Issue:

February 2025

Japan’s feline obsession has left its paw prints all over the publishing industry

Enter almost any of the larger book stores in the world, say Barnes & Noble Union Square in New York or Waterstones in London, and chances are you will come across a cat literature section. Like the kind of displays of work that appear after a Nobel Prize for Literature winner has been announced, the exhibits are both eye-catching and, by all accounts, well-supported.

A closer look reveals that many of the titles are books by Japanese authors, the result in many cases, of efforts by enthusiastic translators, who have been instrumental in drawing attention to promising works, and to persuading publishers to bring them out. Judging from the sales figures, cats are leaving visible paw prints across the publishing industry.

I probably wouldn’t be delving into cat literature in such detail had my wife and I had not acquired a pet from a Tokyo shelter a couple of years ago. It’s been a fascinating experience, though not without its challenges. It’s fair to say that, along with the pleasures of co-existence, a rescue cat will bring an undocumented history into your home, behavioral traits, even embedded traumas, that the well-meaning volunteers who try to place animals are either not aware of or choose not to mention in their endeavor to find an animal a good home.

It seems we have lived in the company of cats for millennia. The Greeks had a few things to say about the mythic quality and beguiling mysteries of felines, but cats appear to have been first represented, not in words, but art. Cats were revered in ancient Egypt. Totemic animals, they feature on wall friezes as minor gods. Pilgrims even bought cat mummies, presenting them as votive offerings to temples. In a later age, they received less dignified treatment from their colonial masters. Of the 180,000 cat mummies shipped to England in the late 19th century, for example, only a handful found their way into museums. The rest were sold as fertilizer. The remaining specimens – I have seen a number in faintly embalming fluid-infused storerooms at the British Museum – look distinctly aggrieved.

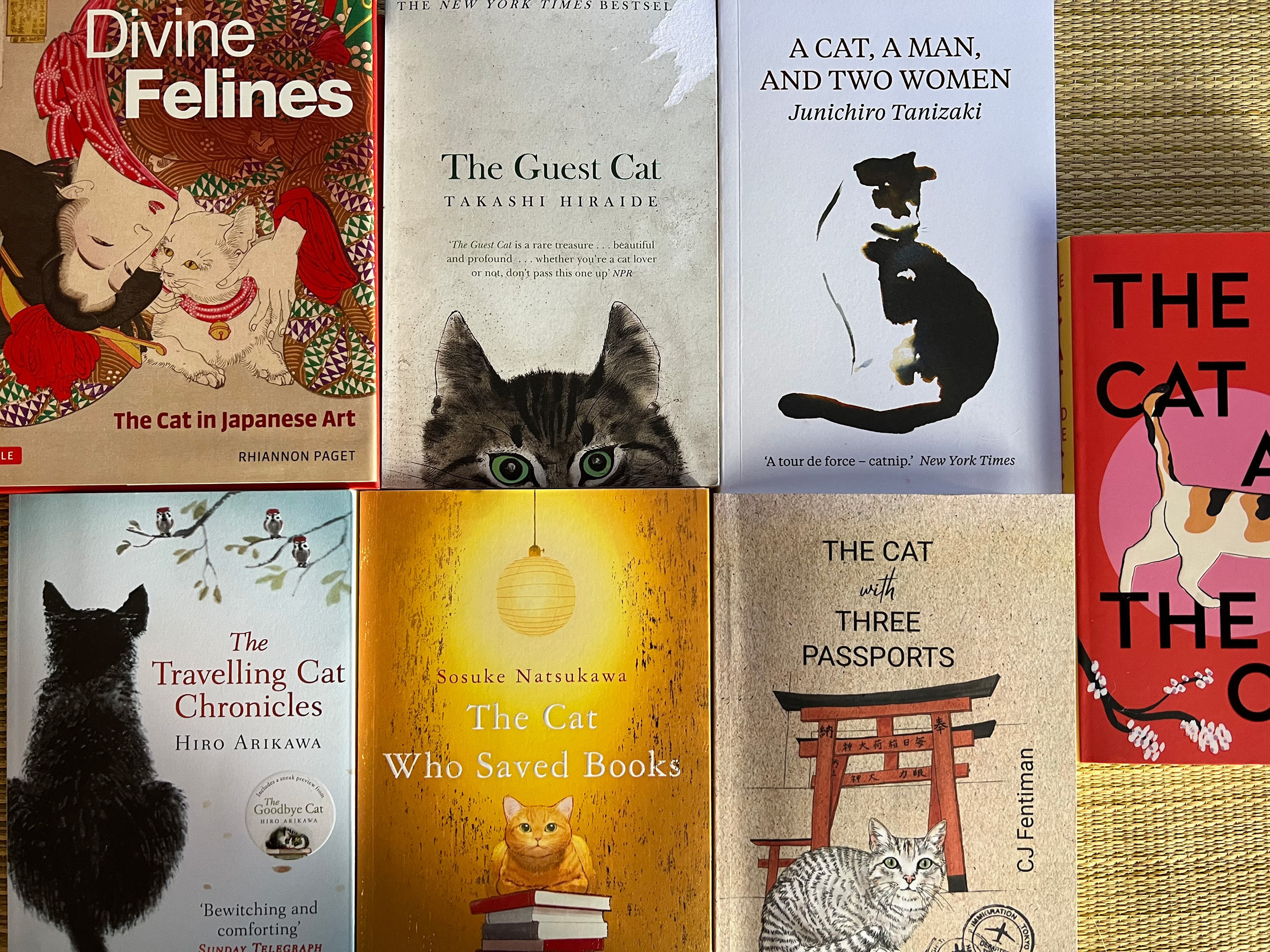

Cats are believed to have been introduced into Japan in the sixth century, along with Buddhism, with temples employing them to protect sacred texts from vermin. Cats as human companions are described with great affection in early Heian era (794-1185) literature, particularly in diaries. Quite how the current popularity of cat-related books started in Japan, though, is unclear. The sly cynicism and humor of Natsume Soseki’s feline protagonist in his satirical novel, I Am A Cat, published in 1906, was surely a milestone, but there were other literary masters who were drawn to the expressive potential of these creatures, including Junichiro Tanizaki, whose short 1950 novel A Cat, A Man, And Two Women is about a divorced couple in a bitter feud over the ownership of an aging feline.

The current wave of interest in cat-related books comes on the back of the rise in pet ownership, a groundswell of anime and graphic novels featuring cats, the existence of numerous cat islands promoted on social media, and the profitable merchandising of cat themes and designs, epitomized by the perennial popularity of Hello Kitty, and an NHK’s rerun of the hit TV series World Cat’s Travelogue.

A former niche, now a growing area of popular publishing, many of the books written about cats, both fiction and non-fiction, are, like Takashi Hiraide’s bestseller, The Guest Cat, available in English and other languages. These include Genki Kawamura’s If Cats Disappeared from the World, Kiyoshi Shigematsu’s The Blanket Cats, Mornings With My Cat Mii, a memoir by the late Mayumi Inabi, and the slightly fabulist, We’ll Prescribe You A Cat by Syou Ishida.

Many readers who are already fond of cats will be predisposed to books like this, whose cozy, reassuring sentimentality evokes the atmosphere experienced while watching early Studio Ghibli anime. The plots in many of these fictional accounts, some of which requisition aspects of magic realism, provide consolation and relief to readers dealing with stress arising from work, social and family problems. A counter to a world consumed by armed conflict, climate disasters, violent crime, social decay and flawed leadership, these works, loosely falling into the iyashikei (healing forms) of literature, generally progress towards satisfying resolutions, in which the human cast experience transformative, life-affirming shifts.

There are also a number of books with Japanese settings by foreign writers. CJ Fentiman’s The Cat with Three Passports, is a heart-warming account of an English teacher’s chance encounter with a homeless cat found on the streets of Takayama. Then there is Nick Bradley’s fictional account of a stray cat wandering the darkly malevolent night alleys of Tokyo, encountering city dwellers struggling with entrapment, loneliness, isolation, and the desperate search for love. The very opposite of the consoling escapist plots offered by cat related novels, such as Toshikazu Kawaguchi’s Before the Coffee Gets Cold series, or another coffee and feline-themed work, Mai Mochizuki’s The Full Moon Coffee Shop, which features a staff of talking cats, Bradley’s realist novel became a surprising bestseller. Bringing a touch of accessible scholarship to the field, Tuttle Publishing has recently brought out a beautifully illustrated title, Divine Felines: The Cat in Japanese Art. Its author, Asian art curator Rhiannon Paget, has no hesitation in asserting that, “Japan is the undisputed epicenter of global cat culture.”

As some of these works point out, it isn’t easy for people who look after cats to describe their role. “Owner” sounds a little too proprietorial, “guardian” and “parent” a bit forced. Many, settle for “caretaker”. Cats have, to some extent, inverted, or subverted, the owner-pet role. The late Carole Wilbourne, a self-described cat therapist, correctly noted that, “A cat is a free spirit and will not be subservient.” Cats, as the old saying goes, don’t have owners, they have staff, people who clean for them, prepare their food, take them on periodic visits to the vet, and perform countless other services. People, in short, who obligingly cater to all their needs.

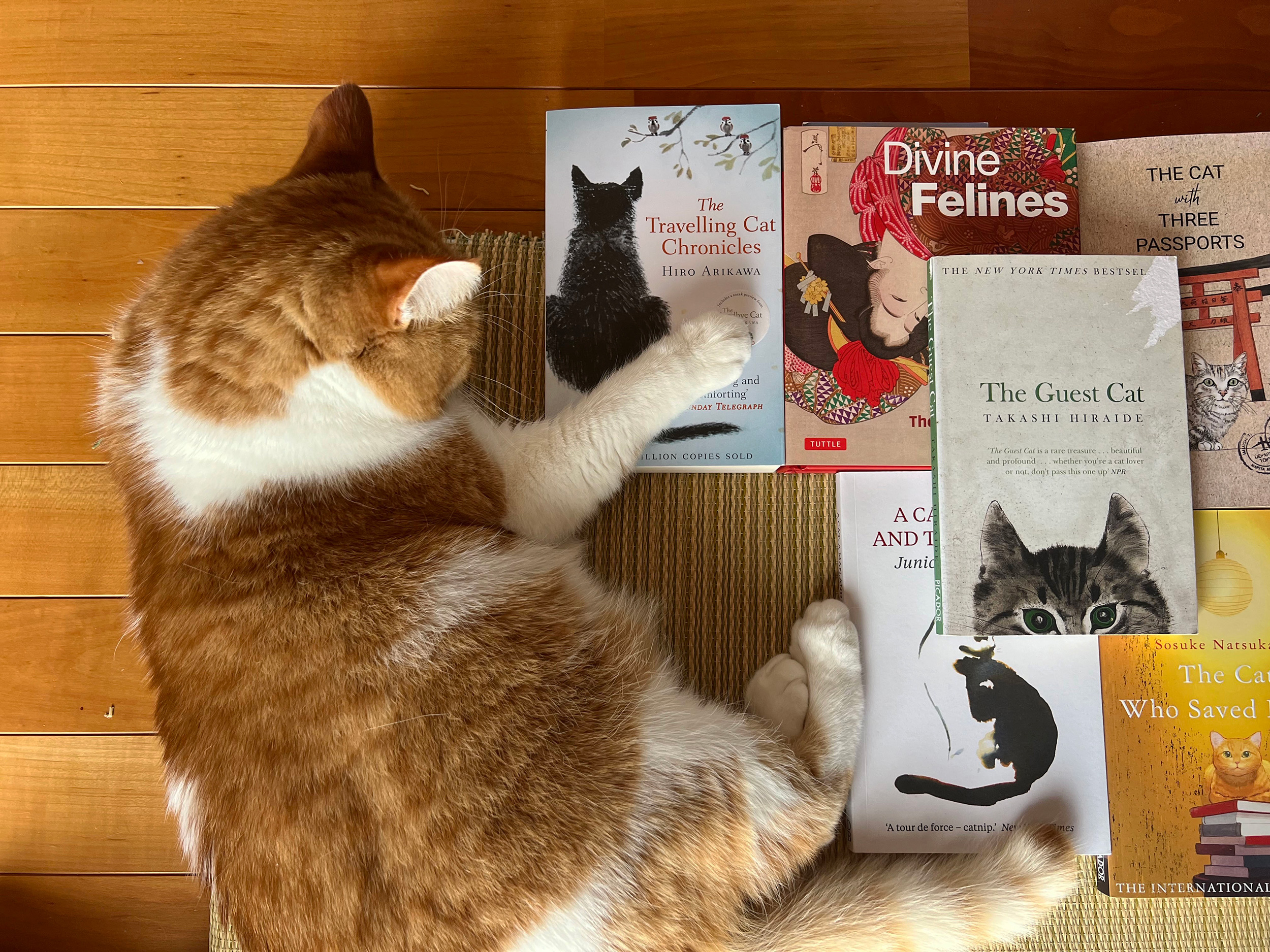

Will the interest in felis catus continue, or is it already reaching saturation point? With increased pet ownership in Japan, the trend is unlikely to decline in the foreseeable future. In the meantime, there are plenty of book titles past and pending to explore. I have yet to read Hiro Arikawa’s The Travelling Cat Chronicles, a novel about loyalty and companionship, or The Cat Who Saved Books by Sosuke Natsukawa. But they are on my list. The novelist Haruki Murakami, the former owner of a coffee and jazz shop called Peter Cat, apparently wrote an engaging essay about his childhood cat that I’m trying to track down.

As the number of works on the subject mount, we may soon need the kind of instincts possessed by felines in following the tangle of paths that wind and bifurcate through the proliferating thicket of cat literature.

Stephen Mansfield is a Japan-based writer and photographer whose work has appeared in more than 60 magazines, newspapers and journals worldwide. He is the author of 20 books.