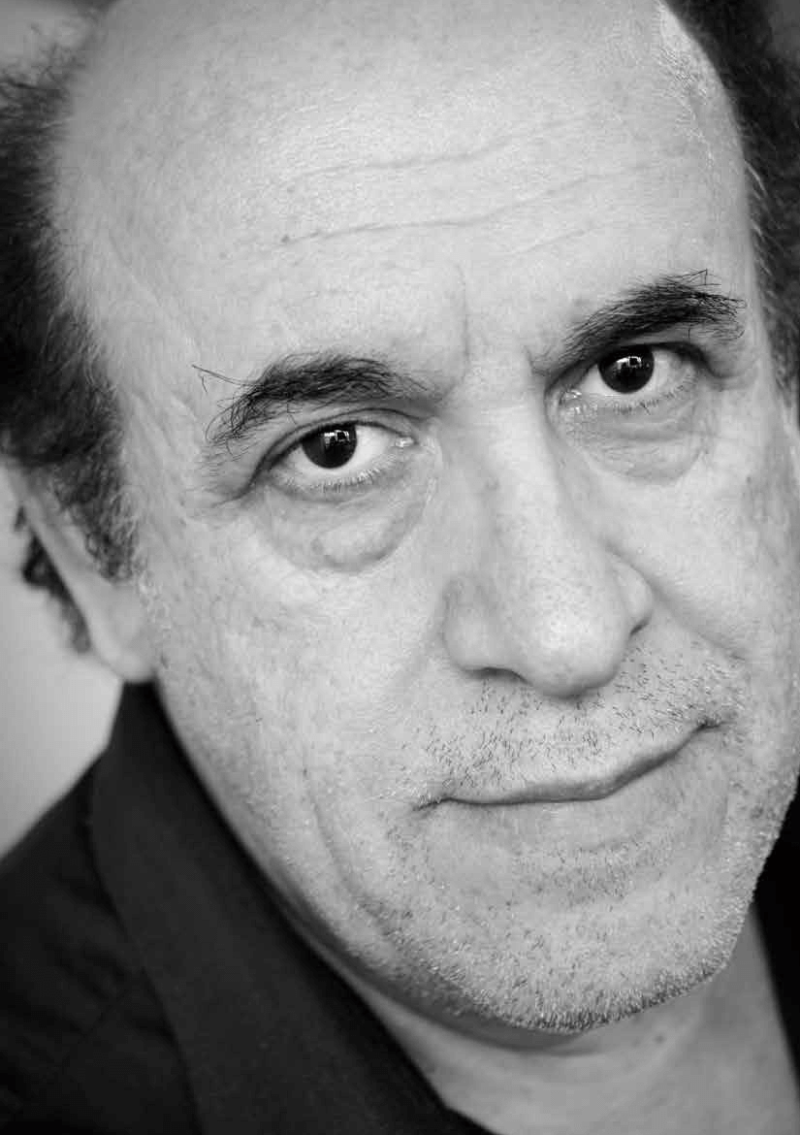

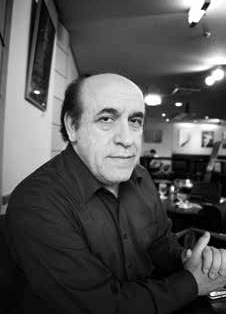

Issue:

Syrian Khaldon Azhari’s early years were the essence of the Dickensian term, “the best of times and the worst of times.” He was born to an intellectual family in what is now the warravaged town of Homs. His father, Mohammad Azhari, was a journalist and owner of a daily newspaper, in a world where reality could turn upside down anytime with the change of the regime. And change was frequent: only short intervals separated coups d’étattoppling governments. Managing the newspaper meant his father always had to walk a tightrope, unaware of what the future was holding for the country and for his family. In 1968, he lost ownership of the newspaper when it, and all the other dailies, was seized by the government.

However, this shocking twist of fate did not deter young Khaldon from cherishing the dream of becoming a journalist like his father. He saw the determination that the vocation demands as well as the high level of satisfaction from conveying a message to one’s readership. His family, on the other hand, was firmly against him choosing the vocation that proved so harsh to his father. Instead, Khaldon was sent to pursue higher studies in petrochemical engineering, which his mother thought would ensure a steady source of income without the mental agony that his father had to endure. But after getting a university degree in petrochemical engineering, he remembered the joy of writing.

“When I was in elementary school, my father helped me write essays on different subjects, which silently planted in my mind the seeds of love for playing with words. Then I started to help my father write news fillers and other items for his paper.” During those early years he particularly enjoyed compiling Arabic crosswords. Through the popularity of the crossword section, his name became known to newspapers subscribers in his hometown.

“My father was a pan Arab nationalist and suffered through the years of regimeimposed strict censorship. He was in and out of prison, but never gave up the profession, despite the lack of material reward. Over the course of time, I learned the art of walking through the minefield of news making.” Though it was not easy to be a journalist in a country where everything was controlled and supervised, he was soon writing a regular column in the university student newspaper and also started taking photos. This drew the attention of the editor of his home town’s main newspaper, who approached him to write for the daily.

“It started well, but after the editor in chief was replaced, the new editor did not like my writing and transferred me from the political division to the city life section. Although my articles were popular, the new boss fired me from the newspaper.” Not everyone in the family was unhappy with the outcome. His father by then had already passed away; his mother held a party to celebrate the return of her son from the uncertain world of journalism.

‘MY FATHER SUFFERED THROUGH THE YEARS OF STRICT CENSORSHIP . . . OVER TIME, I LEARNED THE ART OF WALKING THROUGH THE MINEFIELD OF NEWS MAKING.’

With that sad episode, Khaldon came to the bitter realization that his country was not a place for a journalistic career. He briefly went back to university, but “the future was turning bleak and I wanted to see the world.” After returning from a visit to Italy, he found a job in the ministry of tourism. After working in Lebanon, and traveling to the U.S., a twist of fate brought him to Japan, where he found himself once again in the world of journalism. He has stayed in the country since.

“My earlier encounters with journalism still fascinated me so I was always looking for an opening to return. In Japan I got an offer to work as a journalist in the press section of the embassy of Oman. It was in the early 1990s, a time when Japan was becoming more interested in the Arab world.”

He left the embassy in 1998 to get more involved in mainstream journalism, realizing that he could work independently to feed the Arab press with news and analytical pieces on Japan. He established the K A News company and began providing news services to a number of Arab countries. In 2006 he established Pan Orient News in the U.S. with a branch office in Tokyo. Currently he covers Japan for Petra News Agency of Jordan and also feeds UAE News Agency with Japan content. In addition, he writes for the Qatar based daily Al Sharq, and works as a commentator for Radio Cairo and Saudi TV. His media outlets cover a number of Arab countries, but his homeland is absent. “I’m a Syrian journalist in Japan, but I don’t report for any Syrian media. It’s because the Syrian media is part of the government and you need to belong in order to report.”

As a journalist with such diverse experiences and a life marked by attacks on press freedoms, Khaldon has a clear view of his country’s present crisis and what could have prevented it. “In Syria there was a need for reform, a need for freedom of expression and diversified newspaper ownership. If we had only had a free media, we would definitely have had a better chance of avoiding the disaster that we are embroiled in now.”

Monzurul Huq represents the largest-circulation Bangladeshi national daily, Prothom Alo. He was FCCJ president from 2009 to 2010.