Issue:

July 2024

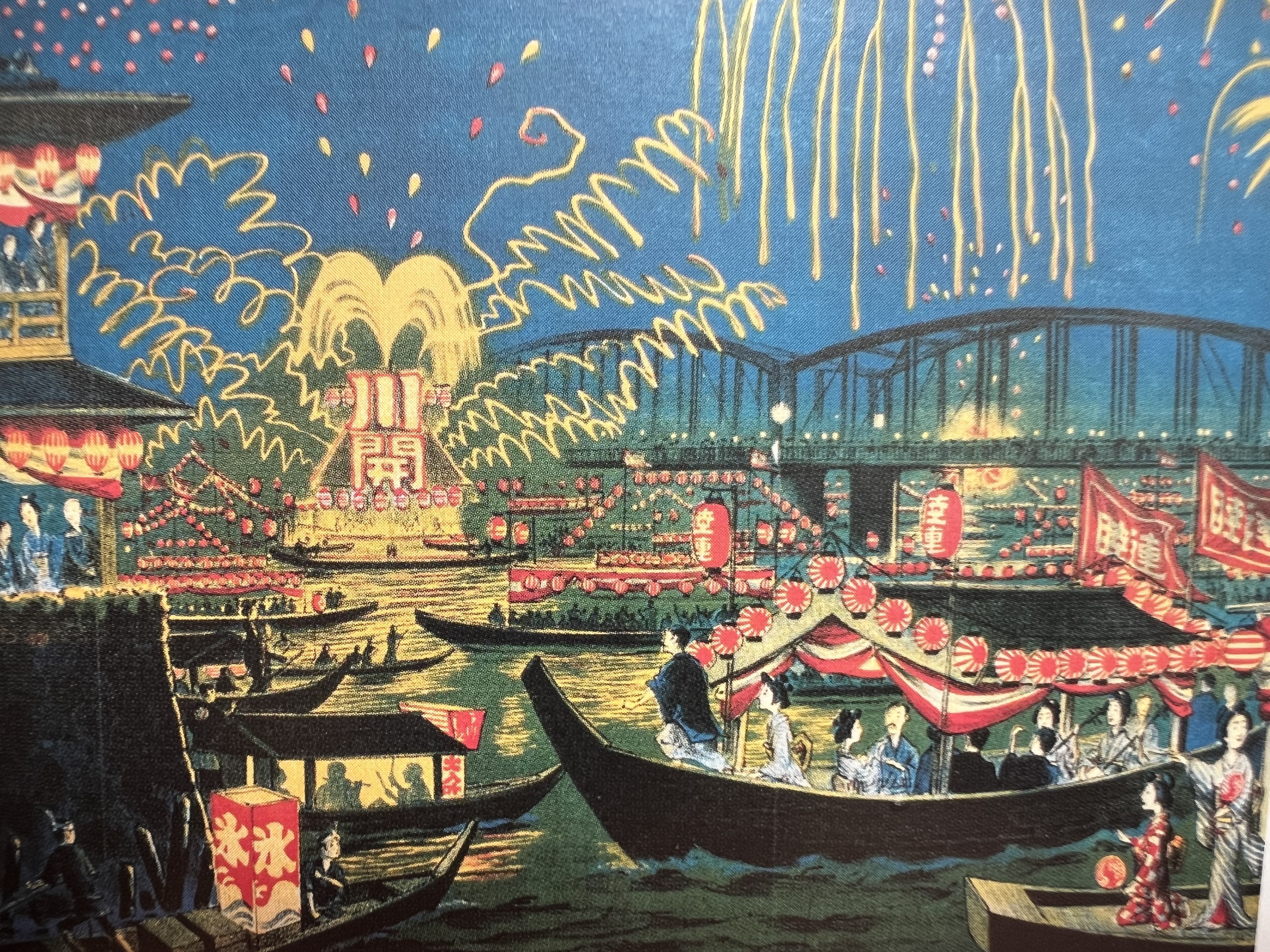

Tokyo’s summer fireworks festivals are extravaganzas of pyrotechnic brilliance

Boats already moved about on the Sumida River, and a number fitted with firework racks sat at midstream … and on every building rooftop, at each window, heads jostled with one another for space.

Fireworks, Yukio Mishima.

When I try to explain to Japanese people that November the 5th in Britain is Fireworks Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Night, I have their full attention. Its only when I get to the part about how, in my childhood, kids made newspaper-stuffed effigies of Fawkes, then burnt them on bonfires, that their faces begin to change. Even after I’ve explained that Guy Fawkes, a malcontent Catholic in Protestant England, was apprehended just moments before blowing up the Houses of Parliament in 1605, I sense a recoiling, as the annual reenactment of the plotter’s fate of being burnt at the stake, gets ranked alongside some of the more nauseous barbarities of the English table, such as toad-in-the-hole, bubble-and-squeak, and bread pudding.

When it comes to fireworks, Japan does things differently. Before it became a great annual event on the city’s cultural calendar, the kawabiraki (river opening) was conducted in the hope that it would cleanse the waterway of malign spirits responsible for the outbreak and spread of cholera. Although fireworks were introduced into Japan in 1613, the first official display was held in 1733, the year that famine and plague killed almost a million people nationwide. The shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune lit the fuse on the first firework. Following another exorcism tradition, the generalissimo released dozens of mukaebi (floating lights), believed to guide souls back to earth during the summer Obon festival.

Fireworks, along with moveable type printing, acupuncture, the compass, iron smelting, the abacus, and the wheelbarrow, were invented in China. Fireworks during the Edo period (1603-1868) were red. By the time Clara Whitney, the daughter of missionaries living in Tokyo during the Meiji era (1868-1912), observed the display, chemical flaming agents had been added. She described the river in her diary, as a setting “alive with lanterns of every colour and shape, and musical with the notes of the samisen”. Besides standard Roman candles and rockets were fireworks depicting “a Fuji, a lady, umbrellas, dogs, men, some characters, and other things, which I could not make out”. Whitney rightly noted the inseparable association of summer with watermelons, sake, and light yukata kimonos, elements that have not changed.

One of the most famous, and well-attended hanabi taikai (fireworks display), the Sumida River Fireworks Festival, will take place this year on July 27. The Tokyo police force claim the event is the worst day of the year for them – a logistical and security nightmare. As usual, bridges and lanes running down to the river will be sealed off, so that most visitors - there were over two million when I last attended the event - will have to be content to watch the night sky from roads running parallel to the river, or locate points further down the river. There are exceptions. Some attendees will have avoided the security entrapment by staking out plots along the river earlier in the day. Others, lucky enough to bag a dinner cruise aboard a yukatabune pleasure boat, will have the best appointed views of all. For considerably easier riverbank access, there are major displays through late July to early August on the Arakawa River, in Fuchu, and at the Edogawa Fireworks Festival.

Crackling with vitality and bravura, the thousands of fireworks create a visual experience that, for those lucky enough to attend, will endure far beyond the few precious moments that it takes for a rocket to climb the night sky, explode, and shower the river with streaks and sparks of molten light. The extravagance of burning things for pleasure might seem antithetical to the Japanese aesthetic of frugality, but the appreciation of fireworks is a subjective business. What appears to one viewer as tastefully understated may seem ostentatious to another. The appeal of names is equally subjective. Who is to say which of the following are in good or poor taste: Silver Garden, Five Flowers of the Ascending Yellow Dragon, Amber and Mercury Pavilion, or Pentachromic Necklace Fall?

Most people would agree, though, on the quiet beauty of senko-hanabi, one of Japan’s oldest fireworks. Its calm, understated appeal is similar to the attraction of the sparkler in the West, a firework that provides a respite from the grander, more heart-stopping displays. The origin of the name is disputed, but the most probable theory is that it refers to the Edo-period practice in Osaka for men to light incense sticks (senko), while passing their time with geisha on party boats moored on the Yodo River.

Perhaps the simplest senko-hanabi is the subote-botan, which is made from straw tipped with a dark, solidified powder. Wrapped and twisted inside a thin sheet of purple, yellow or green paper, the standard form appears in a somewhat modified version in the Kanto area where nagate-botan refer to a rather longer variety, whose lively sparks are said to resemble the peony (botan). The senses are further stimulated by the smell of pine smoke as the firework powder partly consists of charcoal made from aged pine trees. The nagate-botan is unusual in that it evolves in three distinct stages. When lit it bursts into flame, its ball of heat suggesting new birth and early childhood. Youth is represented at the next stage, when the sparks bloom and scatter like pine needles. The final moments, identified with old age and death, are when the sparks shrink and drop like chrysanthemum petals, a flower associated with graves and memorials.

Its doubtful whether young familes are quite so clued into the symbolism of senko-hanabi, but, judging from the faces of their kids, these slim, hand-held fireworks have the power to upstage even the summer’s grandest pyrotechnic extravaganzas.

Stephen Mansfield is a Japan-based writer and photographer, whose work has appeared in more than 60 magazines, newspapers and journals worldwide. He is the author of 20 books.