Issue:

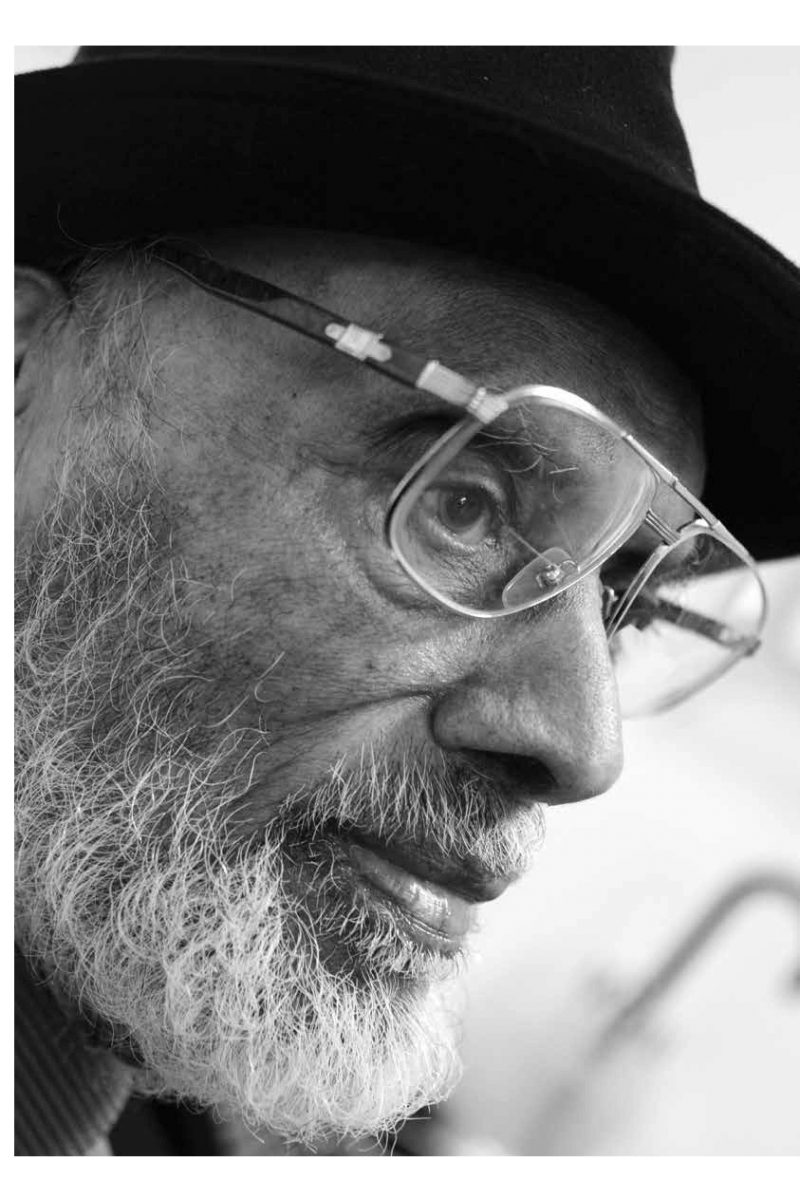

Vellayappa Chokalingham was born on Nov. 30, 1914 to a South Indian merchant family whose business empire stretched to Malay and Singapore. Many of the male family members of the well off clan had been sent to Europe for higher studies and, upon completing his education, the same opportunity was open to young Vellayappa. The young man chose to head in the opposite direction, however, and sailed to Japan with the dream of becoming an engineer specializing in power generation. It was an area that he hoped would be helpful in expanding the family business.

His first encounter with Japan came at the port city of Nagasaki on a sunny spring morning in 1935, and there was not the slightest hint that his stay in the country was going to be a very long one, or that it would cover turbulent times and be full of exciting endeavors. That first encounter did expose, however, the first few of many contradictions in Japanese life that he was to find curious.

As he sailed eastward from Singapore, he was pretty sure that he was going to arrive at a country that was preserving the oriental traditions that were much appreciated in other parts of Asia. Instead, the people he met at the port were all dressed in Western attire. Surely, he thought, the way they had taken to the Western dress code meant he could expect a deep knowledge of the languages of the West as well. That would be to his benefit, since he knew no Japanese and needed to get directions to the railway station from where he had to take a train to Tokyo. Instead, to his misfortune, no one spoke a single word of English and he had to find his own way to the station with much difficulty.

In Tokyo he rented a place near Shinjuku and enrolled at Kogyo University. It was a time when exiled Indians in Japan were organizing under the leadership of Rashbehari Bose with the idea of launching a liberation movement to free India from British colonial domination. As the Japanese army started moving westward, the movement received the patronage of the Japanese government, and it was some time during this period that Bose asked young Lingham to become his private secretary. Initially he was a bit hesitant as he thought accepting the offer might disrupt his study. Later, however, he decided to join Bose; his close association with the leader continued until Bose’s death in early 1945.

He travelled all over the Southeast Asian region with the movement leader, encouraging Indian expatriates to join the newly formed liberation army. However, many of their countrymen in Southeast Asia were suspicious of Rashbehari Bose’s motives. They saw him as a puppet of the imperial Japanese army, and were reluctant to step forward. This prompted the Japanese leadership to look for an alternative, and with the arrival of the charismatic Indian leader Subhash Chandra Bose in Tokyo in 1943 the leadership crisis was solved. By the time Rasbehari Bose returned to Tokyo to hand over the leadership to Subhash Chandra Bose, he was already seriously ill.

He travelled Southeast Asia with the liberation movement leader, encouraging Indian expatriates to join the newly formed liberation army.

Chokalingham, too, was ordered to return to Tokyo, where he was given a new assignment as a Tamil language radio broadcaster at NHK. The remuneration that he received for his service was quite hefty at the time, allowing him to lead a relatively well off life. He even had enough to sip coffee at the luxurious Imperial Hotel, where he once saw the legendary spy master Richard Sorge spending time with his cohorts. But that good time came to an end. Chokalingham remembers when Tokyo was the target of frequent U.S. bombing raids, and he had to run for shelter on a number of occasions when he was trapped in the street.

Japan’s unconditional surrender in August, 1945, led to a period of uncertainty. “It was a time of anxiety and fear,” he says, “because I belonged to the losing side and was waiting for my turn to be called for interrogation.”

But he needed work. The only opening he could see for someone with his skills was for interpreters. He was worried that for someone like him applying for that kind of job might turn out to be suicidal. Eventually, he made friends with a few Americans who encouraged him to get involved in interpretation. The call from the interrogators came while he was already working for the occupation.

His worries were for nought. “My interrogators came to a firm conclusion,” he says, “that I had done nothing wrong.”

His American friends also suggested that he try his hand at commerce, so in the 1950s he began operating his own import company. (The friends also began simplifying his name from Chokalingham to “Chuck Lingham” a name that has stuck.) Success followed quickly, and with his Japanese wife, Chuck settled down to make a good life in his adopted country. Later he established a new company that concentrated on importing metals for Gillette Japan, which he ran until his retirement almost 30 years ago. Chuck joined the FCCJ in 1967 and was given life membership in March 2005. He is now its oldest member. It has become his second home to the extent that, most days, he can be seen spending a few hours being waited on with great care by the staff and his friends at the Club.

From an obscure student activist dreaming of liberating his country to a very successful businessman and entrepreneur to a beloved fixture at our tables, Chuck has led his fascinating and active life to the full.

He celebrated his 100th birthday last month

Monzurul Huq represents the largest-circulation Bangladeshi national daily, Prothom Alo. He was FCCJ president from 2009 to 2010.