Issue:

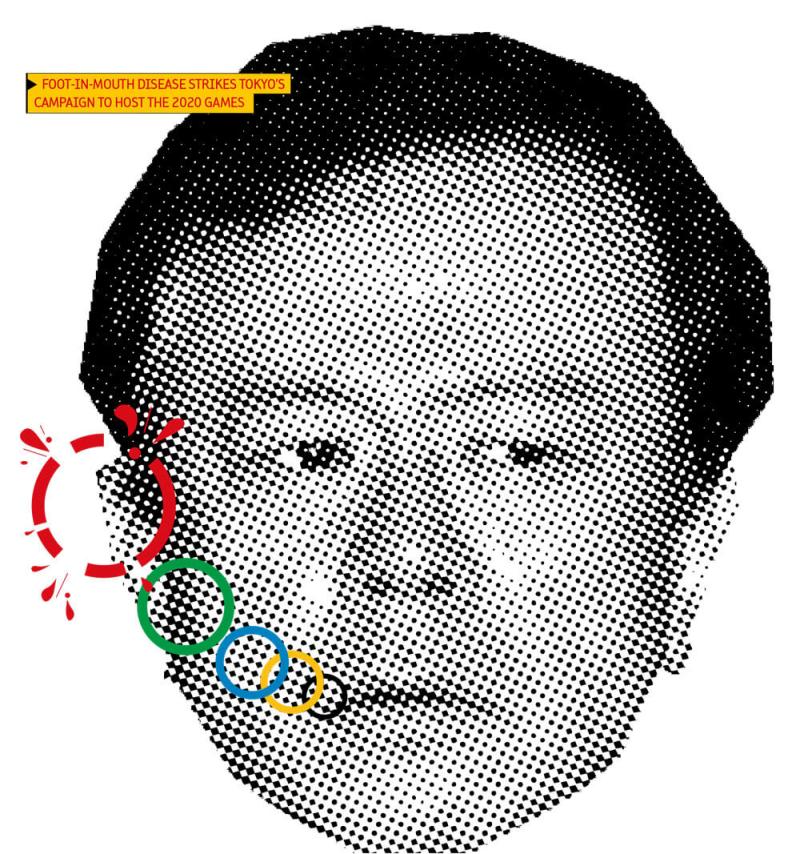

If Tokyo fails in its second consecutive attempt to become host city of the Summer Olympics, the blame game would have no lack of potential targets. The furor surrounding recent comments on wartime sex slaves by the mayor of Osaka, Toru Hashimoto, and the perception that diplomatic expediency, not conviction, led the prime minister, Shinzo Abe, to honor official apologies for Japan's wartime conduct have hardly helped the country's standing overseas, particularly in Asia. But there is no more worthy a target than the man who occupies the office of the capital’s governor, Naoki Inose.

In an interview with the New York Times in April, Inose displayed breathtaking ignorance of Turkey, and of IOC rules banning bidding cities from commenting on bids by rival candidates.

Displaying the same gift for diplomacy as Shintaro Ishihara, the man he replaced as governor, Inose said of Istanbul’s bid: “So, from time to time, like Brazil, I think it’s good to have a venue for the first time. But Islamic countries, the only thing they share in common is Allah and they are fighting with each other, and they have classes.”

Having stomped over Turkish religious and cultural sensibilities, Inose also sailed close to the IOC wind by highlighting perceived weaknesses in Istanbul’s vision for the Games. “I don’t mean to flatter, but London is in a developed country whose sense of hospitality is excellent,” he said. “Tokyo’s is also excellent. But other cities, not so much.”

He went on: “For the athletes, where will be the best place to be? Well, compare the two countries where they have yet to build infrastructure [or] very sophisticated facilities.”

The remarks drew an angry response from Turkey. The country’s youth and sports minister, Suat Kiliç, took to Twitter to denounce them as “unfair and saddening,” and a clear violation of the Olympic spirit.

Spying an opportunity to capitalize on Inose’s intemperance, Kilic pointed out that Istanbul officials “haven’t made any impairing comments about any other candidate city until now, and we won’t.”

‘TOKYO MAY HAVE ESCAPED OFFICIAL CENSURE, BUT THAT DOES NOT MEAN THE INOSE STORM HAS BLOWN ITSELF OUT.’

Turkey’s prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, even suggested only half jokingly that Shinzo Abe withdraw Tokyo’s bid. Abe, who was in Turkey in May to secure a US$22 billion deal to build a nuclear facility there, politely declined, but said he would be the “first to applaud” Istanbul if it is named host city on its fifth attempt.

One wonders who was briefing Inose in the messy aftermath of publication of the New York Times article. Initially, the governor resorted to the time honored tactic of blaming the messenger, accusing the newspaper of taking his comments out of context. He appeared to have forgotten that the interview had been conducted by Hiroko Tabuchi, a Japanese journalist, and Ken Belson, an American reporter who speaks Japanese, in the presence of an interpreter upon whose translation the article was based.

In response, the New York Times said in a statement that it was “completely confident in the reporting for our article.”

When Inose’s apology finally arrived, it came with a large helping of hubris. “I regrettably acknowledge, however, that some of my words might be considered inappropriate and consequently would like to offer my sincere apology,” he said. “I want to keep campaigning strictly in accordance with the IOC rules that one should not criticise other cities.”

Yet again, though, what little media nous Inose had acquired since becoming governor quickly evaporated. Inose claimed that the New York Times interview had focused on “a small number of comments” and did not reflect his “sincere and wider thoughts” about the bidding contest. Then, in an inexplicable show of conceit, he went on Twitter to say that the debacle had at least taught him “who are my enemies and who are my allies.”

Inose, it must be said, had inherited a tricky Olympic brief from Ishihara, whose attempt last spring to buy the Senkakus set off a bitter territorial row that continues today. Ishihara’s long record of provoking China will not have gone unnoticed by IOC delegates, and it is not unreasonable to believe that Chinese members of the committee will use their influence on African and Asian colleagues to try to scupper Tokyo’s bid. Inose, remember, was Ishihara’s deputy and his favoured successor.

The Yomiuri Shimbun speculated that Inose’s record breaking election victory late last year had gone to his head, to the detriment of Tokyo’s bid. “We are very concerned how the Tokyo governor’s remarks will affect the voting behavior of IOC members of other countries, particularly those from Islamic countries,” it said in an editorial.

It was left to Tsunekazu Takeda, the likable and no doubt exasperated president of the Japan Olympic Committee, to pick up the pieces.

“Although [Inose’s] sincere thoughts differ from the content of the story published, he acknowledges that his comments related to another bid city and religion may have conflicted with the IOC guidelines and, as a result, offered his profound apologies,” Takeda said in a statement.

The show of contrition worked: the IOC said it had noted Inose’s remarks but would not be taking action, simply reminding “all candidates of the rules pertaining to the bidding process.”

In a recent appearance at the FCCJ, Takeda went to great lengths to avoid any detailed discussion of “Inose gate.” “Inose made remarks for which he has apologized and the IOC says the case is now closed,” he said. “We’re totally focused on delivering the best possible Games. Is that clear?”

Takeda repeated Tokyo’s three pronged Olympic mantra of “delivery, celebration and innovation” that the city hopes will secure it victory when the IOC votes to decide the 2020 host in Buenos Aires on Sept. 7.

Aside from drawing on Japan’s technological prowess, advanced infrastructure and stable source of funding, Tokyo is promising a “downtown” Games in which 85 percent of the venues are located within a five mile radius of the Olympic Village.

“The city enjoys the largest GDP of any city in the world,” Takeda said. “It already has a Games fund of US$4.5 billion in the bank, as well as full government financial guarantees.”

The city can count itself fortunate that its most powerful elected representative betrayed his prejudices when he did. The consensus among Olympic bid watchers is that the final three months of the process are the most decisive. Witness how Paris, long considered the frontrunner for 2012, was pipped at the post by London; ditto Chicago and Rio de Janeiro, host of the 2016 Games.

As Tokyo, Istanbul and Madrid enter the final, frantic phase of lobbying beginning with presentations to the IOC in St. Petersburg at the end of May none can afford to be complacent.

Tokyo may have escaped official censure, but that does not mean the Inose storm has blown itself out, says Owen Gibson, chief sports correspondent for the Guardian.

“Such is the weird world of international sports diplomacy that this sort of thing can have a lasting impact,” Gibson told No.1 Shimbun.

“It was particularly unfortunate that his comments could be compared unfavorably with Istanbul’s ‘East meets West’ rhetoric. If you look at all the recent winning bids Beijing, London and Rio in different ways they have all campaigned on a message of opening themselves up to the world, hosting a global celebration. But Inose’s comments seemed to run contrary to all that.”

That said, Inose’s outburst at least demonstrated that Tokyo “really wants to win” the contest, added Gibson, who has covered two Olympic bids and interviewed the governor in London earlier this year.

There are, though, flaws that Tokyo must address between now and September. Japan has already hosted the summer Games, in 1964, when it persuaded the IOC that the event would demonstrate Japan’s emergence from the ashes of war to become an economic force and a responsible member of the international community.

While the 2020 campaign has received high marks for logistics and practical considerations, it lacks the “emotional resonance” of almost 50 years ago, says Gibson.

Yet using the Games to demonstrate Japan’s continuing recovery from the March 11, 2011 triple disaster could prove counterproductive. Every time bid officials offer justified reassurances about radiation levels in Tokyo, they remind the rest of the world that Fukushima Daiichi power plant remains vulnerable; and when Takeda describes Tokyo as “safe” as he did several times during his FCCJ appearance he invites inevitable questions about the perennial threat to Tokyo from a major earthquake.

Even so, Gibson, noting that Tokyo had hired the same agency London and Rio used to write their speeches and produce promotional literature, believes the city is “still very much in the race. There’s no doubt Istanbul’s is the more expansive, expensive vision, but if there is a sense that Istanbul is too much of a risk, then Tokyo will benefit.

“Tokyo has to sell itself more effectively between now and September and prove that the Japanese people really want to host it, something that has undermined its bids in the past.”

A question mark hangs over just how enthusiastic Tokyo residents are about the prospect of hosting the Games. “In general, people in Tokyo and the rest of Japan don’t seem that interested,” a Japanese writer for a weekly magazine who has written about Tokyo’s bid told No.1 Shimbun.

“Tokyo has hosted the Olympics before and the Nagano Winter Olympics in 1998 created a lot of debt,” the writer, who did not wish to be named, said. “Japan itself is in debt, so people don’t understand why the Olympics should be a priority. I can understand the motivation behind Madrid and Istanbul’s bids, but not Tokyo’s.”

As the three candidate cities enter the decisive stages of the bidding contest, Tokyo may come to thank Inose for his outburst. Given the events of recent weeks, Japan’s Olympic officials at least know they must find a way to keep Tokyo’s trouble somely loquacious governor in the shadows for the remainder of the campaign … before irreparable harm is done.

Justin McCurry is Japan and Korea correspondent for the Guardian and Observer newspapers in London, and Tokyo correspondent for the Christience Monitor. He also reports on Japan and South Korea for France 24 TV.