Issue:

How a highly respected newspaper ended up in the crosshairs of rabid rivals, righteous revisionists and a terribly talkative Texan.

Before this year it is doubtful that many Japanese knew the location of Glendale, Calif. an L.A. suburb with a population of 200,000 known for animation production, a large Asian population and the Big Boy fast food chain. That has changed, thanks to an unimposing bronze statue of a young woman installed last year in a local park that has become a microcosm of the toxic history war between Japan and South Korea.

The statue was meant to commemorate the suffering of women herded into wartime Japanese brothels and to symbolize justice denied. Since the unveiling, however, the city has been targeted by Japanese diplomatic protests, hundreds of angry letters and a lawsuit demanding its removal.

The dispute took a farcical turn on Oct. 21, when the city council heard testimony from long winded rightist video blogger Tony Marano. Marano travelled hundreds of miles from his home, presumably on his own dime, and took time off from warning against nefarious communists, Koreans who “eat dogs off the street” and President Obama’s plan to turn America into a Muslim nation, to pick up the cudgel against the hated memorial.

Known among nationalist circles here as the “Texas Oyaji,” Marano appeared to believe he was speaking on behalf of an entire country as he told the council that the statue “has been perceived by Japan and by the people of Japan as an insult and a sleight to their honor.” He urged the council to demonstrate that the city was not “bashing” Japan.

How did it come to this a nondescript community on the edge of Los Angeles’ massive urban sprawl becoming the focus of a struggle between two East Asian nations for the world’s sympathy, if not its conscience?

Apparently, if rightist revisionists are to be believed, the Asahi Shimbun is to blame for this, as well as for the entire globally accepted history of the Japanese military’s involvement in forcing women into sexual slavery during World War II.

It began when Japan’s second most read newspaper ran a series of articles in the 1990s on comfort women, with one of its sources a man named Seiji Yoshida. In the revisionist narrative, that triggered the 1993 Kono Statement that acknowledged the army’s role and eventually led to the U.S. House Resolution 121 of 2007, calling on Japan’s government to “formally acknowledge and apologize in a clear and unequivocal manner” for the sordid episode.

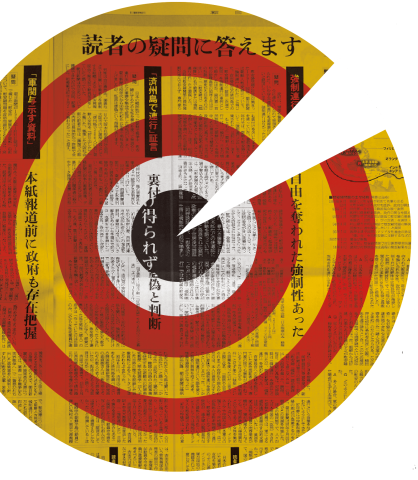

So when the Asahi belatedly apologized for the series in August, admitting that Yoshida was discredited, it opened the door to a parade of chest thumping revisionists. [See “The Asahi’s Costly Admission,” Number 1 Shimbun, Sept. 2014].

The criticism of the paper began at the top. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe repeatedly hauled the newspaper over the coals for its coverage. “Many people were hurt, saddened and angered by the Asahi’s false reports,” that “damaged our honor around the world,” he said.

The Sankei and the Yomiuri showed no mercy in their attacks. Even the Japan News, the Englishlanguage edition of the Yomiuri, ran close to 50 articles, editorials and guest columns in late summer and fall on the rival paper’s woes, including a four part series in which it claimed that “the Asahi’s stories on the comfort women issue over the decades have been a significant factor in the entrenchment of the distorted view that ‘the Japanese military systematically and forcibly took away women to serve as comfort women’ for its soldiers.”

TWISTED FACTS, TWISTED WORDS

In fact, the Kono Statement was the product of years of campaigning by Korean and other former military sex slaves. Likewise, the discredited Yoshida memoir and Asahi’s reporting of it had nothing to do with Resolution 121 so said the group of experts who helped write it. The scholars were moved to make this clear after the Mainichi newspaper reported exactly the opposite after interviewing them. “All of us were astonished,” they recall.

“We had unequivocally told the reporters that the Yoshida memoir and Asahi’s reporting of it were not factors in the consideration, drafting, or defense of the [resolution],” they said in a statement. “We emphasized that one discredited source would not form the basis of research for Congress.” In fact, they said, “There was ample documentary and testimonial evidence from across the Indo Pacific region to support the fact that Imperial Japan organized and managed a system of sexual slavery for its military as well as for its colonial officials, businessmen and overseas workers.”

The odd sense shared by the Resolution 121 experts that the Mainichi reporters had made their minds up before they walked through the door, is one we recognize. After the Asahi’s retraction, we were approached by several Japanese news organizations asking the same question: Wasn’t the Asahi coverage of the comfort issue a major influence on reporting by foreign correspondents?

We both have a clear answer: no. Neither of us had even heard of Yoshida until this year. Over the last decade, however, we have interviewed many of these women first hand, in South Korea and elsewhere. We have visited the House of Sharing, a museum and communal refuge for surviving comfort women outside of Seoul.

The eight residents include Kang Il-chul, who still bears the physical scars of the two years she spent working in a Japanese military brothel in occupied northwest China, thousands of miles from her home in the southern half of the Korean peninsula. “I was put in a tiny room and made to sleep with about 10 to 20 soldiers a day,” Kang said.

When confronted with claims that no evidence exists that she and her contemporaries were coerced, she leaned forward to reveal the wounds on her scalp the result, she said, of frequent beatings by the military police.

Kang, who married a Chinese man after the war, did not return to South Korea until 2000. “To hear Japan’s leaders accuse us of being liars makes me sad and angry,” the 87 year old said in 2012.

An unofficial campaign of intimidation has been launched against ex Asahi journalists. This campaign has precedent: ultra rightists targeting “anti Japanese elements” in the media murdered Asahi journalist Tomohiro Kojiri in 1987. The main target this time is Takashi Uemura, a former Seoul bureau chief now vilified for his comfort women coverage.

An article in the weekly magazine Shukan Bunshun, expressing disbelief that he was to be employed at Kobe Shoin Women’s University, triggered a tsunami of hate mail. “As soon as the story came out, 200 messages a week flooded into the university office,” Uemura said.

He negotiated a settlement with the school, then retreated to his native Sapporo, where he found part time work at Hokusei Gakuen University. The hate trail followed him, this time including a threat to blow up the university. As the No.1 Shimbun goes go to press a suspect is in police custody for making that threat, and Uemura has managed to hang on to his job.

A national “anti- Asahi Shimbun” committee discussed plans at its inaugural conference to widen the boycott

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

Where might all this be heading? A national “anti Asahi Shimbun” committee, led by lawmaker Nariaki Nakayama, discussed plans at its inaugural conference to widen the boy cott and haul Asahi editors and journalists before the Diet. The Texas Oyaji stepped forward with a claim that the Asahi dishonored many members of the former Japanese Imperial army by labeling them as “sex offenders.”

Yoshiko Sakurai, a high profile revisionist, added an ominous note. “I believe the people at the Asahi perhaps fail to comprehend what a real national crisis their decades of shoddy reporting has brought about,” she blogged. “In all candor, I am tempted to say that there really is no medicine that can cure the Asahi.”

And just when it seemed that the Yomiuri might have tired of pounding its rival, it published a 24 page online pamphlet titled “Myth and Truth in East Asia” in late October that again took the Asahi to task. And the Sankei publishing group announced that it wasn’t ready to retreat from the attack with an entire issue of the magazine Seiron devoted to more Asahi bashing.

All this, along with a boycott campaign led by the Sankei, has taken its toll. The Asahi’s circulation is down by 770,000 since November 2013.

It is unreasonable to expect newspapers to resist the temptation to crow about errors made by a rival publication. The same would almost certainly happen in the UK, even among respectable broadsheets. But in their sustained criticism, the Sankei and Yomiuri appear to be doing the bidding of the revisionist movement.

Revisionists, however, deny they are trying to crush the paper. “I hope we can force the Asahi to change its stripes and admit its past mistakes,” says Tony Kase, collaborator with Henry Scott Stokes on the recent revisionist bestseller False hoods of the Allied Nations’ Victorious View of History, as Seen by a British Journalist. He says he has “many dear friends” at the Asahi. “It did many good things, including supporting our last war in liberating the rest of Asia.”

In the spectrum of difficult choices facing Japan’s liberal flagship, reverting to its flag waving, wartime incarnation might seem the least palatable. Whatever its editors decide, however, the nationalist knives are out.

In fact, there are signs that criticism of the Asahi is transforming into a sustained campaign to discredit the Kono statement, as the region prepares to mark the 70th anniversary of the end of WWII next summer.

In October, Abe was quoted saying that, “baseless, slanderous claims that the entire nation regarded [women] as sexual slaves are being made all over the world.” And his administration has demanded changes to a 1996 report by the UN commission on human rights known as the Coomaras wamy Report.

“Japan thinks that, by damaging the credibility of the Coomaraswamy Report, it can change the perception in the international community that the comfort women were sex slaves,” Han Hye-in, researcher at the Academy of East Asian Studies at Sungkyunkwan University, told the South Korean Hankyoreh newspaper.

In response, perhaps the last word should go to Yu Hui-nam, a House of Sharing resident who was 16 when she was taken to work in a brothel in Osaka. “I was ashamed and humiliated,” she said of her initial refusal to return to South Korea after Japan’s defeat. She revealed the truth about her past only when other former comfort women started coming forward many years later.

“We were snatched, like flowers that have been picked before they bloom.”

David McNeill writes for the Independent, the Irish Times, the Economist and other publications and is a coordinator of the electronic journal www.japanfocus.org. Justin McCurry is the Japan and Korea correspondent for the Guardian and Observer newspapers in London. He contributes to the Christian Science Monitor and the Lancet medical journal, and makes regular appearances on France 24 TV.