Issue:

November 2024

Remembering Yukio Mishima and his brand of ugly nationalism

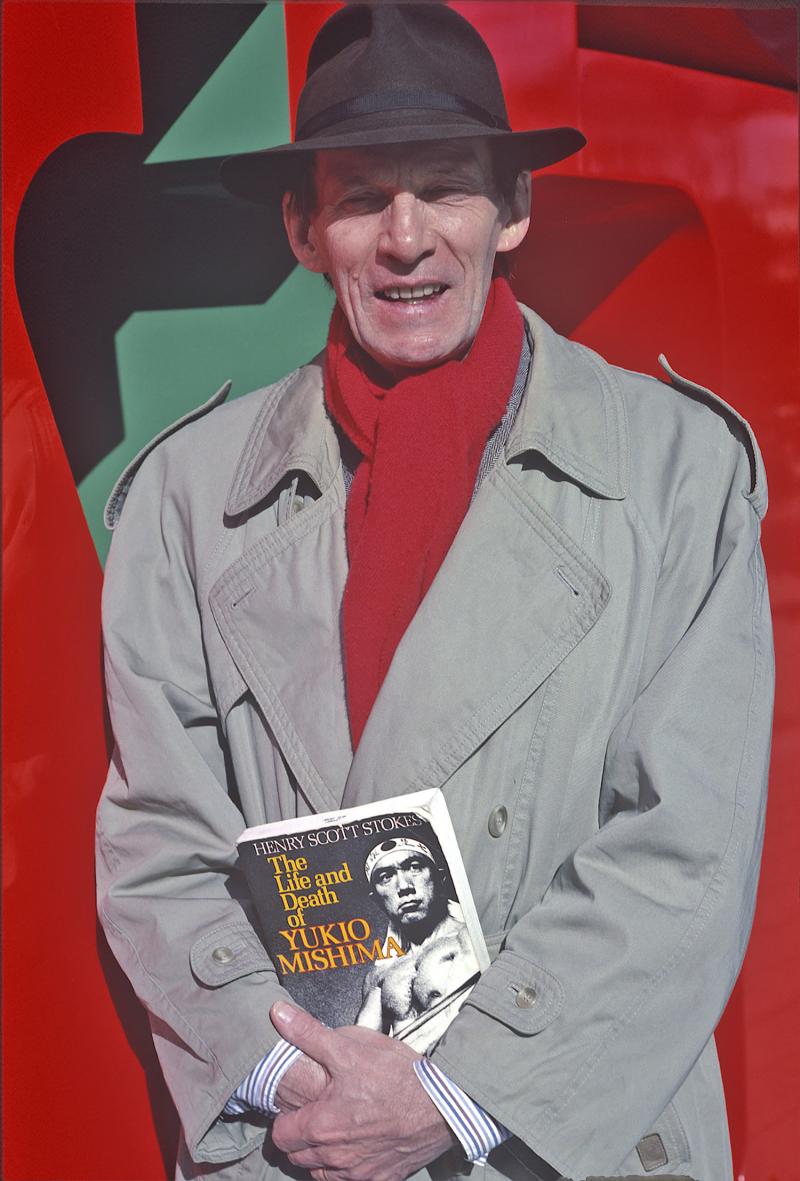

Instrumental in introducing the Japanese writer Yukio Mishima to overseas readers, the British journalist Henry Scott Stokes, would be one of the people best suited to oversee the reported facts of Mishima’s life, and, as fate would have it, his death. Scott Stokes, the author of the 1974 biography The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima, would have the triple distinction of being the sole foreign reporter at the press conference held 15 minutes after Mishima’s suicide at the Self-Defense Forces headquarters in Tokyo’s Ichigaya district, the only non-Japanese at the writer’s home the following day, and the only foreigner to attend his funeral.

What to make of a figure variously portrayed as narcissist, rightwing imperialist, keen observer of human nature, and one of the leading writers of his day, a man who staged what must rank as the most dramatic death spectacle of any Japanese in living memory? At the very least, Mishima’s life and execrable death are a compelling story, a piece of high drama that almost upstages his own fiction.

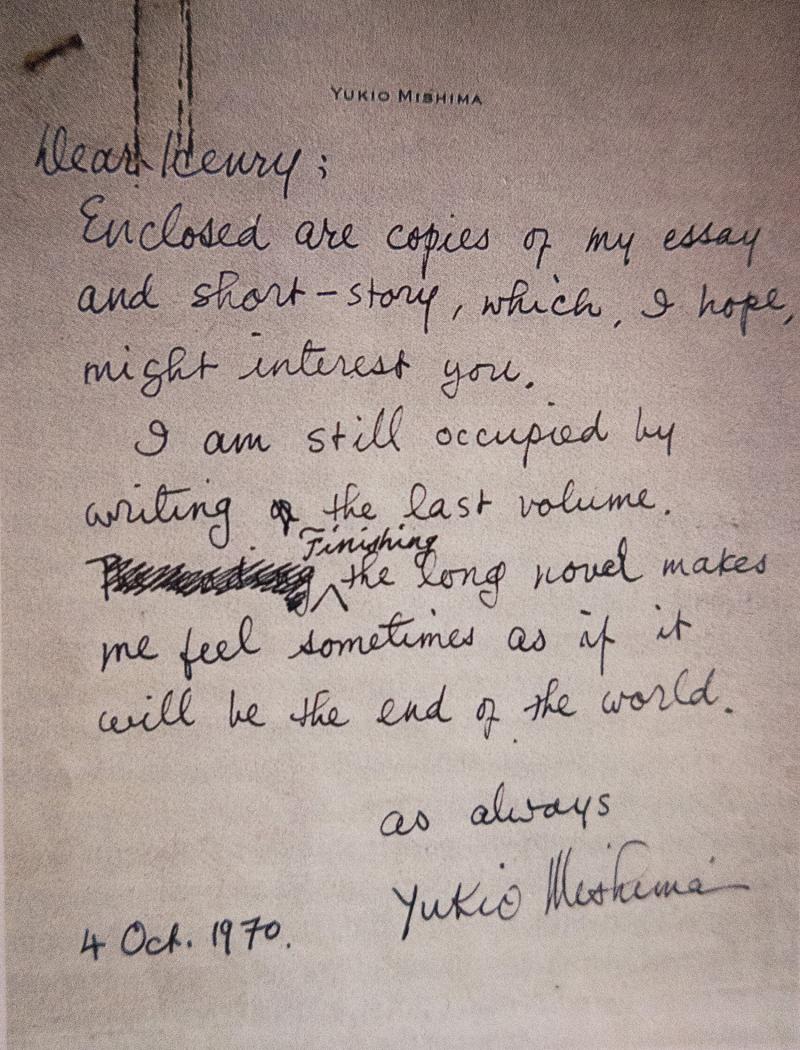

Part of that theatricality included a large exhibition of his life and work in Ikebukuro, Tokyo. Organized by Mishima himself, visitors to each of the galleries were directed through black curtains, similar to maku – the hanging textiles used in Japanese funerals to delineate boundaries. The centerpiece, and impossible to ignore, was the sword that Mishima’s companion in death, Waseda University student Masakatsu Morita, would use to decapitate the writer the following month. No one appears to have guessed at the symbolism of the event, or its function as a dress rehearsal for Mishima’s final act. Even Scott Stokes, who had received a letter from the author written on the October 4, 1970 – a month before his death – failed to recognize any hints or signals embedded in the event. That was despite the letter’s most prophetic line, which read: “Finishing the long novel (The Decay of the Angel) makes me feel sometimes as if it will be the end of the world.”

As a novelist, playwright, and essayist, Mishima was aware of the limits of even his prolific output, something that may have tempted him back to the once complimentary traditions in Japan of literature and the martial arts. In Mishima the two disciplines would combine, achieve critical mass, and then self-destruct.

November 25 marks the anniversary of Mishima’s 1970 suicide. It was no ordinary death. Mishima and members of his private army, known as the Tatenokai (Shield Society), had entered the Ichigaya office of General Mashita, and in a scene thoroughly documented by the media, the writer made a speech from the balcony appealing for the restoration of the emperor. Having failed to win over the troops assembled for his speech, much of which was inaudible above the din and commotion below, the author returned to the room, and, in the tradition of the samurai warrior, committed seppuku ritual disembowelment. Mishima’s hungry ghost has never really been laid to rest, the sepulchral image of his death never quite brushed under the blood-stained carpet of the general’s office.

A few years ago, I attended an exhibition, entitled Yukio Mishima, Dramatic History at the Kanagawa Museum of Modern Literature in Yokohama. The displays, laid out on white backgrounds beneath glass cabinets like shards of Jumon period pottery, were predictable enough: manuscripts, family photos, childhood drawings and scribblings, a postcard from Europe, envelopes and letters from one of his translators, Donald Keene, foreign editions of his work, and lurid posters reminding us of Mishima’s periodic film appearances. Not one to shy from cameras, Mishima was happy to pose for the lens whenever the occasion arose, believing perhaps, that if enough moments in time could be frozen, they might ensure his immortality. Among the family, publisher and news images were carefully staged shots, among them the famous reenactment of Saint Sebastian’s martyrdom, Mishima in loincloth, hands bound, an oiled chest bristling with arrows. Some of the most remarkable prints are from Hosoe Eikoh’s photographic homage Barakei: Ordeal by Roses.

Mishima’s physique had grown powerful in these later images, the author having subjected himself to a punishing schedule at the gym, one that would turn his stringy arms and concave chest into iron-clad plating. In this transformation, there was no doubt something of the samurai notion that one should always be ready for death, and that the warrior should not only be mentally prepared, but physically presentable.

Mishima’s life of dramatic gestures was made for cinema. The writer was no stranger to film, having written, acted in and directed a work called Patriotism, taken from his short story of the same name. It was no surprise the film premiered in Paris. In his essay, Mishima Yukio the Suicidal Dandy, Ian Buruma wrote: “Much of his grandstanding was aimed at Westerners, especially when it looked most ‘Japanese.’”

Many of Mishima’s biographers concur that his last moments were the climax of an act of intentionally lethal masochistic eroticism. There is nothing unique, of course, in the linking of sex and death, but in Mishima’s case the symbiosis of surging and exterminating forces were raised to abnormal levels. Mishima may have achieved his aims in life and literature, but the Japanese public has never quite forgiven him for the feast of death he arranged at Ichigaya, a fact that partly explains the distaste many Japanese feel – the stiffening one often senses – at the mere mention of his name.

Mishima joins other writers discredited for their extremist political leanings, including Ezra Pound, whose work has nonetheless shown considerable durability, although there will always be detractors. John Nathan, a onetime translator of Mishima, viewed him primarily as a subject, one that he could disengage from, if and when the occasion arose. This in fact is what happened when Nathan turned down an offer to translate a new novel by Mishima that failed to interest him. The writer terminated all contact with Nathan, who, returning to New York, wrote an article for Life magazine that drew an analogy between reading a Mishima work and “attending an exhibition of the world’s most ornate picture frames”.

Mishima, a militarist in the imperialist mode, stood for everything that Japan was trying to forget. Afflicted by the craving to be a tragic hero. Now the emperor had declared himself a mere mortal, Mishima would take it upon himself to be superhuman.

Instead, he ended up an acute embarrassment to the Japanese people, who were engaged in a different kind of heroic endeavor: trying to transform a discredited nation into an industrial giant and pacifist model. While most Japanese viewed the postwar period as an opportunity for moral cleansing and regeneration, the writer saw only torpor and decay, a poisoning of the very groundwater that had nourished the national spirit. He believed, perhaps, that only an act of calculated violence, a dreadful rupture, could forestall the corruption and divert the river of inaction.

It may already have been too late, however. Mishima, whose punishing training schedules had driven his body to the desired physical peak, had no intention of growing old gracefully. His ritual disembowelment, besides all its nationalist undercurrents, was the destruction of Narcissus, the sword crashing into the mirror of beauty before it could transmit back an image of decay. As the circle of people who knew the writer shrinks, the mist and grime of time impedes us from glancing clearly into the surface of that mirror.

Stephen Mansfield is a Japan-based writer and photographer, whose work has appeared in more than 60 magazines, newspapers and journals worldwide. He is the author of 20 books.