic, social, and political issue. Yoshimura wants the party to grow beyond its Osaka base, which it has so far struggled to do. What better way to gain national exposure than to tie up with the nation’s largest newspaper, including in areas of the country far from Osaka?

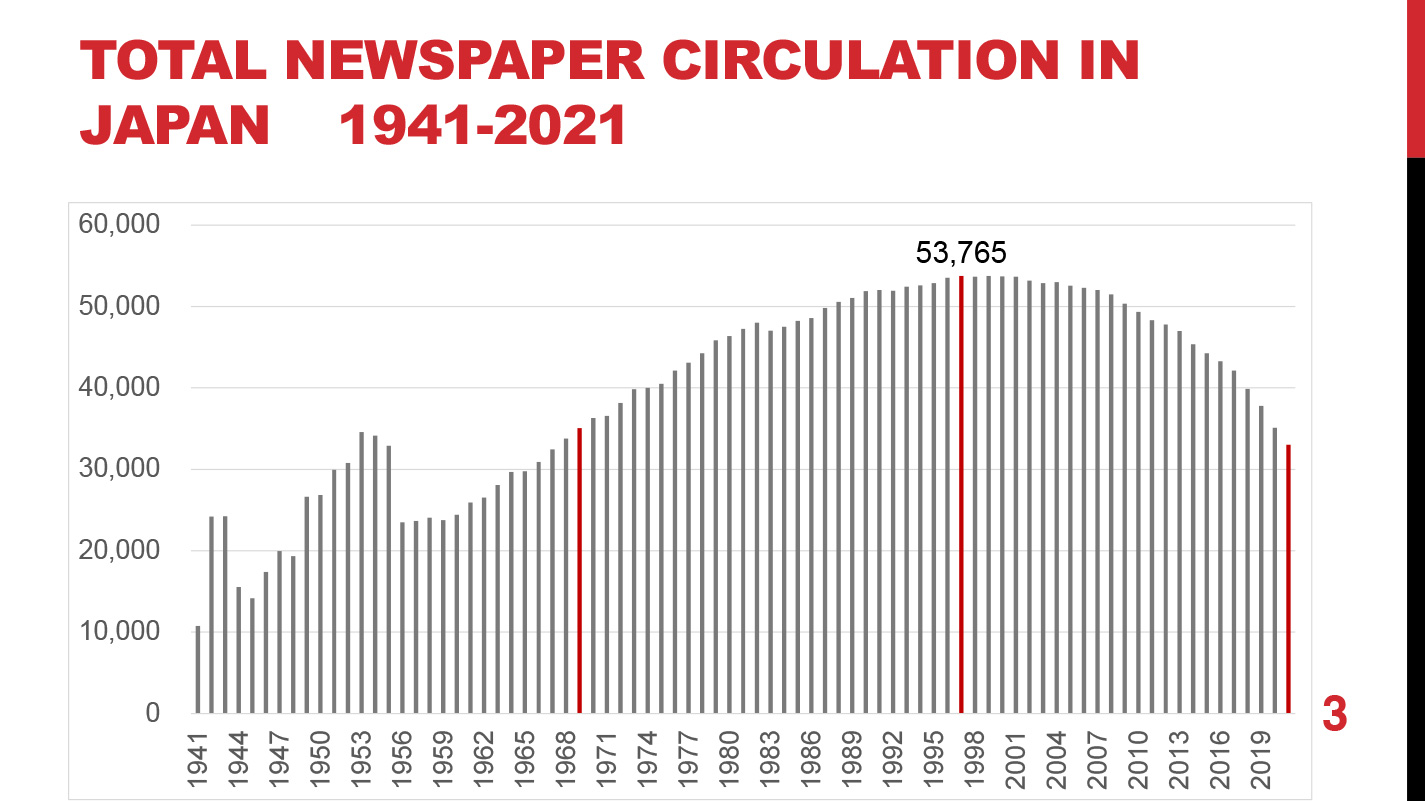

After all, as of the end of 2020, the Yomiuri Media Data survey (https://adv.yomiuri.co.jp/mediadata/files/2030_circulation.pdf) showed the paper had the largest share of the household market in nine prefectures, including Tokyo, and the second largest share, usually after local papers, in 26 others. Like all newspapers, the Yomiuri is nervously eying the relentless decline in daily circulation, which has fallen by over 16 million since peaking at nearly 54 million in 1997.

Shibata, however, insisted nothing sinister was afoot, and that the agreement was intended to provide the local community with useful information, including accurate, critical guidance in time of emergencies. The Yomiuri, he said, was not going to turn into a pushover for prefectural officials, explaining that the company’s code of conduct forbids reporters from accepting instructions from third parties or bending the facts to promote a particular person or group.

“If we think something is desirable, we’ll say it’s desirable, and if we thing something is wrong, we’ll write that it’s wrong,” he said at the press conference. Whether readers, in Osaka or elsewhere, will believe him and continue to support the paper remains an open question. The answer is likely to impact whether the Yomiuri-Osaka deal is an anomaly or a disturbing portent for journalism and freedom of speech in Japan.

H.L. Stone is a veteran journalist and occasional university lecturer who is familiar with the Osaka press club system and the Osaka-based print and broadcast media.

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s events committee. He was previously a correspondent for The Independent, The Economist and The Chronicle of Higher Education.