Issue:

January 2023 | Japan Media Watch

Japan’s use of imperial eras to indicate years has been an unlikely source of political controversy

A funny thing happened on the way to Emperor Akihito's abdication in 2019. As pointed out in a December 5 article in The Mainichi Shimbun, due to the monarch’s decision to step down – announced in 2017 – officials tasked with coming up with the name of the next imperial era had plenty of time to ponder the possibilities. Their earlier counterparts did not have that luxury when the Showa Era (1926-1989) changed to the Heisei Era (1989-2019), because Hirohito, posthumously known as Emperor Showa, died while still on the throne, as had almost all Japanese emperors before him. Since the government announced the new gengo (imperial era name) shortly after Emperor Showa died on January 8, 1989, it was obvious that the selection had been made beforehand. But they still felt they had to wait until after he died to make the announcement. Because Akihito had already announced his abdication there was no need for such a consideration, and in order to help the citizenry make the change more smoothly, they decided to announce the new name before his abdication. While talking to people involved in the process of selecting the new gengo, the Mainichi discovered that Reiwa, the name eventually chosen, was not always an odds-on favorite. In fact, it wasn’t even on the initial shortlist.

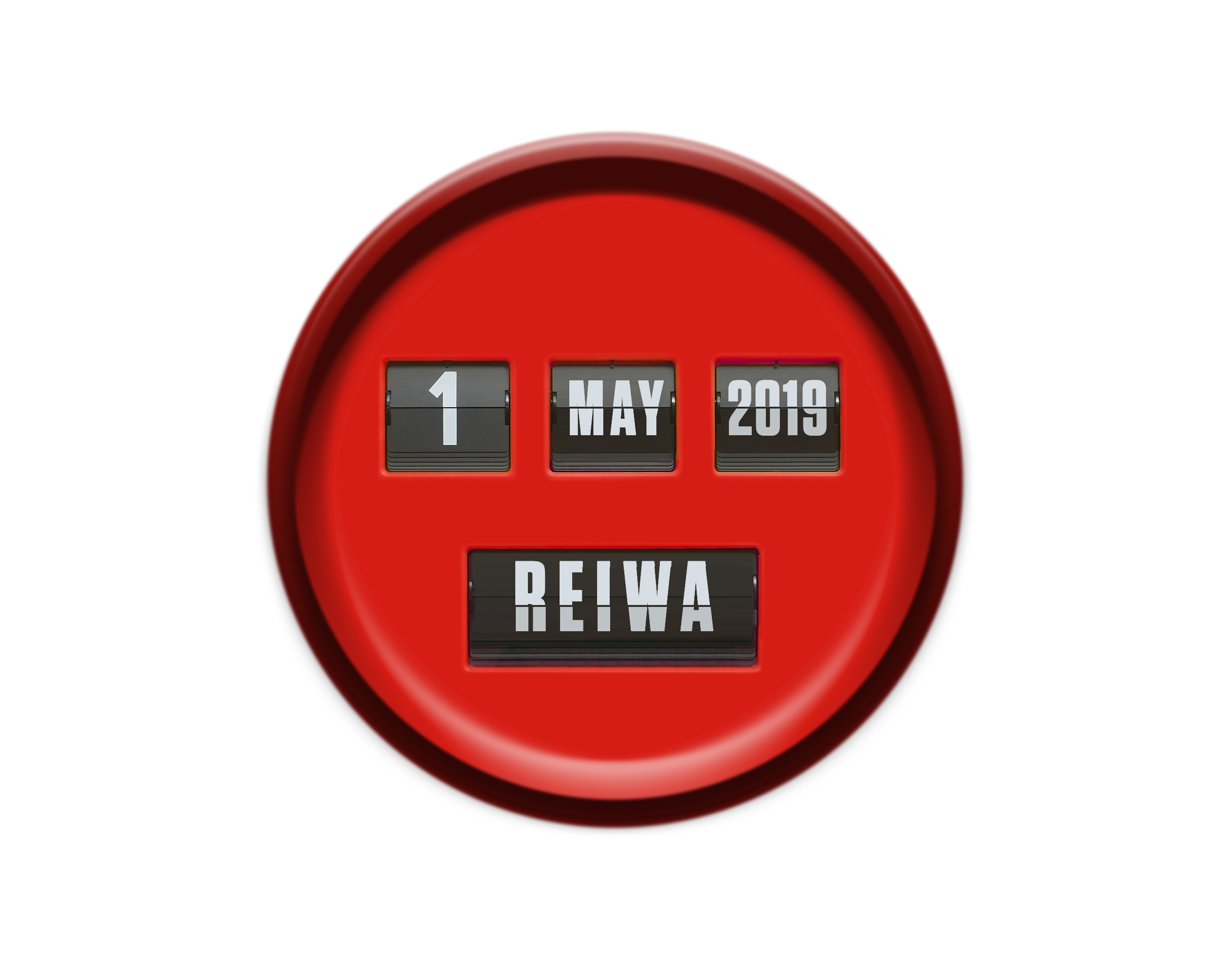

The then-chief cabinet secretary, Yoshihide Suga, revealed the new name on, of all days, April 1, 2019, one month before Akihito formally stepped down. A month earlier, the people who had been asked to come up with recommendations submitted them to the cabinet – meaning the then-prime minister, Shinzo Abe. The reason for the late submission was because Abe assumed the name chosen would leak, so he wanted to put off the selection as long as possible. The list handed to him by his staff contained about a dozen candidates, which were checked to make sure they hadn't been used before or weren’t trademarked or considered improper in any way. According to the Mainichi’s cabinet source, the favored gengo among the bureaucrats who compiled the list came from classical Chinese literature, which is the traditional source for gengo. The most promising selection was Banna, translated loosely as “world peace” and submitted by Tadahisa Ishikawa, the former president of Nishogakusha University. The term was taken from the Chinese book called Nishiki in Japanese, a source of much popular culture in Japan, including the best-selling manga The Kingdom. The panel thought the name Banna would therefore be easy to understand for most Japanese people.

However, Abe felt strongly that the source of the new era name should be purely Japanese, even though there was not much of a precedent for such a choice. With only one month to go before the scheduled announcement, the decision became more difficult, because Abe didn't like anything on the shortlist, so he asked the selection panel to submit new proposals. The Mainichi's source said that Reiwa was chosen just before the announcement was made. The word was taken from the Japanese volume of verse called Man'yoshu. In the context of representing a new imperial era, Reiwa refers to, in Abe's interpretation, the creation of a beautiful culture. In the end, the cabinet accepted the term, which means that it was almost single-handedly selected by Abe.

Almost four years have passed since the Reiwa announcement, which was met with some initial pushback connected to the literal reading of the two Chinese characters comprising the name, and which were interpreted to mean something along the lines of “peace and order by decree”, but the vast majority of Japanese citizens were fine with it. However, there was another aspect of the new gengo that was disputed in certain circles and which had nothing to do with the inferred meaning or source of the name, and that was the whole concept of identifying years by imperial reign.

Only days after Suga announced the new gengo, Jiji Press ran an article about ruling Liberal Democratic Party lawmaker Taro Kono, who at the time was foreign minister. Kono had already asked his staff to study the use of Western calendar years for all foreign ministry documents and dropping the use of gengo. A foreign ministry official said as much on April 1, 2019, when Suga announced the new name, clarifying that gengo would still be used for official internal documents related to budgetary matters and cabinet meetings. The next day, a senior bureaucrat in the prime minister’s office expressed outrage at the foreign ministry plan, describing it as “unbelievable”. Koichi Hagiuda, the LDP's secretary general at the time, criticized Kono, saying that he should “cherish” the use of gengo on all official documents.

The same day, Kono backtracked slightly, telling reporters that his idea would not lead to any significant changes, but that whenever the foreign ministry drew up documents to be shared with other governments, it was normal to use seireki, or Western calendar years. It was just common sense, he said, since gengo had no meaning to foreigners. In any case, there was no law that mandated the use of gengo for official documents, nor was there a standard in place for the application of either. Practically speaking, it took time and energy to change foreign documents that only used seireki into documents that only use gengo, and vice versa. He stressed that it wasn't his intention to eliminate the use of gengo. The purpose was simply to make the ministry's work more efficient.

If the controversy sparked by Kono's proposal seems overblown today, it's because it was. The bureaucrats and politicians who made a big deal out of it were currying favor with Abe, who they all knew had a personal stake in the matter. It had nothing to do with the practical application of gengo as Kono put forth, and, in any case, Western years would be used on those documents that were to be shared with foreign elements, with or without accompanying gengo. But Kono's point—that the gengo system is inherently inefficient and confusing—is a valid one, especially when addressing situations where spans of years involving multiple imperial reigns are involved. One cannot simply translate gengo into seireki without a complicated calculus that takes into consideration the different lengths of succeeding reigns, and even then there are special conditions that have to be accounted for. 1989, for example, is both the last year of Showa and the first year of Heisei. January 1 to January 7, 1989, is year 64 of the Showa Era, but the rest of 1989 is Heisei Gannen, the first year of Heisei.

The impracticality of the gengo system is most obvious in two realms - the study of history and financial documents, which still tend to use gengo. In an essay for the website Agora that appeared last January, financial designer Shinobu Naito explained his confusion over his repayment schedule for a housing loan he took out in Heisei 26, or 2014, when he bought a condominium. According to the plan he worked out with his bank, his final payment would be in September of Heisei 41, a date indicated on subsequent statements. When he took out the loan, the year Heisei 41 was entirely theoretical, because no one could predict how long Akihito would live or, for that matter, remain on the throne. When, in 2019, the Heisei era ended, the year Heisei 41 became an impossibility, and yet Naito's bank statements still incidated it as the year his loan would be paid off. Though it isn't that difficult to make the proper calculation to find out how many more years are left on his loan, he still needs to make that calculation. But why should he have to? As he points out, when Heisei ended, his statements started listing his new payments with Reiwa indications, but the Heisei 41 designation for his final scheduled payment remained, even though it was now an imaginary year. Wouldn't it just be more practical to use Western years? When he checked other banks' procedures he found that only one used seireki. Even passbooks use gengo.

This preference seems to be culturally mandated, since, as mentioned earlier, it isn’t legally codified. In 1979, or Showa 54 if you prefer, the Gengo Law was enacted by the Cabinet, but all it did was explain the process of selecting the gengo. Even Naito admits he thinks using gengo is “an important tradition for Japan”, but as an economist he views it as being inefficient and thinks that all documentation should include both gengo and seireki. Another problem, he points out, is for computer systems, which rely greatly on a unified system of dates. Programmers have to be very careful in creating files that overlap imperial reigns.

Our research reveals that since there is no law regarding gengo, most people don't have to use it. But if your organization or company does, that may mean you have to. Still, if you personally have something against gengo and you are asked to fill out a form you can cross out the gengo indication and write in the seireki. Civil servants presumably cannot, and some have gotten in trouble for not sticking to the plan. In March 1987 – Showa 62 – an education committee in Hiroshima Prefecture punished 54 high school principals under its administration because they had issued diplomas with seireki dates. Even if there is no national law mandating gengo, local governments can’t do as they please, and in Hiroshima Prefecture all official documents use gengo indications. It's the same with the national anthem. Though there is no law that actually states Kimigayo is Japan's national anthem and that people must do certain things when it is played, some local governments insist that civil servants stand and sing, regardless of the individual's personal beliefs.

As writers in English whose resources are all in Japanese, we often have to interpolate gengo into seireki, though, thankfully, most major media use Western years. (A notable exception is The Sankei Shimbun, which insists on gengo for almost everything). Way back in 1976, a government survey found that 87% of respondents said they “use gengo every day”, which doesn't necessarily mean they liked using it. But Showa was a long era, owing to how young Hirohito was when he assumed the throne, and thus didn't cause too much trouble. Also, in 1976 – or Showa 51 – everyone alive had only three gengo to deal with: Meiji, Taisho, and Showa. Now there are two more since Japan opened to the outside world in the late 19th century, and given the advanced age of the current emperor when he ascended the throne, there might be another one before too long. Under such circumstances, it's always advisable to have a calculator on hand.

Sources

Philip Brasor is a Tokyo-based writer who covers entertainment, the Japanese media, and money issues. He writes the Japan Media Watch column for The Number 1 Shimbun.