Issue:

March 2025

Organizers are hoping to banish negative coverage of the World Expo when the event opens next month

In the sweltering Japanese summer of 1985, I was among more than 20 million visitors to the Tsukuba Exposition, where tremendous lines formed outside 48 national pavilions set up under the theme Dwellings and Surroundings - Science and Technology for Man at Home. Nursing sunburn so bad even dermatologists would have struggled to classify it, I found shelter at the national pavilions of the USSR and Namibia.

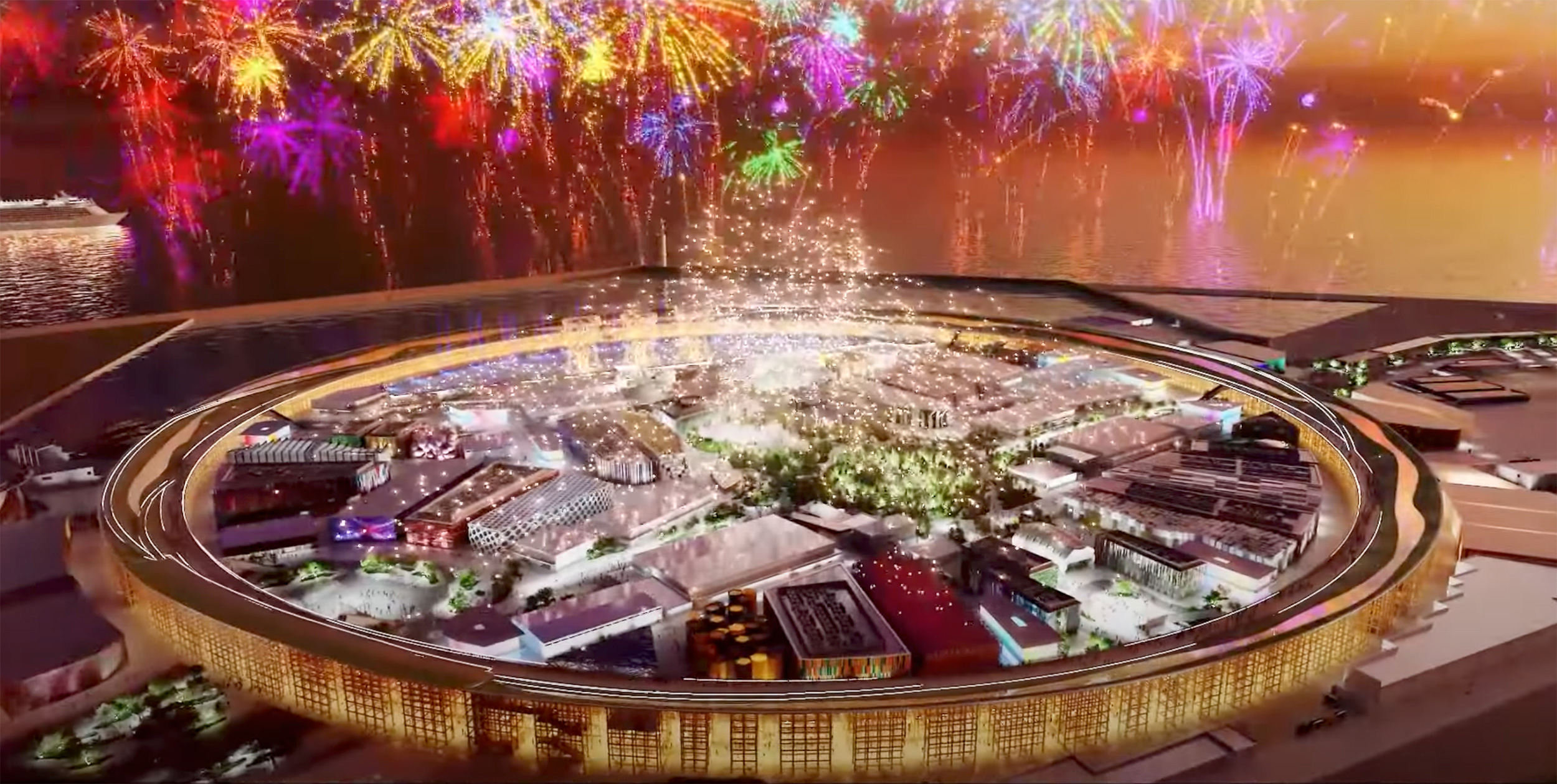

Fast-forward 40 years, and Japan is preparing to host another Expo, this time on Osaka’s artificial Yumenoshima island. Ahead of the event, which opens next month, I looked into the 19th century origins of World Expositions to see if they were still of any relevance in a contemporary world dominated by technology.

The first Expo opened in London in 1851, organized by Prince Albert, with Schweppes as sponsor and Thomas Cook as official travel agent. The World’s Fair, as it was known, offered Victorian pomp and circumstance as well as nascent technology, and drew over six million visitors. The Crystal Palace – an architectural wonder in its own right – hosted British colonies and dependencies, along with 44 exhibitor nations, and turned a profit through tiered pricing, special guests, and souvenir sales.

In 1970, when Japan held its first Expo, in Osaka, 64 million people marveled at Taro Yamamoto’s 70-meter-tall Tower of the Sun. Most attendees had never been abroad, but Osaka’s window on the world, along with a display of recently retrieved moon rocks, offered them a passport into new places. The sense of change and opportunity that ran through the Showa Era was on conspicuous display. But like the Tokyo Olympics six years earlier, Japan would struggle to recapture the excitement of its inaugural Expo.

Osaka 1970 featured electric cars, the ethernet, a human washing machine, IMAX, the first conveyor belt sushi, and only six days of 35C-plus temperatures. That compares with 41 days of extreme heat in the city recorded last year, although the weather will count for little this year for visitors taking a seat at Kurasushi’s 135-meter indoor counter.

Fifteen years after the first Osaka event, it was Tsukuba’s turn, followed by Aichi in 2005, which drew 22 million people - me included – exceeding its visitor targets. This time, Osaka’s organizers expect 28.2 million visitors during its six-month run.

Ticket sales so far have barely reached half the target total, however, with corporate buyers responsible for 82% of sales. With Expo expenditures ballooning to more than ¥235 billion – 90% higher than the initial estimate – national and local organizers hope Japan’s 2024 record inflow of nearly 37 million tourists will bring at least 3.5 million people to Osaka.

Japanese people themselves seem underwhelmed. A Mainichi Shimbun survey in mid-January found that only 16% of respondents planned to visit, with 67% adamant they would stay away.

Price may be a factor. Tickets range from ¥1,800 to ¥4,200 for children, and up to ¥7,500 for adults, although visitors earn discounts by jointly purchasing Universal Studio Japan tickets or multi-day options. At the request of the prime minister, Shigeru Ishiba, organizers introduced same-day sales to spark demand – a move that could boost numbers but also lead to longer lines.

The media have not been particularly upbeat. The Asahi Shimbun described the Expo theme, Designing Future Society for Our Lives, as vague, while a Yomiuri Shimbun editorial in mid-February was even more direct. When users visit the official website, it said, “they only find it is filled with explanations of abstract ideals, and not many countries describe the details of their exhibits”.

The Japan Association for the 2025 World Exposition, the editorial continued, “has said that it cannot pinpoint the highlights of the Expo, given that values are becoming increasingly diverse. But then what should visitors look forward to?”

To be fair, there is plenty to look forward to, not least Sou Fujimoto’s wooden Grand Ring, which, like all other Expo structures, will be dismantled so that the site can be prepared to host Japan’s first integrated casino complex.

Some lawmakers have decried the ¥34.4 billion Grand Ring as the “most expensive parasol in the world”, although I doubt Expo visitors arriving in the summer will be complaining.

Other highlights include a 17-meter Gundam, a hydrogen-fueled ferry, 70 food stalls, a Martian meteorite, a heart made from induced pluripotent stem cells, and 47 country pavilions that include, on Japan’s 13,000-meter site, a Hello Kitty x Algae mashup. The mind boggles.

The beloved character has made PR appearances alongside the official Expo mascot Myaku-Myaku, dubbed by the Nikkei business newspaper as “creepy but cute”.

Foreign VIPs will be among the visitors, including, perhaps, Donald Trump making an appearance at the U.S pavilion in July. Ishiba, whose Washington summit in February failed to give him much of a boost in his domestic approval ratings, could gamble on another photo op with the U.S. president to give him a fillip ahead of what promise to be difficult upper house elections this summer.

J-Pop artist Ado will open the Expo, the 22-year-old anonymous artist appearing as his trademark avatar and only in silhouette. Regardless, 10,000 fans are expected to go along for the opening.

Another unlikely highlight will be the public restrooms using stones once intended for Osaka Castle. Needless to say, the facilities will need to live up to their enormous price tag, in some cases as high as ¥200 million.

The Expo minister and other officials insisted – not particularly convincingly - that the cost was fairly typical of public restrooms and by no means a case of flushing cash down the toilet.

Once the Expo closes its doors in October, work will begin to convert the site into a ¥1.1 trillion casino-centered Integrated Resort due to open in 2030. In one sense, Osaka’s second bite of the Expo apple is just the warm-up act for a more permanent transformation of Yumenoshima. Whether or not it lives up to its “dream island” name remains to be seen.

Dan Sloan is president of the FCCJ. He joined the club in 1994 and previously served as President in 2004 and 2005-06. He reported for Knight-Ridder and Reuters for nearly two decades.