Issue:

Ayako Mie asks the perennial question: “So you want to belong to a kisha club?”

I have a confession to make. I’m a regular member of the prime minister’s kisha kurabu and an associate member of the Diet kisha kurabu, with all of what might be called the perquisites that go with it. In other words, I get to attend the regular press conferences where I and the other reporters have a chance to grill ranking members of both the ruling and the opposition camps and sometimes have a casual chat with lawmakers.

I know that freelance journalists and reporters affiliated with non Japanese media are often not eligible or have a hard time getting membership in the “establishment,” and they often cry foul as they are denied access to first hand information and reporting opportunities.

I’ve heard the kisha clubs described as the “root of all of journalism’s evils” as well as a “hot bed for collusive relationships” between the Japanese media and politicians due to its closed nature. But, after five months as a member of this “elite” group of Japanese press corps, I’m kind of disappointed; I’d have to say that the power of the kisha clubs is far more myth than reality.

What’s said in the press club confines does not often consist of, or lead to critical information, because ranking officials only repeat what’s already out. Some people might disagree with me, believing that they would do a far better job than the press club reporters in prying knowledge from the tight lips of the politicians. But I’ll remind you of something that I’m sure you already know: like any country, it is the personal relationships with your sources that will eventually lead to the tip of iceberg.

And that is the hardest part of covering Japanese politics because building such relationships costs money, takes human resources and time, as well as experience and teamwork.

I (and most of my foreign colleagues, I believe) can’t compete, for example, with the ban kisha reporters of the Japanese media, who are embedded so deeply with the prime minister and other political heavyweights that they follow them around all day long, everywhere from the bathroom to costly overseas trips.

But that’s how they thaw the ice with politicians. That’s how they get the chance to booze with them and belt out some memorable late night karaoke favorite. That’s how they get them to remember who they are.

Can I afford to spend every day chasing one person hoping that he will give me an exclusive some day? Am I prepared to pay visits to a source really late at night or early in the morning for the sake of getting one piece of a document a few hours before my competition?

It’s a dilemma that I face every day, which sometimes leads to anxiety attacks. Despite the fact I love reporting politics and remain fascinated by it, I’ll never have the same amount of information that was collected by the infantry battalion of NHK reporters next to me. I cover both the ruling and the opposition camps alone while other Japanese media have dozens on the same beat.

And unless cloning becomes a reasonable possibility for a poor journalist, I’ll never be able to spend enough time with one ranking lawmaker to forge a good relationship, even though I make sure to pay courtesy visits to the lawmakers I become acquainted with, and never turn down any invitations for gatherings.

Am I the one whining now? I suppose a little bit. So I remind myself that good reporters are always walking a fine line between being an insider and a very talented investigative reporter.

I tell myself to remember the journalists who excelled in investigative journalism without being a member of the kisha club, like Takashi Tachibana, the prominent journalist who broke the stories about the bankroll politics that led to Kakuei Tanaka’s downfall.

I tell myself the universal fact that one does not need the kisha club if one is really good at building sources and has excellent news judgment and good hunches.

And finally, I remind myself that my job is not covering incremental stories but reporting on the big picture, and helping demystify the complicated Japanese political system for non Japanese readers. Since that requires monitoring daily developments, as everything is connected in Japanese politics, camping out at the kisha club or having access to the Diet building helps.

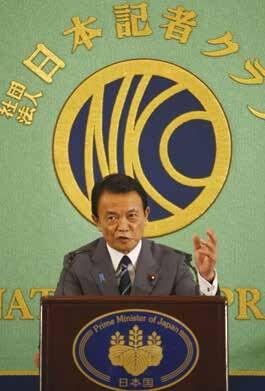

Even with my coveted membership, however, I am occasionally confronted with the disappointingly closed nature of political reporting in Japan. Just the other day, I got a call from the office of the Ikokai group, the habatsu or faction of Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso, who also doubles as the finance minister.

They wanted to let me know that I was not invited to their upcoming dinner gathering, because I or to be more specific, my newspaper, the Japan Times was not a regular member of the Diet kisha club. Nor, as I was surely aware, was I the Aso faction’s ban kisha. They were clearly letting me know that even within the kisha club, there is a hierarchy: regular members, followed by associate members.

So I missed one good opportunity to get acquainted with the LDP politicians. But am I going to let it affect my pursuit of good journalism? I don’t think so.

Ayako Mie is a staff writer covering politics for the Japan Times.