Issue:

May 2025 | Deep Dive

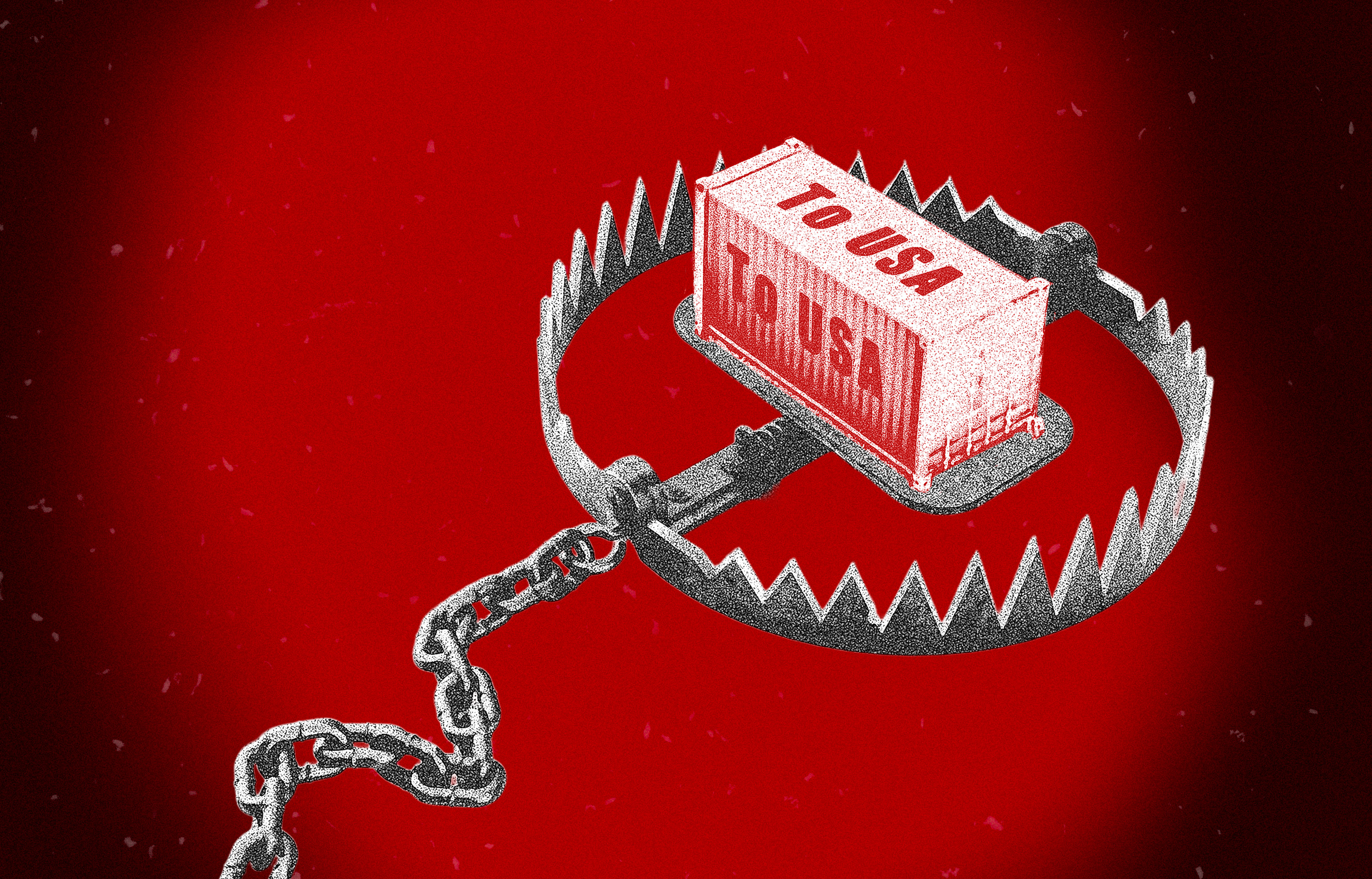

Trump’s tariff wars are a clever ploy, or the catalyst for global recession, FCCJ event hears

There is more to Donald Trump’s “tariff terrorism” than meets the eye, former Harvard economist Paul Sheard claimed during a lively and well-attended Deep Dive discussion at the FCCJ on April 9. The tariffs are tactical rather than strategic, Sheard said, and are a means to an end rather than an end in themselves.

“The idea is to force opponents to come to the table and negotiate pretty quickly, get some concessions and then declare victory and put the tool back in the box,” he said. In “three to six months' time most of the tariffs will be gone” provided the rest of the world makes the kind of concessions Trump is demanding, he added.

Trump’s subsequent announcement that he was exempting a raft of consumer electronics from some of his punishing import tariffs appeared to give credence to Sheard’s claim, but the move was widely seen as an expedient to allow U.S. manufacturers to get up to speed in certain import-dependent sectors.

The Deep Dive took place hours before Trump announced a 90-day reprieve on the imposition of mega tariffs on trading partners that have already offered tariff and other concessions (with the stark exception of China) although a 10% basic tariff has gone into effect on all partners.

Other panelists at the Deep Dive – economist Hung Tran, a non-resident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council Geoeconomics Centre in Washington, and economist and author Richard Katz, were less sanguine about the outcome of the tariff wars, arguing that Trump was deeply committed to using them to change the postwar global economic order.

“I see Trump [tariffs] largely as a symptom of other things that are going on in the global economy or global order,” said Sheard, a former vice president of the financial group S&P Global and author of the Wall Street Journal bestseller The Power of Money.

“I think the predominant system we've had in the post war period, which you might call Pax Americana, where the U.S. behaved as a benign global hegemon, has reached its limits and is starting to come unstuck,” he added. “The U.S. was the country that provided global public goods of security” – keeping the sea lanes open, preserving the liberal trading order and acting as the world’s policeman.

“Particularly when it came to security, the U.S. was providing a disproportionate amount of military spending,” Sheard said.” Military spending in the U.S. is a little bit more than the total of the next nine countries combined. And that's one of the things that President Trump is railing against on the economic side and on the trade side.

“Under the post war system, the U.S. tended to open its markets and not demand reciprocity from other countries, so that many countries have higher import tariffs now than the U.S. does. Trump claims that this is unfair, and has initiated a race to the bottom - or to the top – on tariffs.”

Things have changed since China entered the World Trade Organisation in 2001 and started experiencing massive economic growth. “That's the basic point,” Sheards said. “This is an underlying structural shift in the geopolitical and geo-economic world, which is challenging the sustainability of the Pax Americana system.

"The problem is, we can't expect President Trump to be the one to fix and rebuild this system. Rather than simply railing against Trump’s actions, it is up to the rest of the world to focus on the key issues of how to build a new world order, a world in which there is more joint provision of global public goods.”

Sheard suggested that Trump “wants to have his cake and eat it too. He wants to correct all of these ills that he sees in the system. But he also seems to want to continue enjoying the position of the U.S. as the dominant player in the world. Some would say the chief bully in the world. He hasn't been able to define a real path forward.”

The root of the problem, he added, is that the U.S. president is obsessed with bilateral trade deficits rather than with the gains that America enjoys from trade. ”If we trade across economies, we can leverage more the gains from trade and increase prosperity. Trump sees tends to see [trade] deficits as a drain on national wealth rather than as something that is facilitating it.”

Sheard concluded it was likely that Trump was simply practising “game theory” and playing the tariff card to win the wider game of getting others to share the economic burdens borne mainly by the U.S.

Hung Tran took a different view. “I don't think that in the current administration of President Trump, tariffs are being used only as leverage for negotiation,” said Tran, a former IMF senior official and former chief economist at the Institute of International Finance.

“That may have been the case in the first [Trump] presidency, but this time around, I think Trump is much more ideologically attached to [tariffs] because he wants to have, at the end of the day, balanced trade relationships bilaterally with each of the major trading counterparts.

“It is impossible to do that because, naturally, the structure of the economy and of society and the propensity to save and to consume is different, and therefore you really cannot balance trade bilaterally for every country. Therefore, tariffs will remain because [Trump] will never get all countries to change their society.”

The result, Tran added, will be “stagflation,” lower growth and higher inflation, and more volatility in financial markets.

Katz shared Tran’s view that Trump is driven by ideology and means what he says. He argued that in trying to eliminate the trade deficit, Trump would trigger a severe recession. In fact, this is what might cause Trump to pull back: if rising prices and joblessness cause a backlash among his voter base.

The direction of the dollar is meanwhile unknowable because some of the fallout from the trade war will push the dollar upward, and others will push it downward. Katz said. “No one can say the net impact. The initial impact has been to push the dollar downward as investors fear recession in the U.S.”

Anthony Rowley is a columnist and contributor for the South China Morning Post.