Issue:

October 2024

The speedy, prestigious Asia Express was Japan’s precursor to the shinkansen

I can't recall when I first became aware of the Asia Express, which before the Pacific War stood out as the fastest train in the Japanese empire. It ran not in Japan, but in the puppet state of Manchukuo. Many of my older Japanese friends had lived in Shanghai, Manchuria and Korea before and during World War II, so I had probably learned about it from them.

My interest was rekindled when I began researching the historical background of the shinkansen. Internet searches began turning up articles and blog entries about the Asia Express, which began service to Shinkyo (now Changchun) from Dairen (Dalian) on the morning of November 1, 1934.

A feature article in the Sankei Shimbun reported that two "Pashina-type" locomotives that had pulled the train were on display at a museum in Shenyang (formerly Mukden), in China's Liaoning Province. According to the article, however, access to the museum was restricted – as if its exhibits were politically sensitive – and during my first visit to Shenyang in June 2018, I struck out.

Fortunately, I found Shenyang to be a hospitable city with many historic sites, ranging from the Qing emperors' summer palace to the Mukden prisoner-of-war camp and a lively ethnic Korean enclave. A year later I returned for a second visit, and this time found the holy grail.

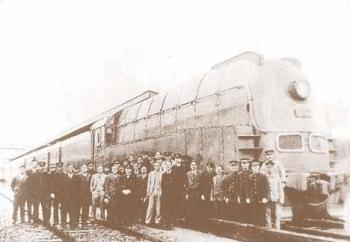

On September 19, 2019, my hired car pulled up outside a huge 80,000 square-meter building called the Shenyang Railway Museum. Once inside, I immediately spotted the object of my quest. As I approached, I reflexively reached out and laid my palm against an imposing blue locomotive bearing the Japanese katakana name tag Ajia 757 and felt a shiver of excitement.

Ninety years ago, the locomotive had pulled the Asia, a short-lived jewel in the crown of an area in northeast China measuring 984,195 square km (380,000 sq mi), more than 2.5 times the 377,975 square km of Japan proper.

Among the spoils of Japan's victory in the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05 was a railway renamed the South Manchuria Railway Company, called Mantetsu for short. The Russians had previously been granted concessions from China to build the original line, which was configured to a wide gauge of 1,524 mm, same as the Trans-Siberian Railway and other lines in Imperial Russia. During the Russo-Japanese war the Japanese military, obliged to utilize Japan-built rolling stock, had converted it to the 1,067 mm narrow gauge used in Japan.

Mantetsu's new management soon decided it would be practical to integrate its trains with the Chinese railway network, and the decision was made to modify the rail width once again, to the 1,435 mm standard gauge used in China. The changeover was accomplished in about 18 months.

Over the years that followed, Mantetsu rapidly developed into a huge conglomerate – referred to as Japan's "East India Company in China" – that combined railway, steamship and hotel operations with agriculture and mining, among others.

Despite the world being in the throes of the Great Depression, Mantetsu’s management decided to upgrade its passenger service, and in 1933 dispatched engineer Yoshizumi Ichihara to the U.S. to study passenger rail technology at four companies: Pullman Car and Manufacturing, Westinghouse, General Electric, and Carrier Engineering.

Upon his arrival in San Francisco, Ichihara confidently told the local Japanese-language newspaper, the Hokubei Asahi: “I have come to America for the purpose of producing the world's best railway in Manchuria. I am researching two aspects: the reduction in travel time between Dairen and Shinkyo (Changchun) to seven hours, and heating and air conditioning equipment.”

In addition to being the world's first fully air-conditioned train, improvements were poured into the design of Asia's locomotives. Designated Pashina – a portmanteau of Pacific and nana (seven) – a total of 20 locomotives were built at plants in China and Japan. Along with weight reduction through the use of lighter materials, its aerodynamic design was said to reduce wind resistance by as much as 30%. The locomotives also incorporated Schmidt type E superheaters and state-of-the-art automatic stokers that rapidly supplied coal to fuel the boilers.

Mantetsu's main line, which from 1932 had shared control with the state-owned Manchukuo National Railway, ran 701km from Dairen to Manchukuo's capital of Shinkyo (Changchun), with a travel time of 8 hours 30 minutes. From September 1935, the Asia's service was extended from Shinkyo to Harbin, and travel time over the entire 943.3 km route became 13 hours, with speed averaging 72.5 kph.

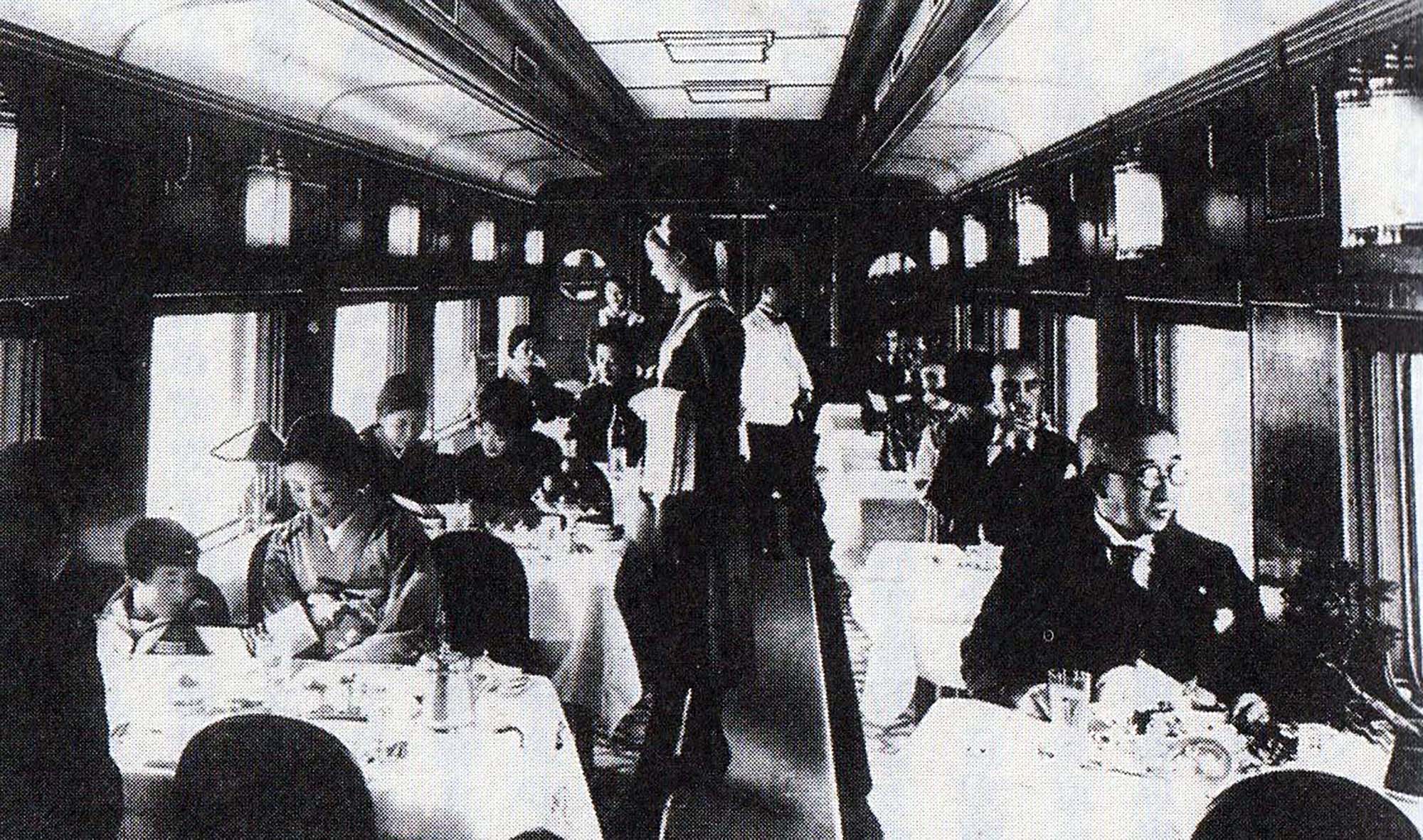

Compared with the Tokaido Shinkansen's maximum configuration of 16 cars with capacity of 1,340 passengers, Asia Express trains operated on a much smaller scale. Each northbound and southbound daily run typically carried up to 104 passengers in 1st-class sections, 68 in 2nd class and 88 in 3rd class. All carriages featured air conditioning, automatic doors, comfortable passenger compartments and a dining car featuring Russian waitresses “to satisfy the traveler's spirit”.

While not the world's fastest – from the mid-1930s steam locomotives in the U.K., Germany and the U.S. were regularly reestablishing new speed records – Mantetsu could make the claim to being operator of Asia's fastest train, with a top speed of 135 kph (84 mph). By contrast, the fastest train in Japan at the time, the Tsubame, achieved a maximum speed of 95 kph.

Due to wartime demands, the Asia's regular services came to an end in 1943, but Pashina locomotives remained in service in China until 1981. (Some Mantetsu rolling stock was said to have remained in use in North Korea into the 21st century.)

The success of the Asia Express is believed to have influenced an ambitious plan in 1938 to build a standard-gauge, high-speed steam locomotive that would support Japan's military expansion on the Asian continent. Plans had it running from Tokyo to Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, in nine hours. Its construction began in March 1941, but had to be aborted in June 1944 due to wartime budgetary constraints, and all that was left of the project were the Shin-Tanna tunnel near Atami and its memorable name, dangan ressha (bullet train).

Yet one more thing would come to tie Mantetsu to the Tokaido Shinkansen: a former Mantetsu director named Shinji Sogo (1884-1981), who is rightfully acknowledged as the "father" of the shinkansen.

Born in Ehime Prefecture, Sogo had begun his career with the Ministry of Railways, where he had been a protege of Shimpei Goto (1857-1929), one of the most influential figures in the late Meiji period. In 1906, Goto assumed the reins of Mantetsu as its first president, and would later head Japan's Railway Bureau.

In July 1930, at the urging of House of Peers politician Mitsugu Sengoku, Sogo was appointed a director of Mantetsu. Over the decade to follow, he would serve in various capacities until returning to Japan.

Biographical and historical data are lacking on any direct involvement by Sogo in the planning, creation or operations of the Asia Express, although it's likely he had at least traveled aboard it.

Rather, along with Mantetsu's day-to-day management issues, Sogo was regularly obliged to lock horns with the Kwantung Army, which shared control of Manchuria (and from 1932, Manchukuo) with the Mantetsu. It was large and unruly military force that often operated independently of the Tokyo government, and dealing with its hotheaded militarists was a thankless, stressful task. Despite reputed close ties to the headstrong general Kanji Ishiwara (1889-1949), a nemesis of prime minister Hideki Tojo, Sogo kept his head off the chopping block until returning to Japan.

The 71-year-old Sogo had been serving as chairman of the Railway Welfare Association when, against his better judgement, he was appointed head of the Japan National Railways in 1955. At the time, the JNR was beset by financial difficulties and labor problems. As Japan's economy recovered from wartime devastation, the cities along the Tokaido (Eastern Sea Road) were home to 40% of Japan's population and 60% of its manufacturing capacity. And while accounting for only about 3% of the entire JNR rail network, the Tokaido main line was forced to handle nearly one-half of Japan's total passenger and freight transport. It was literally creaking at the seams.

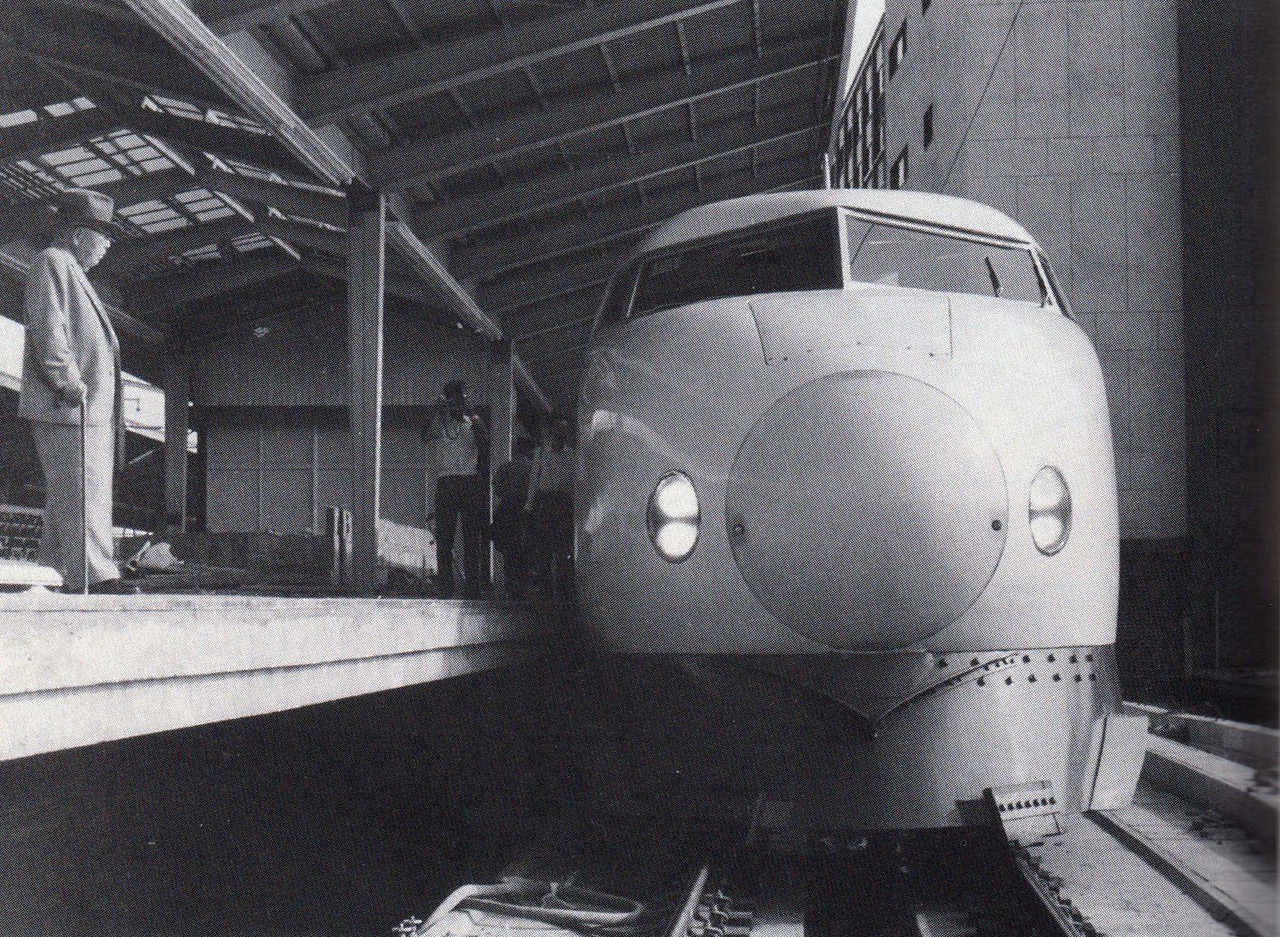

Sogo understood that with the construction of the Tomei and Meishin Expressways underway and expansion of domestic airline services, the JNR would soon be facing heavy competition. A new service would be needed, preferably one that would be fast enough to enable a comfortable, same-day round-trip between Tokyo and Osaka.

Sogo knew enough about rail technology to understand why Japan's narrow-gauge standard could not provide the stability needed for high-speed operation. Many local governments, however, opposed a standard-gauge shinkansen because such a line would essentially disengage their communities from the rest of the rail network. And travelers to destinations not served by shinkansen would have to disembark and transfer to other lines.

There was also the matter of funding. To make up for the projected shortfall, Sogo traveled to Washington to request a loan from the World Bank. Its directors politely listened to his plan for an electrified high-speed rail line but were skeptical. It was already the middle of the 20th century: was not rail travel fast becoming a thing of the past?

Struggling with his awkward English, Sogo demonstrated yet another of his many attributes – that of a persuasive salesman.

"If Japan is still an underdeveloped country," he argued, "Isn't that all the more reason why it needs a better railway? When you build a new house, it's natural to furnish it with new facilities. And when you build a new railway, it makes sense to use the newest technology available."

The bank was convinced but pared the amount of its loan from the requested $200 million to $80 million at 5.75% interest, to be repaid over 20 years. While that figure comprised only about 15% of the total of the shinkansen's construction costs, Japan felt put on the spot to repay a foreign loan so as to avoid any loss of face.

The gradual appreciation of the Japanese yen from ¥360 to ¥220 against the U.S. dollar worked in Japan’s favor, greatly reducing the burden in terms of both principal and interest. The loan was repaid in full in May 1981. Sogo lived to see his dreams come true, dying five months later at the age of 97.

Mark Schreiber is author of Shocking Crimes of Postwar Japan (Yenbooks, 1996) and The Dark Side: Infamous Japanese Crimes and Criminals (Kodansha International, 2001).