Issue:

November 2024 | Book Extract

HOSTESSES

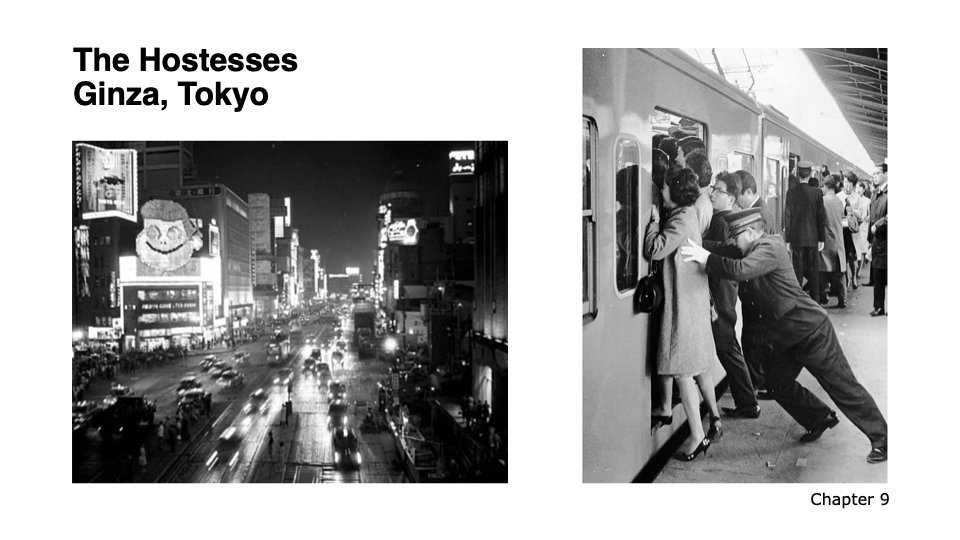

NIGHTCLUB HOSTESSES have a long tradition in Japan, originating in the world of the geisha house—a richly colorful social institution, centuries old, where graceful kimono-clad women, trained from childhood in the art of music, dance and subtle praise, entertained well-to-do men of high social standing behind closed doors. The modern-day hostess club has evolved as a more egalitarian and Westernized form of nighttime amusement—one that did not demand the hard apprenticeship and unyielding servitude that geisha were subjected to—and one that was also more accessible for the common man.

Hostess bars have flourished in Japan primarily because of the highly demanding Japanese business culture, which, especially in the postwar era, has required salarymen to work brutally long hours and display strict obeisance to authoritarian bosses. Japanese employees need to work off stress before heading home on long crowded commutes to the wife and kids and a tiny, cramped apartment. One good way to do it, the reasoning goes, is to spend a couple of hours in the company of a friendly, attractive young lady skilled in the art of flattery. Also, corporate executives need a venue to impress their clients. This is where higher-end clubs with their glamorous hostesses came in.

It is a modus operandi that distinguishes Japan from the US. Whereas in the West, it has largely been the quality of the product and its price that are important in sales and marketing, in Japan it has long been the case that personal relationships are equally vital, if not paramount. Indeed, that is why the majority of bar tabs have been put on company expense accounts and, why the total amount spent annually by Japanese business on “entertainment” has often been more than the entire national defense budget.

Contrary to popular belief, though, Japanese nightclub hostesses do not automatically sleep with their customers. Indeed, in the better clubs in Japan, hostessing at its best is a highly refined Japanese art, requiring patience, a willingness to listen raptly to men complain about their jobs, to laugh at their stupid (often sexist) jokes and, on occasion, to carry on an intelligent conversation on a variety of topics ranging from the state of the economy to sports. Looking one’s best is also a must, which means enduring daily trips to the beauty parlor, regularly purchasing new wardrobes at expensive boutiques and making an occasional visit to the plastic surgeon.

“We are far from being common prostitutes,” said one Ginza hostess, describing her chosen profession. “Our task is to flatter, to provide attention, to pamper. Our job requires a certain amount of art. Japanese men have a tough corporate life. They have to work hard. There is a lot of stress. We try to provide a kind of nursery service, so they can revert to childhood. We’re more like child psychologists than anything else.”

Or, as a middle-aged Tokyo geisha once put it to the New York Times, referring to the same MO: “It may sound impolite to wives, but men have a world that wives cannot understand. Men release their inner self in a place like this and then go home. Professional women can draw out a man’s inner self, but it requires experience. There is a technique to good listening.”

THE APALON

One of the most famous, most elegant, most exclusive and most expensive clubs in Japan during the seventies and eighties was the Apalon on the Ginza. It featured rugs made of polar bear hide, deep cushioned sofas covered with tiger skins and a bevy of the most beautiful and gracious women in the city.

The Apalon’s exclusively Japanese clientele included some of the most important people in Japan in the latter part of the twentieth century: Liberal Democratic Party kingpin Kakuei Tanaka, multi-billionaire Yoshiaki Tsutsumi, famed actor Shintaro Katsu and others who thought nothing of dropping ten thousand dollars a night on food and drink and female companionship.

The owner was one Akira Shimizu, a short, cognac-drinking, Marlboro-smoking man, who was nicknamed “The General” because he always stood at the bar, drink in hand, every evening, vigilantly watching everything that went on in his club. Subtle eye signs and hand gestures, as sophisticated as those of the third base coach for the Yomiuri Giants, would inform his charges when it was time to order another round, to rotate to another table in order to “create a fresh feeling” for the guests, or to convey some other critical instruction like padding the bill for particularly obnoxious customers to make sure they would never come back.

To Apalon aficionados, places like the supposedly elite Copacabana or the nearby Mikado with its 1,200 numbered hostesses and pagers in bras, were lower class because it was easy to spend the night with the girls. All that was required was a lot of money. The Apalon clientele preferred the psychological game that their club offered, one in which a love affair, not just sex necessarily, was the end goal—this, even though a night at that club would bankrupt normal men. It was the excitement of the chase that appealed to them.

There was an aspect at play here that sociologists and Japanologists had long commented on, a pattern of dependent servitude in family life where mothers devoted themselves so intensely to their male offspring’s child’s care that when the son grew up, he was unable to relate to his own spouse as an equal partner in love—especially after his own children were born. (It was this same psychology that would later drive wealthy Japanese men to patronize certain exclusive clubs which allowed them to don diapers and regress to early childhood, sucking at the breast of a professional mother figure. Seriously.)

Although being a nightclub hostess in Japan offered more im- mediate material rewards than a job in the corporate world—an overwhelmingly male-dominated preserve where most women were relegated to serving tea, licking stamps and waiting for Mr. Right to come along—it also had its downside.

Said a longtime Ginza “mama”—as the women who manage hostesses and geisha are known—speaking on condition of anonymity, “Nightclub mamas in Tokyo are notoriously neurotic, especially those who’ve been around for twenty years. Far from learning how to ‘really listen,’ you become mentally deranged. You get tired of having to cater to people all the time. It’s such an emotionally hard, boring job that no one wants to do it forever. After a while you stop remembering your customers names. It’s all one big blur.”

If being a hostess posed strains for Japanese girls who, one might say, were culturally attuned to such subservient behavior given Japan’s reputation as a bastion of male chauvinism, it would go with- out saying that Western women would be even more taxed, given their independent and opinionated ways and, their comparative lack of interest in nurturing the male ego.

The Apalon’s Shimizu, for example, quit hiring foreign hostesses after an experimental trial period because he knew that sooner or later he would have to fire them for one or more violations of his code of conduct, the most common of which were an inability to keep the Japanese customers’ names straight or remembering their favorite whiskey. He was once quoted as saying that “Putting a Western girl in a club like mine is like serving cheap wine at an imperial banquet.”

There were lesser, if still expensive clubs, in the nighttime entertainment business (or mizu shobai, literally “the water trade,” as it is called in Japanese) and one could more easily find foreign hostesses there. The clubs wanted them because they believed that Caucasian women would reel in curious Japanese customers, who seldom had a chance to meet foreign women. And the girls liked the idea of the big money the clubs were willing to pay them to sit with an customer and pour his drinks—even if they found the work itself unbearably monotonous.

The attitude of a California girl known simply as Karina, a part time student, was typical. In a newspaper interview with an American journalist some years ago, she said that being a hostess in Japan was the most boring job in the world. “They’d ask you the same pat questions,” she complained, “and make the same pat remarks: Where are you from? What’s the weather like in America? Did you know Japan has four seasons? A guy would get a few drinks in him, and he would turn red, like a traffic stoplight, and the sweet personality would disappear. He’d start singing songs off key and running his hands up and down my body, making crude jokes about the size of my breasts. The muscles in my mouth ached from having to smile so much, from having to pretend to laugh so much at the stupid jokes.”

Karina, like so many other Western women, could not quite grasp the Japanese concept that, good or bad, that was the way it was supposed to be.

Robert Whiting is a best-selling author and journalist who has written several successful books on sport and contemporary Japanese culture, including You Gotta Have Wa (1989), The Meaning of Ichiro (2004) and Tokyo Junkie (2021).