Issue:

November 2021

New film tackles taboo of Japan’s wartime quest to build a nuclear bomb

This month, American movie audiences will be challenged with a strikingly counterintuitive historical narrative: Japan’s attempt to build a nuclear bomb.

The fevered American race to build the bomb during World War II infamously ended in an airburst 580 metres above Hiroshima that killed 140,000 people and incinerated the city on August 6, 1945. The destruction of Nagasaki and another 70,000 lives followed three days later. Less well known is that wartime Japanese scientists were trying to develop a similar weapon.

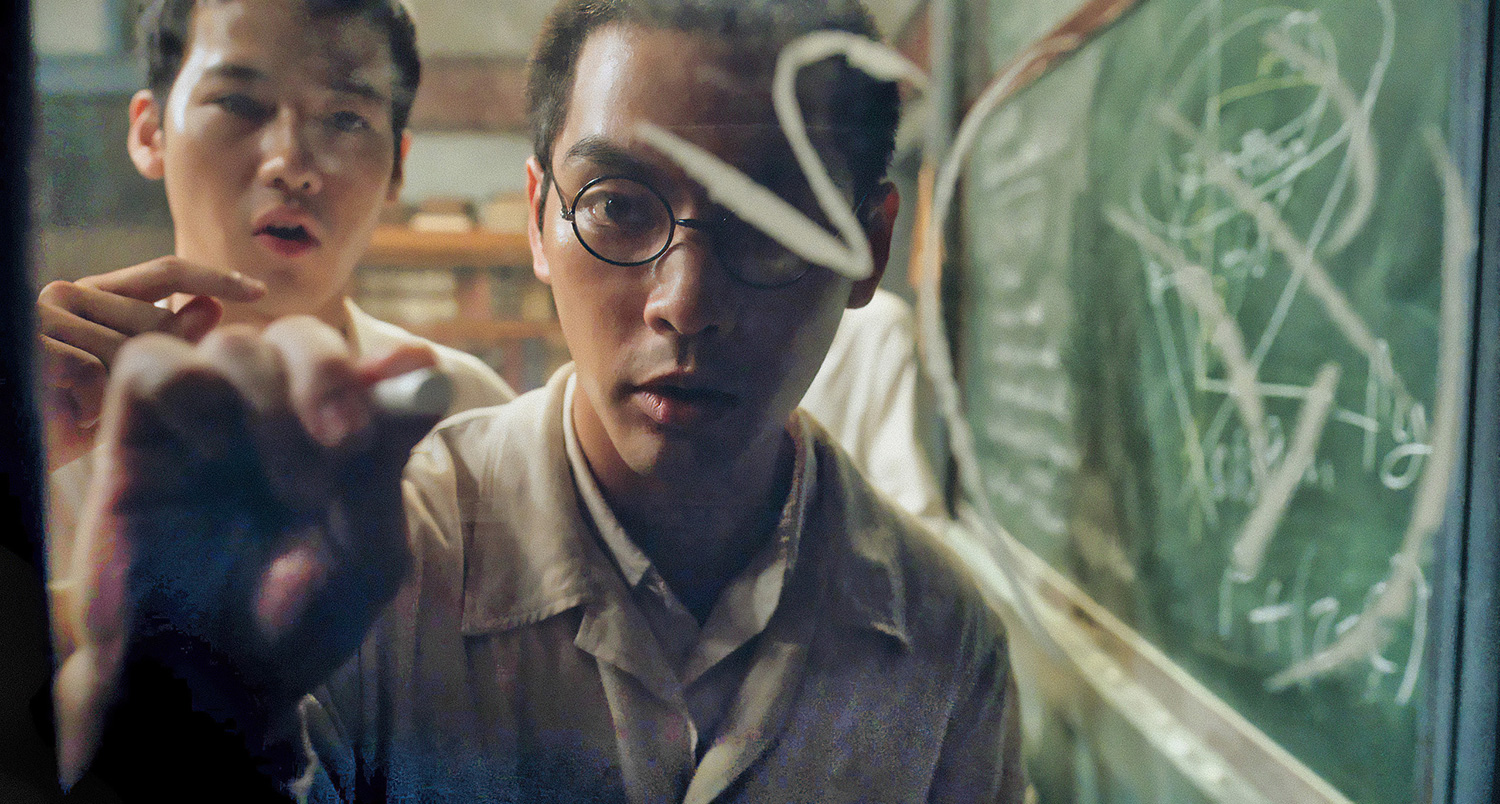

The Japanese movie Taiyo no Ko (Gift of Fire) for the first time dramatizes that history, depicting the project at Kyoto University, led by physicist Bunsaku Arakatsu, a brilliant protégé of Albert Einstein. The FCCJ first screened the movie in July, followed by a Q&A with director Hiroshi Kurosaki and the movie’s LA-based producer Ko Mori.

“The Film Committee is especially pleased when we can highlight a newsworthy international coproduction, and allow our audiences to engage directly with the filmmaking team,” said Karen Severns, who runs the committee. “The filmmakers are always thrilled to have a chance to hear from non-Japanese audiences, since the range and depth of questions is quite different.”

The Imperial Japanese Navy ordered an initially skeptical Arakatsu to build a bomb in 1942. A separate bomb project, commissioned by the army, was undertaken in Tokyo under Yoshio Nishino, known as the father of nuclear physics in Japan.

With its vastly greater resources, the U.S. tested the first atomic bomb in New Mexico in July 1945 before unleashing the weapon on Japan, which surrendered a few days later. The U.S.-led Occupation forces destroyed the rudimentary laboratory equipment in Kyoto and Tokyo, and consigned Japan’s A-bomb program to history.

Gift of Fire opened at 250 cinemas across Japan in August and is set for release in the US this month. The story is little known abroad, according to Kurosaki, or even in Japan, where few young people know what happened. “There is a sense that this is hidden history and many are surprised to learn it,” said Kurosaki, who spent 10 years trying to finance his film.

The history isn’t actually secret, Kurosaki said. “All the information is freely available but it’s in academic studies, not in novels or movies.” His research began when he found the remains of a young scientist’s diary in a Hiroshima library. I researched from off-the-shelves books in the library. It’s just that almost nobody wanted to tell the story, and that aspect I found really interesting.”

Kurosaki hangs his tale on a group of idealistic young scientists under Arakatsu, who says their task is to “release the power of the atom”. The work is given urgency by the war raging outside their cloistered circle. Nearly everyone has family fighting abroad. Newsreel footage shows kamikaze pilots (many in their teens) crashing planes into enemy ships in a doomed attempt to repel the American invasion.

The central character, Shu Ishimura (Yagira Yuya), must also watch his beloved younger brother, Hiroyuki (Haruma Miura’s last role before his tragic suicide) march off to war.

Shu spends much of his time trying to source scarce uranium nitrate from a local potter who uses it to dye his urns. The scientists develop a series of cyclotrons, charged particle accelerators used to isolate isotopes present in the uranium – the first step toward nuclear fission.

During a U.S. air raid, the scientists debate their research. “If we dropped the bomb on San Francisco an estimated 200,000 people would die,” says one. “300,000,” he is corrected. “If we don’t build it the Americans will; if they don’t the Soviets will,” says another. When someone questions the ethics of their work a young engineer angrily shouts: “My brother died. I don’t want his death to be in vain.”

Later, Ishimura is shown walking among makeshift funeral pyres burning great piles of bodies in Hiroshima’s blasted landscape. “This is the reality of what we are trying to achieve,” he muses darkly. Arakatsu seems to have his eyes set on the world after the fighting stops. Wars are fought for energy, he says. If scientists can create unlimited energy, it might take away the reason to fight.

Japan never came close to enriching enough uranium to make a weapon – just one of the technical problems it struggled to overcome. A German Nazi submarine attempting to deliver a large cache of uranium oxide to the Japanese military was captured in 1945.

Postwar Hiroshima became what writer Ian Buruma calls the centre of “Japanese victimhood,” the site of pilgrimages with the “atmosphere of a religious center”. Millions of schoolchildren have made that pilgrimage, but their textbooks spend little time dwelling on the darker aspects of Japan’s war.

The movie could hardly be timelier. In January, the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists put the hands of their Doomsday Clock to 100 seconds before midnight, the closest it has been to symbolic doom in its 70 years of existence.

In April, Japanese government officials shocked anti-nuclear campaigners by opposing a proposed U.S. policy of no-first-use of nuclear weapons. Despite its official anti-nuclear stance, Japan continues to not only shelter under the U.S. nuclear umbrella, but quietly lobbies for a tougher stance against nuclear-armed China and North Korea.

There is nothing new in that. Japan’s ambiguity on nuclear weapons began almost as soon as they were developed by Russia and China.

“It would be tragic if Japan, the only country to suffer nuclear attacks, and a staunch advocate of the abolition of nuclear weapons, blocked this small but important step toward the abolition of nuclear weapons,” said a group of scientists and activists.

Kurosaki says it’s time to study history. “After the war, I think that the fact that Japan was a victim of nuclear weapons but was trying to develop one itself became a taboo. I think it is important to face that contradiction.”

David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for The Independent, The Economist and The Chronicle of Higher Education.