Issue:

February 2025

The following is an extract from North Korea’s Nuclear Cinema: Simulation and Neoliberal Politics in the Two Koreas by Elizabeth Shim (Bloomsbury, November 14, 2024)

North Korea’s Cold War Origins

At 1 p.m. on Oct. 14, 1945, the young man stepped out before a crowd assembled at Kirimri Stadium in Pyongyang. Kim Il Sung, a former trainee of the Soviet Red Army, had been hailed as the outstanding guerrilla leader, Captain Jin Richeng, by the Russians at the mass rally, held to honor the new Soviet occupiers and their role in the Japanese surrender on the Korean Peninsula. Dressed in a suit and tie, with a Soviet medal pinned to his lapel, Kim delivered a soaring speech about the long “Korean struggle against Japanese imperialism” as he paid tribute to “revolutionary fighters” and Korean compatriots. He also warned of internal enemies: the Korean “reactionaries” who allegedly collaborated with the Japanese during the colonial era, while calling for the foundation of a democratic people’s republic on the peninsula.

All was not well, however. Kim was plagued by rumors circulating in Korea at the time that claimed he was a “fake” revolutionary posing as a legendary general. By the end of World War II, the name Kim Il Sung was associated with several guerrilla leaders older than the 33-year-old man the Soviets endorsed as their appointee on the peninsula. Russian propaganda that blurred the line between fiction and reality had backfired after it promoted the idea that their Kim Il Sung was the only guerrilla hero, and that all Kim Il Sung lore could be attributed to one man.

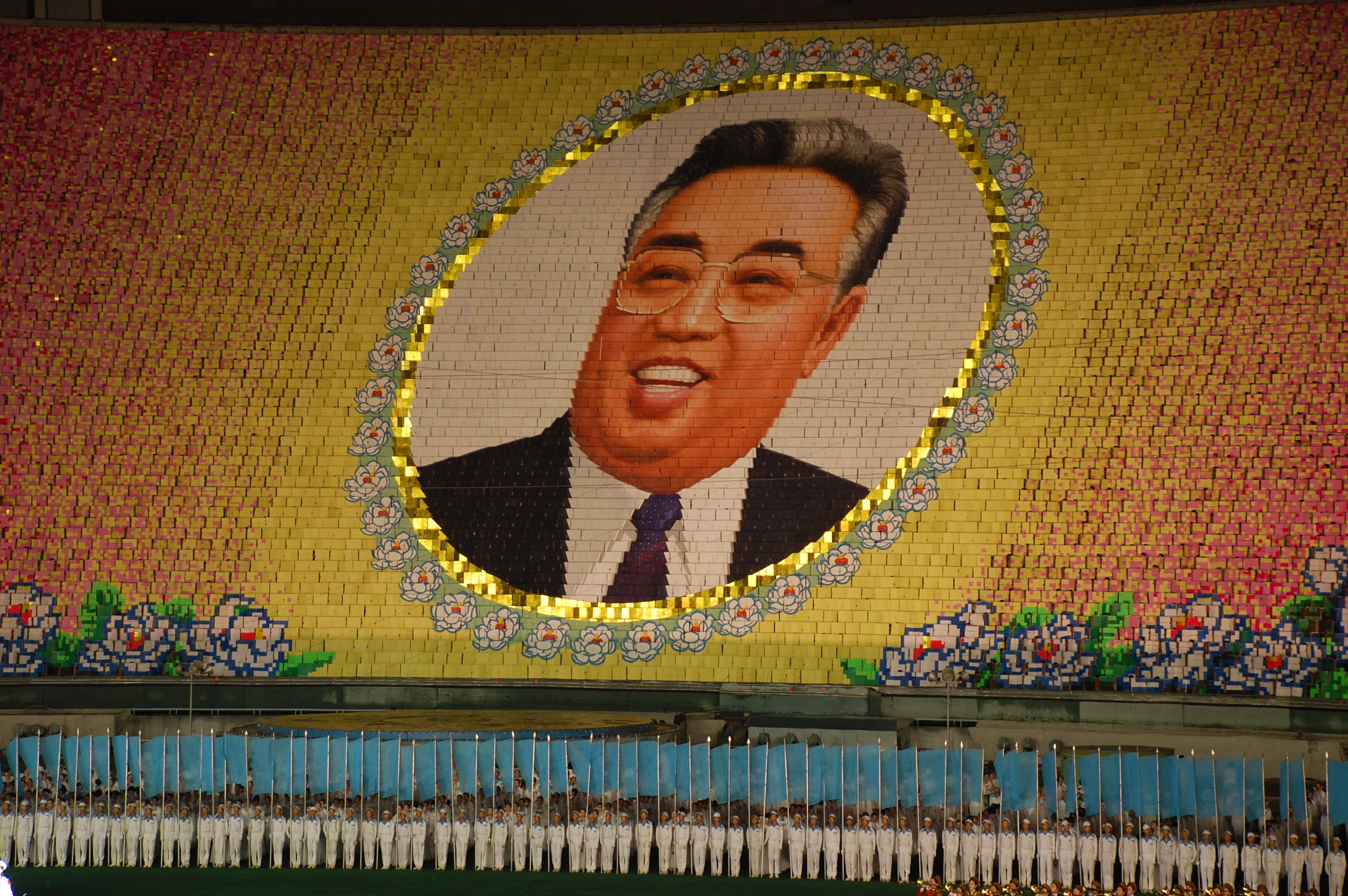

North Korea’s founding history, we have accepted, began with the arrival of the non-fictional figure of Kim on the peninsula. Kim did arrive with the Soviets, but he never engaged in the actual combat that ended Japanese rule in 1945. He instead arrived in Soviet-occupied Korea by boat, at the port of Wonsan, ready to deliver speeches under the watchful eyes of his Russian sponsors and pose for photos with the local population. Kim’s performance of a Korean “hero” who had returned home fictionalized his own body, his very existence, erasing the possibility he was yet another foreign occupation, this time disguised in a Korean identity. In later years, Kim’s suit-and-tie figure at the 1945 rally would appear in retouched photos showing him without his Soviet medal or the row of Russian generals who once stood behind him at Kirimri Stadium. As Kim’s fictional self took root everywhere, he also disappeared into the existing world and everyday life. The real Kim, as subject, vanished under the cumulative effects of Soviet and later North Korean propaganda that suppressed the rumors of his “fake” credentials. The future leader would then emerge as an object of the purest form: “Father” and “Eternal Leader” of the Korean people - a propaganda effect replicated across North Korea and its future project of nuclear cinema and spectacle. He would also be called the “Eternal Sun” – the light of the people, who, without his presence, were indoctrinated to believe he was the giver of life, their infinite savior.

This book in part tells a story of the unsung role of technologies of seeing, in capturing the invisible and unspoken realms of North Korea and the nuclear weapon state. The regime’s propaganda across generations have shaped its modernity, postmodernity, perception and politics. From Kim Il Sung to Kim Jong Un, state reality has been coated by a veneer of fiction that has gone unchallenged. North Korea, its very existence, supports a principle of propaganda: Repeat a lie often enough and it becomes truth. Yet, it is elements of the fictional that have become the ruling facts of our present day. Lies, by definition, are detached from any real material objects or historical events, yet the world at large remains deeply concerned, at times terrified, of North Korea’s capabilities – a subject of heavy speculation.

A study of North Korea’s media alongside the historical record can teach us hidden truths about the secretive regime. This work not only explores that nether space of the “optical unconscious,” (Benjamin, 1979) but also claims that it is modern and contemporary media -- newspaper articles, doctored photographs, documentaries and film, that have engineered the appearance, disappearance then reemergence of the regime’s key figures and its symbolic signifiers.

North Korea is the story of a twentieth century propaganda state that has in some ways safely crossed the bridge into the post-Cold War space of the 21st century. But the 21st century has presented challenges for the regime: the covert introduction of capitalist media to large segments of the population via new technologies that have weakened the boundaries of the state. Against this backdrop, North Korea’s policy of nuclear weapons development emerged as simulated deterrence in the digital video space, restoring North Korea’s “reality” on networks like CNN and the BBC by providing injections of the physical world to keep the illusion alive.

This book argues South Korea’s digital media advances and other forms of “global flow” factored significantly into North Korea’s decision to demonstrate nuclear power, as the South’s media deterritorialized the political space of North Korea and introduced capitalist material culture. Weapons display, its availability on replicable video footage, can be evaluated as a form of cultural expenditure. Nuclear weapons and their ancillary facilities steered domestic attention to the importance of the state and centralized power at a time when increased marketization and North Korean exposure to South Korean media has generated change, spurred migration and movement.

While digital spaces have extended the life of the video-mediated nuclear weapon state and international media coverage helped reinvent the country, the threat of a catastrophic nuclear conflict poses a clear and present danger on the Korean Peninsula and the region. This book shows how North Korea has prioritized convincing other states and its own population to believe in its desired image, often times over engaging in actual armed conflict. Yet the risk remains that the excesses of a video-mediated nuclear North Korea could enact a total annihilation of human lives - a power that has been developed and harbored across three generations of rulers. The solution is for stakeholders in the region and beyond to acquire new ways of seeing and verifying – and perhaps more importantly understanding the hidden forces that have operated in North and South within the context of their modernization.

Elizabeth Shim was a CSIS Korea Chair Nextgen Scholar, is currently Senior Principal of Haven Tower Group and previously United Press International’s Chief Asia Writer. She has written for the Associated Press, the National Interest, and the South China Morning Post, and is co-author of Korean War in Color (2011), and a chapter contributor to Media Technologies for Work and Play in East Asia (2021).