Issue:

The Wall Street Journal is preparing its journalists to detect deepfakes, a job that is increasingly difficult thanks to advances in AI

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IS FUELING the next phase of misinformation. The new type of synthetic media known as deepfakes poses major challenges for newsrooms when it comes to verification.

The Wall Street Journal is taking this threat seriously and has launched an internal deepfakes task force led by the Ethics & Standards and the Research & Development teams. This group, the WSJ Media Forensics Committee, is comprised of video, photo, visuals, research, platform, and news editors who have been trained in deepfake detection. Beyond this core effort, we’re hosting training seminars with reporters, developing newsroom guides, and collaborating with academic institutions such as Cornell Tech to identify ways technology can be used to combat this problem.

“Raising awareness in the newsroom about the latest technology is critical,” said Christine Glancey, a deputy editor on the Ethics & Standards team who spearheaded the forensics committee. “We don’t know where future deepfakes might surface so we want all eyes watching out for disinformation.”

The production of most deepfakes is based on a machine learning technique called “generative adversarial networks,” or GANs. This approach can be used by forgers to swap the faces of two people for example, those of a politician and an actor. The algorithm looks for instances where both individuals showcase similar expressions and facial positioning, then look for the best matches in the background to juxtapose both faces.

Because research about GANs and other approaches to machine learning is publicly available, the ability to generate deepfakes is spreading. Open source software already enables anyone with some technical knowledge and a powerful enough graphics card to create a deepfake.

DEEPFAKE CREATORS CAN USE a variety of techniques. Faceswap is an algorithm that can seamlessly insert the face of a person into a target video. This technique could be used to place a person’s face on an actor’s body and put them in situations that they were never really in. Forgers can also graft a lip syncing mouth onto someone else’s face, transfer facial expressions from one person into another video, making them seem disgusted, angry, or surprised or even transfer the body movements of a person in a source video to a person in a target video.

Journalists have an important role in informing the public about the dangers and challenges of artificial intelligence technology. Reporting on these issues is a way to raise awareness and inform the public.

“We want all eyes watching out for disinformation.”

“There are technical ways to check if the footage has been altered, such as going through it frame by frame in a video editing program to look for any unnatural shapes and added elements, or doing a reverse image search,” said Natalia V. Osipova, a senior video journalist at the Journal. But the best option is often traditional reporting: “Reach out to the source and the subject directly, and use your editorial judgment.”

If someone has sent in suspicious footage, a good first step is to try to contact the source. How did that person obtain it? Where and when was it filmed? Getting as much information as possible, asking for further proof of the claims, and then verifying is key.

If the video is online and the uploader is unknown, other questions are worth exploring: Who allegedly filmed the footage? Who published and shared it, and with whom? Checking the metadata of the video or image with tools like InVID or other metadata viewers can provide answers.

IN ADDITION TO GOING through this process internally, the Journal collaborates with content verification organizations such as Storyful and the Associated Press. This is a fast moving landscape with emerging solutions appearing regularly in the market. For example, new tools including TruePic and Serelay use blockchain to authenticate photos. Regardless of the technology used, the humans in the newsroom are at the center of the process.

“Technology alone will not solve the problem,” said Rajiv Pant, chief technology officer at the Journal. “The way to combat deepfakes is to augment humans with artificial intelligence tools.”

Deepfakes are often based on footage that is already available online. Reverse image search engines like Tineye or Google Image Search are useful to find possible older versions of the video to suss out whether an aspect of it was manipulated.

Editing programs like Final Cut enable journalists to slow footage down, zoom the image, and look at it frame by frame or pause multiple times. This helps reveal obvious glitches: glimmering and fuzziness around the mouth or face, unnatural lighting or movements, and differences between skin tones are telltale signs of a deepfake.

In addition to these facial details, there might also be small edits in the foreground or background of the footage. Does it seem like an object was inserted or deleted into a scene that might change the context of the video (e.g. a weapon, a symbol, a person, etc.)? Again, glimmering, fuzziness, and unnatural light can be indicators of faked footage.

In the case of audio, listen for unnatural intonation, irregular breathing, metallic sounding voices and obvious edits, all hints that the audio may have been generated by artificial intelligence. However, it’s important to note that image artifacts, glitches, and imperfections can also be introduced by video compression. That’s why it is sometimes hard to conclusively determine whether a video has been forged or not.

A NUMBER OF COMPANIES are creating technologies often for innocuous reasons that nonetheless could eventually end up being used to create deepfakes. Adobe is working on Project Cloak, an experimental tool for object removal in video, which makes it easy for users to take people or other details out of the footage. The product could be helpful in motion picture editing. But some experts think that micro edits like these the removal of small details in a video might be even more dangerous than blatant fakes since they are harder to spot.

There are algorithms for image translation that enable the altering of weather or time of day in a video. These could be helpful for post production of movie scenes shot during days with different weather. But it could be problematic for newsrooms and others, because in order to verify footage and narrow down when videos were filmed, it is common to examine the time of day, weather, position of the sun, and other indicators for clues to inconsistencies.

Audio files can also be manipulated automatically: One company, Lyrebird, creates artificial voices based on audio samples of real people. One minute of audio recordings is enough to generate an entire digital replica that can say any sentence the user types into the system.

While these techniques can be used to significantly lower costs of movie, gaming, and entertainment production, they represent a risk for news media as well as society more broadly. For example, fake videos could place politicians in meetings with foreign agents or even show soldiers committing crimes against civilians. False audio could make it seem like government officials are privately planning attacks against other nations.

“We know deepfakes and other image manipulations are effective and can have immediate repercussions,” said Roy Azoulay, founder and CEO of Serelay, a platform that enables publishers to protect their content against forgeries. “We need to really watch when they become cheap, because cheap and effective drives diffusion.”

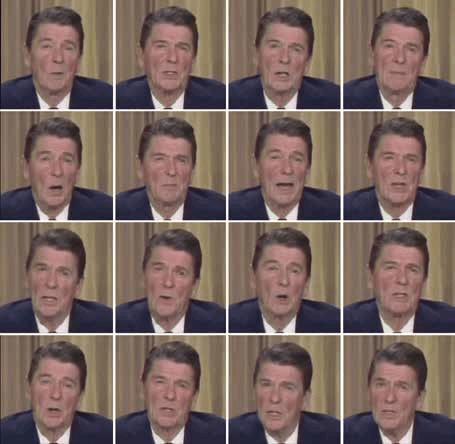

Screen grabs from an original and an altered video. The second and fourth column are stills from the original. The first and third columns have had Barack Obama’s facial movements mapped on to ex-president Ronald Reagan’s. The video is on the Nieman Journalism Lab site here: https://bit.ly/2zZxqH8

Publishing an unverified fake video in a news story could stain a newsroom’s reputation and ultimately lead to the public losing trust in media institutions. Another danger for journalists: personal deepfake attacks showing news professionals in compromising situations or altering facts again aimed at discrediting or intimidating them.

As deepfakes make their way into social media, their spread will likely follow the same pattern as other fake news stories. In an MIT study investigating the diffusion of false content on Twitter published between 2006 and 2017, researchers found that “falsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than truth in all categories of information.” False stories were 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than the truth and reached 1,500 people six times more quickly than accurate articles.

Deepfakes are not going away anytime soon. It’s safe to say that these elaborate forgeries will make verifying media harder, and this challenge could become more difficult over time.

“We have seen this rapid rise in deep learning technology and the question is: Is that going to keep going, or is it plateauing? What’s going to happen next?” said Hany Farid, a photo forensics expert. “I think that the issues are coming to a head,” he said, adding that the next 18 months leading up to the 2020 election will be crucial.

Despite the current uncertainty, newsrooms can and should follow the evolution of this threat by conducting research, partnering with academic institutions, and training their journalists how to leverage new tools.

Francesco Marconi is R&D chief at the Wall Street Journal. Till Daldrup is a research fellow at the Journal and a master’s candidate at NYU’s Studio 20 journalism program. This article originally appeared on the NiemanLab website and is used with permission.