Issue:

IN HIS NEW BOOK, A FORMER CLUB MEMBER AND LONG TIME RESIDENT RECOUNTS HIS SEARCH FOR HIS FAMILY ROOTS AND HIS OWN IDENTITY

Try as we might to be objective, we reporters invariably bring our personal preconceptions and prejudices to the stories we write. Because of Japan’s tendency to set itself off from “outsiders” that strong sense here of “we” versus “they” many of us have a love/ hate relationship with the country. That ambivalence is magnified when you come, as I have, from a family that has lived in Japan as outsiders for 144 years. And it’s magnified even further when, for most of that time, your family, as part Japanese, has never quite fit in.

Working as a young reporter in Japan for Business Week from 1982 to 1986, I never thought of such things. I was covering a trade war, and I was reporting for the American side. But while writing for the Los Angeles Times in the early 1990s, I faced two very personal crises that made me re-examine my attitudes towards Japan. The first was the death of my half Japanese father who had never really found a home in either Japan or America, and had died an unhappy man.

The second was the decision my wife and I made to adopt Japanese children. It seemed natural at first, but I found myself having doubts. I couldn’t explain them at the time, but today I suspect they had something to do with our family’s efforts over the generations to hide our Japanese heritage.

Although we happily adopted Mariko, followed soon afterward by my son Eric, I remained ambivalent toward Japan, and I wondered if I could be a good father with that attitude. That’s what set me on the road to explore my family’s long history in Japan. My book, Yokohama Yankee, is about that journey, about my effort to rediscover the past and to reconcile my Japanese self with my Western self.

Since my family story is so intertwined with modern Japanese history, the book is also about Japan’s efforts, over the past century and a half, to reconcile its national identity with a world so dominated by the West.

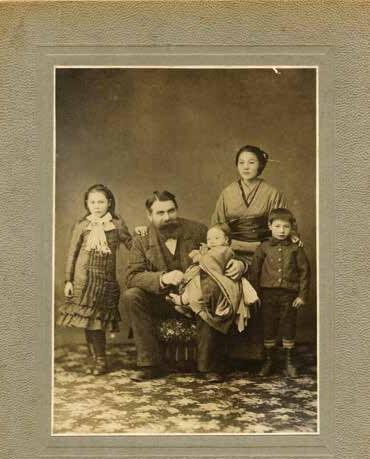

When my German great grandfather arrived in Yokohama in 1869, Japan was hiring foreign experts in a mad rush to catch up with the West. My great grandfather, who had fought in the Austro Prussian War, was hired as a military adviser to a warlord in Wakayama.

Later, he married a Japanese woman and started Helm Brothers, a stevedoring and forwarding company that would grow to be among the largest foreign owned companies in Japan. Twice the company was wiped out together with most of Yokohama: once during the Kanto earthquake of 1923 and again during the fire bombings toward the end of World War II. My grandfather, an American, spent the war in California where the family had to hide their Japanese heritage to avoid being sent to internment camps.

Understanding what happened to my family over that turbulent century helped me to understand my father, embrace Japan and be a better father. It has also forced me to look at Japan’s problems from an insider’s perspective as well as that of an outsider.

Excerpted from Yokohama Yankee: My Family’s Five Generations As Outsiders In Japan (Chin Music Press, 2013)

Just Another Gaijin?

ONE EVENING ABOUT A MONTH AFTER Dad’s funeral, I was browsing the magazines on display at a train platform kiosk when I saw the banner headline on a copy of the Bungei Shunju, an intellectual journal. “Kenbei,” it read contempt for America. I bought it and flipped to the special report. My heart quickened as I began reading the essays. This was incredible! Here were Japan’s leading industrialists and intellectuals declaring that the United States was a nation in decline. The chief executive of a giant electronics company said he wouldn’t buy American semi conductors because they were shoddy. A Japanese novelist said the noble America she had once admired had turned into a self centered bully. An economist advised the United States to focus on its one true expertise: farming.

The next day, I began reporting for an article about this growing disdain for America. My article, In Japan: Scorn for America, appeared in late October 1991 on the front page of the Los Angeles Times and was picked up by newspapers around the world. My editors loved it. A friend at the State Department said President Clinton, who was preparing for his upcoming trip to Japan, had commented on it. I loved the attention.

Two weeks later, I received a packet of letters from readers that had been forwarded to me by my editor. The letters were all about my kenbei story. The first few were complimentary and I smiled, but as I read on, the blood drained from my face.

My heart pounded as I continued to read the letters. The raw anger and hatred they expressed frightened me. Later I heard that anti Japanese grafitti had popped up in parts of Los Angeles. I felt like a child playing with matches who had started a fire he could not control.

grandfather Julie and family;

father Don and mother Barbara;

Had I been fooling myself? I knew Americans regarded their country as the greatest nation on earth. Of course they would be upset. Wasn’t that what made kenbei such a good story? Ever since the end of World War II, Japan had played the role of obedient disciple to its American teacher. Now, it seemed, Japan was coming into its own. It was a legitimate story. And yet, I had a naging feeling. Was I simply reporting a trend or was I venting some deeper personal hostility toward Japan?

Distracted for the rest of that day, I left work early. Since my wife Marie was still in Seattle, I took the subway three stops to the Foreign Correspondents’ Club to grab dinner. The Club was on the twentieth floor of an office building on the edge of Ginza, a popular shopping district. Visiting dignitaries gave press conferences at the club. Reporters met with sources for dinner or drinks.

I walked to the bar and sat at the “correspondents’ table” where a few regulars gathered. Sipping our beers, we discussed the latest news: perhaps it was the story about the latest politician to deny Japanese soldiers had ever massacred civilians in Nanjing, China. I can’t remember. What I do remember about that night was a distinct shift in how I looked at myself and my role as a reporter. I had always felt a sense of esprit de corps among these foreign correspondents a feeling that we were a special breed reporting an important story. Now I felt disengaged. Weren’t we just cycling through variations on the same tired story about Japan’s insular ways? The intimacy I felt toward my fellow reporters was real, but the sense of community was not. We were like members of a packaged tour. We enjoyed being together, but when the tour ended, we might never see each other again. So if this wasn’t my true community, what was? Lodged uncomfortably at the back of my mind, like a tiny pebble caught in a shoe, was the reality that my father had died at sixty four without ever finding a place where he belonged.

After dinner, I took a detour home through Shibuya, the heart of Tokyo’s busy entertainment district. I followed the crowd off the train, down the stairs and out the turnstiles. I stopped at the pedestrian crossing, but more people kept coming from behind, and soon I was packed as tightly on the sidewalk as I had been on the train. I gazed up to see a teen idol dance across a fifty foot screen that dangled on the other side of the street some where between heaven and earth.

When the light turned green, we surged forward, and for a moment, as a wall of people moved toward us from the opposite side, we looked like two armies converging in battle. I slipped away from the crowd down a narrow lane. I walked past restaurants and bars whose kitchens pumped out smoke that smelled of grilled fish and burnt soy sauce. An old fortune teller who always placed her small table in the middle of the lane, split the flow of pedestrian traffic like a rock in a stream. Her wrinkled face, bowed low over the table, reflected the yellow light of her square paper lantern.

At an electronics store, I stopped to look at a long row of television screens where a boyish looking man with a blue blazer, scruffy brown hair and goggle eyed glasses stood frozen, staring out from a passing stream of grey suited salarymen. It took a moment for me to realize that it was my face being captured by the store’s camcorder.

“Irasshai, irasshai (welcome)” shouted a young salesman. He put his back to me as he tried to lure passersby into the store. I walked on to an area where every surface telephone booths, utility poles, walls and ground was plastered with small flyers advertising prostitutes. If I had been of another generation, I might have called one of those phone numbers. If I climbed a low hill to the left, I would have found myself on one of the quiet, dimly lit streets that surrounded this entertainment district. There, in a love hotel that charged hourly rates, I could have had a private rendering of Shibuya’s flashing, thumping sensory sea.

Shibuya was the mecca for Japan’s youth, but I was neither Japanese nor young. Perhaps it was the unexpected raction to the kenbei article. Or perhaps it was Dad’s recent death. Whatever the reason, I felt as if I had been let loose from my mooring and was drifting rudderless.

Leslie Helm is editor of Seattle Business magazine (www.lesliehelm.com)