Issue:

November 2024

Weekly magazines respond in kind after Japanese boy stabbed to death in China

The September 18 killing of a Japanese primary school student in the affluent Nanshan district of Shenzhen in Guangdong Province, China, was the second incident of its kind this year. In the previous attack, on June 24 in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, a Japanese woman and her child suffered knife wounds after they were attacked with a knife as they walked to the local Japanese school. A Chinese bus attendant died after she attempted to stop the assailant, a 52-year-old unemployed man.

While not viewed as paragons of objective journalism, coverage of the slaying in Japan's weekly tabloids showed visceral reactions, with reportage more impassioned (and with less deference to political correctness) than seen in the national newspapers and wire services.

While the media has reported the child's hometown as Amagasaki, Hyogo Prefecture, coverage has refrained from identifying the victim and his parents, as well as his father's employer in China.

Needless to say, the weeklies, which don't operate bureaus in China or worry over a possible loss of advertisers, are less inclined to temper their generally negative slant on the Japan-China relationship. Follows are selected excerpts from four magazines.

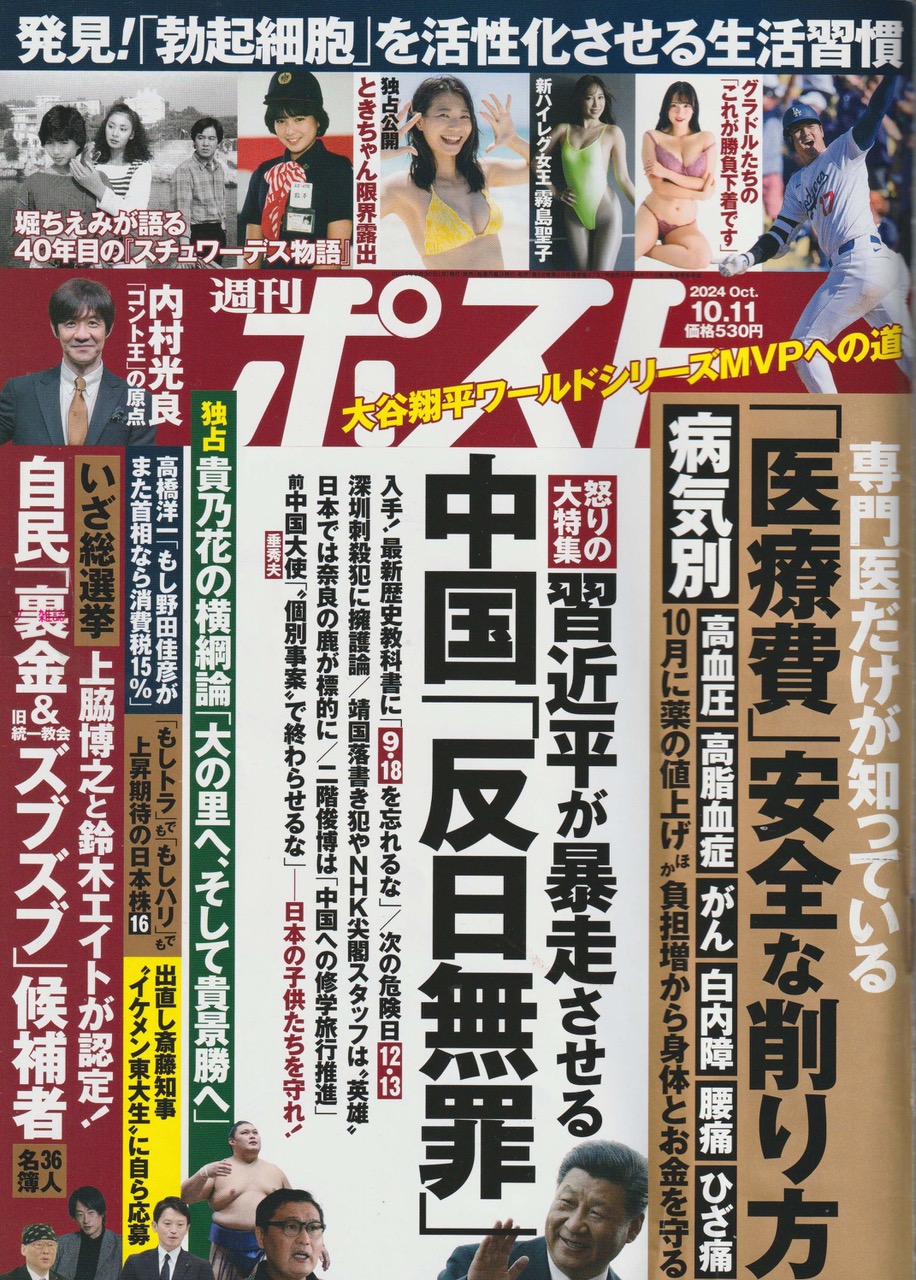

Hereafter I have translated all magazine headlines verbatim, beginning with Shukan Post (October 11), which read: Ikari no daitokushu: Shinsen nihonjin gakko no zangeki wa mata okurikaeseru / Shu Kinpei ga boso saseru / Chugoku 'hannichi muzai (Angry special feature: The tragedy at the Japanese school in Shenzhen will be repeated/ The anti-Japanese sentiment in China stirred up by Xi Jinping is not treated as a crime).

Shukan Post noted that the date of the Shenzhen slaying was regarded as one of China's “days of national shame,” in this case the anniversary of the Mukden Incident (also known as the Liutiaohu Incident) - a false flag event in 1931 staged by the Japanese Kwantung Army as a pretext for the invasion of Manchuria.

"Patriotic education began from the 1990s under President Jiang Zemin," said Kenta Takaguchi, a journalist now serving as guest professor at Chiba University. "It became increasingly strident, with some cities even sounding air raid sirens on September 18 to commemorate the date.

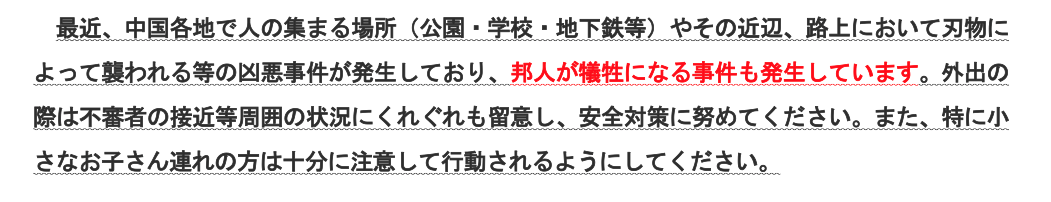

"Emails warning locally posted Japanese diplomats and workers at Japanese affiliated companies have also been issued," Takaguchi added. "A warning message to that effect was said to have been posted on September 18.

A 'safety handbook' posted on the Japanese embassy in Beijing's website stated: “There is a strong trend for anti-Japan sentiments to surface on dates of historic incidents in which Japanese were involved.”

Ref: https://www.cn.emb-japan.go.jp/files/100738364.pdf

Takaguchi noted that the next potentially dangerous date will be December 13, when the Nanjing Incident is memorialized.

"On that day in 1937, the Japanese army entered the city of Nanjing. In 2014 that date was established as a 'day of national mourning,’” he wrote, adding, “At present, Japanese in China are advised to take self-protective measures to avoid being identified as Japanese, such as having their children refrain from wearing randoseru (backpacks for schoolbooks) or speaking Japanese in public.

"What's more, between now and December 13, moves are afoot to send accompanying family members back to Japan.”

Asahi Geino (October 10): Chugoku ga shikakeru 'Hannichi senno kyoiku' no senritsu jittai (The truth behind the anti-Japanese brainwashing education instituted by China).

Unlike detailed coverage of the Shenzhen incident featured by other weeklies, Asahi Geino chose to focus on recent frictions between the two countries taking place in Japan, including an incident involving a Chinese broadcaster on NHK's Chinese-language news who affirmed China's claim to the Senkaku Islands (called Diaoyutai in Chinese) and men who fall into "honey traps" set by Chinese female intelligence operatives. It devoted the most space to recent cases of vandalism at Yasukuni shrine, where Japan’s war-dead are honored, including Class A war criminals.

The article noted that during the recent campaign for the presidency of the Liberal Democratic Party, lower house Diet member Sanae Takaichi had pledged that, if elected, she would continue paying visits to Yasukuni as prime minister.

Hiroshi Kawahara, head of Doketsusha, a right-wing nationalist group, told the magazine: “I have heard that some volunteers have been making determined efforts to guard Yasukuni shrine, but the government should take this matter seriously. Even with Japan's policy of separation of church and state, it doesn't change the fact that the shrine is sacred. As long as we cannot deny the possibility of such incidents continuing, proper security should be provided."

A special report in Spa (October 15-22) carried the headline: Chugoku de boso suru 'hannichi ojisan' no shozo (Portraits of anti-Japanese middle-aged men running rampant in China).

While the mainstream Chinese media described the September 18 Shenzhen killing as a “coincidence”, Tadasu Nishitani, a writer who specializes in China coverage, told Spa that the 44-year-old suspect belonged to a generation referred to in China as Ba-ling-hou (literally, "after eight-zero," i.e., people born after 1980). This period came shortly after the end of China's Cultural Revolution, after which the nation's economic growth underwent a sharp upswing. The Ba-ling-hou demographic reached the age of 30 in 2010 and 40 in 2020.

Over the past several years, however, this group's livelihoods have been severely affected by the collapse of the real estate bubble and business downturn caused by the Covid-19 pandemic among other factors.

"From this year, raised import duties on goods from China by the U.S. have resulted in many foreign companies to withdraw from China, exacerbating unemployment," journalist Zhou Laiyou told Spa. "To deflect criticism from the government, net users who post anti-Japanese contents aren't censored."

Masato Yoshikawa, operator of a startup business in Shenzhen, said: "Among China's netizens, people who do not necessarily embrace strong feelings post anti-Japanese content to attract attention.

“One recent example was the copying of postings on Chinese social media sites last May by a man who defaced the torii gate at Yasukuni with English graffiti.

"In many cases, the targeted viewers of nationalistic posts do not appear to be residents of cities, but those in regional cities or farming villages," Yoshikawa told the magazine.

Spa's reporter online search found "a remarkable variety of hits" for anti-Japan videos. Efforts to contact the posters directly for more information failed to elicit any responses, so the reporter directed an open question to one site, which carried a graphic showing China's national flag flying from the summit of Mt. Fuji.

"I am a Japanese," the reporter wrote. "Why did you post this image?" Over the two days that followed, the site was inundated with over 10,000 negative responses. Privately, however, he did receive a few messages to the effect that the writer "wanted to be friends with Japan".

"It was at this moment that I witnessed the frightening aspects of anti-Japanese mass psychology," the reporter wrote.

In a sidebar, Spa introduced a 36-year-old Japanese-language instructor, pseudonymously named Madoka Sawa, who has been teaching in China's Hebei Province for the past 13 years. "When I entered the classroom last April, the students seemed strangely silent," she said. "I turned toward the blackboard and was shocked to see writing in Chinese that asked, 'Was the polluted water tasty?'" (A reference to the release last year of treated water from the wrecked Fukushima Daichi nuclear power plant.) Sawa is currently pondering a return to Japan.

Finally, the headline in Shukan Shincho (Oct. 3) read: Chugoku Shinsen Nihonjindanji zansatsu no anbu(The dark side of the brutal murder of a Japanese boy in Shenzhen, China).

As an example of how anti-Japanese dogma permeates China's education system, a video posted in October 2023 showed students at a high school sports meet in Zaozhuang City, Shandong Province, performing a skit titled "The Assassination of Abe." The video showed the student in the role of Abe collapsing to the ground after two shots were fired, after which a banner was displayed reading, "The corpse began cooling after two shots were fired. The release of radioactive water into the sea will bring future catastrophes."

"Anti-Japanese education began from 1989, the year of the Tiananmen Incident, when Jiang Zemin headed the government," a commentator from China named Shi Ping, now a naturalized Japanese citizen who uses the name Seki Hei, told the magazine. "Common enmity with Japan was adopted to deflect criticism of the government and boost its domestic control. A manual the government distributes to teachers includes the requirement to provide instruction about the Nanjing Massacre and others in an emotional manner.

"It is common to see Japanese figures to assume the role of villains not only in cinema and TV dramas but more recently in computer games as well."

Tomoko Ako, a social researcher at the University of Tokyo, pointed out that many Chinese have become disaffected since the collapse of the real estate bubble and the subsequent rise in unemployment. "They're afraid to confront the Xi government or the Communist Party directly, so it's possible that anti-Japan education has been reinforced instead," Ako said. "Children have been made to feel they themselves have been attacked or victimized and end up believing that Japanese people are terrible."

Japan, the article concludes, needs to come up with better ways to get along with its yakkai na rinjin (bothersome neighbor).

Mark Schreiber is author of Shocking Crimes of Postwar Japan (Yenbooks, 1996) and The Dark Side: Infamous Japanese Crimes and Criminals (Kodansha International, 2001).