Issue:

January 2022

Taro Kono’s reign as the LDP’s media chief has got off to a mixed start

If you asked foreign correspondents in Japan which Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) politician they like best, quite a few of them would answer Taro Kono, or, as the man himself prefers, Kono Taro.

Why? He is fluent in English and has held several press conferences at the FCCJ. He appears more liberal than many of his party colleagues and wants to reform the way things are done at the government level in Japan. He has a good understanding of young people and foreign residents, is aware of the major problems confronting Japanese society, and is very active on Twitter and YouTube. Last, but not least, he has a sense of humor.

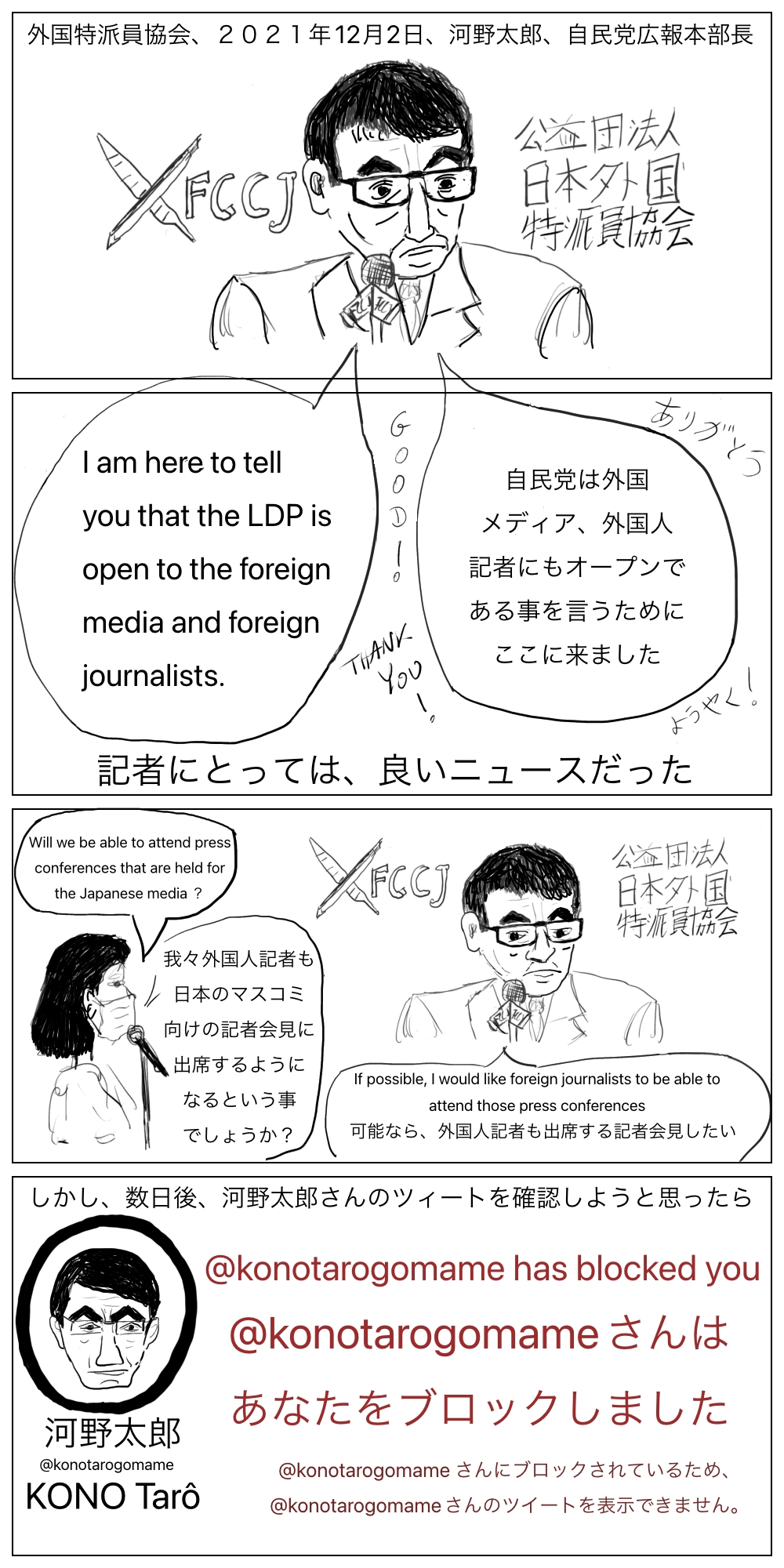

I attended several of Kono's press conferences, along with colleagues from the Japanese media, and was able to ask a number of questions when he was in charge of Japan’s Covid-19 vaccination rollout. So, naturally, I was pleased when, after being appointed the LDP’s public relation boss, he told FCCJ members on December 2 that he was “here to tell you LDP is open to the foreign media and foreign journalists”. I believed him. After all, he had given partial – and polite – answers to my three questions. I thought he was sincere, even though I also remembered that he had categorically refused to answer several questions when he was foreign minister.

That said, I was happy to learn that he would be doing everything possible to grant me and other foreign journalists better access to figures in the LDP. My optimism was short-lived. Just days after his appearance at the FCCJ, I discovered that his Japanese-language Twitter account had blocked me. I was incredibly disappointed.

Kono, however, is widely known to block people on Twitter. He was questioned a couple of times about this, and replied that he blocks people who post negative or otherwise unpleasant comments so that his followers don’t have to read them. Twitter, though, retains users’ comments on someone’s posts even after they have been blocked.

While I understand why he might want to block people who post outrageous comments, he had absolutely no reason to block me. I have never posted anything bad about him. On the contrary. During the FCCJ press conference, I posted in French on Twitter that Kono had voiced support for foreign students who were unable to enter Japan due to pandemic-related travel restrictions. I saw his support for them as a positive thing. But even if I had said something negative, this would not have justified his decision to block me. Before blocking someone on Twitter, it’s a good idea to find out more about the person you perceive as being unfairly critical or negative.

As the public relations boss of Japan’s ruling party, blocking a journalist also means denying that journalist access to a potentially important source of information, since politicians now sometimes use Twitter to make policy announcements.

In response, I sent Kono a direct message via his English-language account and posted a manga about him on Twitter. Fortunately, it did the trick. About two days later, he unblocked me.

The episode reminded me that as journalists, we should be careful about forming opinions of people – especially politicians - based on first impressions, and keep a professional distance. The raison d’etre of politicians is to get elected, then re-elected and, for some, to become prime minister. That is exactly what is expected of Kono. When he opens the door to us, we should be aware that it is probably because he thinks it is good for him and his supporters inside the LDP.

Kono’s book, which I read before the LDP leadership election last September, gave me a better insight into what kind of politician he is. A large part of the book is about him and what he did (mainly successfully) in the past. That is interesting, but it does not tell us much about how he would change Japan if he ever became prime minister.

He offers plenty of examples of what should be reformed, and how, but his focus is on administration, systems, equipment, methods and technology, not on people. As I read, I frequently asked myself where the references to people were, aside from those to himself and his father. I could apply the same criticism to the winner of the LDP presidential election, Fumio Kishida, whose December 2020 book, Kishida’s Vision, I also read.

Even if Kono is sincere about wanting to reform, change, abolish and transform so that Japan falls in line with international standards, he is ultimately steeped in the culture of the Japanese political system.

When I asked him what he thought about the kisha clubs, he did not answer directly but explained that some LDP’s press conference were organized by Hirakawa kisha club and, as a result, he did not have the authority to force it to accept foreign journalists.

I asked Kono why the clubs wield so much power? He did not answer. Instead, he seemed to accept it as a fact of life. And given their influence, it makes sense for ambitious politicians like Kono to prioritize major Japanese media organizations.

Let’s see how the LDP treats the foreign media in the coming months. I hope I will soon be able to post another manga depicting foreign correspondents freely asking questions at LDP press conferences, without fear of being blocked on social media.

Karyn Nishimura is a correspondent for the French daily newspaper Libération and Radio France.