Issue:

“In some distant day, when this Indochina War can perhaps be put in some sort of perspective, students of Journalism may be able to chronicle the work of the thousands of Men and Women who covered the conflict”

– Edward Q. White,

Vol. 4 No. 11, Nov. 1972

Club votes to move

With a target date at the end of the year, the Club will relocate atop the new Yurakucho Denki Building. The move was overwhelmingly approved by the general membership on Monday, Oct. 13.

Not that it was overwhelmingly welcomed. The move was accepted as inevitable. Those members who had taken advantage of an opportunity to inspect the proferred premises were impressed by the view from on high. . . .

Dissenters found the present Club comfortable and convenient, and concerned that reliance on elevators would discourage patronage. Supporters felt the new plant would be a magnet for increased patronage, especially at night.

– Irwin Chapman, Vol. 7 No. 10, Oct. 1975

A new boom in making weapons

Some of the statements of Mr. Yasuhiro Nakasone, Defense Agency Director, have stirred the weapons industries to such an extent that it is now referred to as the danyaku buumu. Nakasone is a long-time advocate of Japan’s rearmament. . . . He is of the opinion that Japan’s diplomacy in the international arena will not be effective unless it is backed up with military power.

– Sivapali Wickremasinghe,

Vol. 3. No. 4, Apr. 1970

Bomb at our door

It was just after I had come downstairs to the Club office that it happened. [The bombing of the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries’ head office by the East Asia Anti Japan Armed Front.] The loud shock of the blast left little doubt in my mind that something very serious had occurred, either a bomb or a gas explosion. Everyone around me seemed stunned and not a little frightened. I was told later that several correspondents upstairs listening to Foreign Minister Toshio Kimura immediately jumped up and ran out.

I dashed out the side door and ran toward the street. . . . I ventured out from behind the edge of the building, crossed the street and started down the sidewalk toward the smoke. Several jagged pieces of glass hurtled down, smashing into the sidewalk only a few feet behind me. Instinctively, I ran into the middle of the street and continued to the next block. Just ahead of me was Happy Mayger with his camera and one of Ian Mutsu’s MGM cameramen, Kakun Sho, grinding away with his movie camera. . . .

Then I saw it. The lifeless body of a naked man lying in the gutter, one leg completely blown off. It was a shocking sight to see a human being smahed and torn like that. It was impossible to make out a face. I turned away and noticed a man lying in the street, obviously badly injured, with someone trying to lift up his head. Another covered him with a coat. . . .

An American businessman named Garfield Becksted said he’d been crossing the street coming up from the Club when the bomb went off. “I saw a Japanese woman lying on the sidewalk across the street. I rushed over and tried to take her in my arms, but she died before I could do anything,” he said.

– Andy Adams, Vol. 6 No. 9, Sept. 1974

The Okinawa story after the reversion

They say if you drive north of Koza and Kadena Air Base, Okinawa is really quite nice – green mountains, white sand and blue seas. But in the 20-mile-long strip south to the concrete-block capital of Naha, you have to endure the incredible congestion of the grittiest, sultriest urban military sprawl this side of Norfolk, Virginia. It’s the worst of Japan and America combined. . . .

The setting is hardly scenic. Some 600,000 of the 900,000 Okinawans are jammed into the strip, cheek by jowl with the U.S. Army’s logistics depot, most of the 80,000 Americans, cheap California dependents’ housing, used car lots, root beer stands and enough saunas and steam baths to accommodate the U.S. Marines.

Maybe the Japanese can do something with the place. The Americans certainly haven’t. The town planners missed the boat, or weren’t invited, when the boom got underway in the 1950s. Everyone admits that the bases monopolize the best land, but no one knows what to do. . . .

Maybe it will all be transformed in the post-reversion, non-nuclear world.

– John M. Lee, Vol. 4 No. 3, May 1972

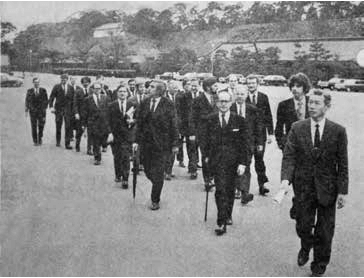

Emperor meets press

Emperor Hirohito of Japan, seated in the splendor of an audience room in the Imperial Palace a few weeks ago, defended his role before and during World War II as that of a constitutional monarch. . . .

The meeting with foreign newsmen, which officials of the Imperial Household Agency emphasized was an audience and not a press conference, was limited to the media of nations the Emperor and Empress visited on the trip that was the first for a reigning emperor ever outside of Japan.

But the event in itself, like the journey through Alaska to Europe, was another indication of an increasingly self confident Japan that is groping to find better communications with the rest of the world.

Until now, the Emperor’s contacts with the foreign press have been limited to private audiences with senior news executives and an occasional audience in which correspondents were merely introduced to him. He also saw two American correspondents briefly just after WWII. Japanese newsmen see the Emperor briefly once or twice a year.

But today, in the spacious audience room known as the Shakkyonoma, with the ornate picture of a redmaned noh actor hung in the background, was the first time the Emperor permitted questions to be directed at him from foreign correspondents.

Under the rules set up by the Imperial Household Agency, the questions were submitted to the Emperor beforehand. But newsmen were allowed to ask one follow up question to each prepared question.

It was in response to those that the gentle and dignified Emperor was spontaneous and forceful. In one such answer he added to the historical record of the prewar and wartime period.

He recalled what is known here as the “Niniroku jiken,” an incident of Feb. 26, 1936, in which fanatic young army officers seized downtown Tokyo, held it for three days, and assassinated four government leaders.

Many historians have credited the Emperor for having ordered vacillating generals to put down the coup, but have lacked firsthand evidence. The Emperor said today: “At that time, some of the leaders of the government were missing, so I had to act decisively on my own.”

Similarly, near the end of WWII in 1945, the Japanese government was split between those who wanted to surrender and those who wanted to fight to oblivion. . . . He said today: “At the time of the end of the war, Prime Minster Suzuki left everything to my discretion, so I had to make a decision. But that decision was taken at the responsibility of Prime Minister Suzuki.” The Emperor indicated that he considered both actions within his prerogatives as a constitutional monarch.

– Richard Halloran, Vol. 3 No 12, Dec. 1971

Confessions of a female chauvinist

I hate men:When the spokesman at a press briefing says, “My, we have many lovely ladies among us today.”

When the maitre d’ rushes up to me and says, “I’m sorry but this table is for the working press.”

When another reporter asks me, “Where are you going today, to a fashion show?”

When they say, “When are you going to get married?|”

When they ask, “Isn’t it too hot to wear slacks?”

When I am taking pictures of a demonstration and male demonstrators smile at me.

A wire service’s Tokyo bureau, with its cross cultural representation of chauvinists, is to women’s liberation what the aborigines of Australia are to anthropologists – one of the last vestiges of primitive society where sexual equality is concerned.

– Kathy Talbot,

Vol. 7 No. 9,

Sept.1975