Issue:

By Torin Boyd

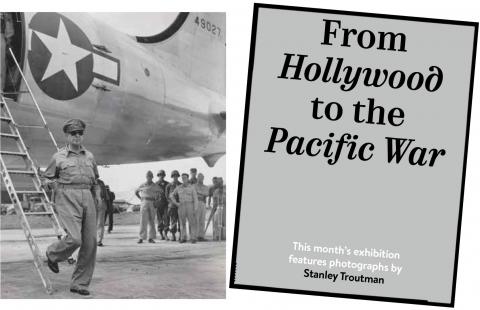

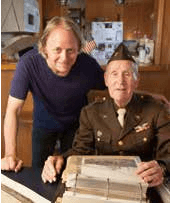

This year marks the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II, and the loss of another war photographer who worked in the Pacific theater. Stanley Troutman, who also photographed the golden era of Hollywood from the late 1930s, passed away on Jan. 2, 2020 at age 102.

Troutman was born in Pasadena on Oct. 3, 1917 and grew up in the Echo Park neighborhood of LA. He used funds from his first job to buy a 4x5 Speed Graphic, hoping to enter into the photography business. At 20 years old, he got his first break when a neighborhood friend and former childhood movie star helped him land a job at the LA bureau of Acme Newspictures in 1937. As was common in those days, Troutman started out as a darkroom assistant, something he referred to as being a “hypo bender.”

Earning $16 a week at the start, the 20-year-old Troutman worked his way up to a staff position. Within a year he was covering Hollywood photographing stars like Bing Crosby, Marlene Dietrich, Ginger Rogers, Charlie Chaplin and Frank Sinatra.

When the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred on Dec. 7, 1941, Troutman was 24 years old. He was considered exempt from service due to his status as a journalist, something the war department deemed vital to the home front. In 1944, however, he volunteered to be a war correspondent. Embedded with the Wartime Still Picture Pool which included LIFE Magazine, AP, International News Photos and Acme, he entered the Pacific war armed only with a camera. He explained, “cor- respondents were not allowed to carry a gun. If we were captured, we could be shot as spies”.

His first assignment was the Battle of Saipan in June 1944 where he worked alongside LIFE Magazine photographer

W. Eugene Smith, who mentored him. After Saipan, Troutman covered the battle of Tinian Island, followed by the invasion of Peleliu where Troutman made some of his most memorable images of the war. Then on to Guam, Borneo and the Philippines, where he encountered more heavy fighting. He had a close call during the invasion of Corregidor on Feb. 17, 1945, the second day of the invasion. Although it was supposed to be safe, his landing craft came under fire. Said Troutman, “There were fourteen of us on the boat and three Marines were killed. When the ramp finally went down, I got onshore and as they were unloading a truck, it hit a land mine and exploded.”

After a year of covering the war, an exhausted Troutman returned home for some badly needed R&R. Acme then assigned him to an around the world press junket on General Jimmy Doolittle’s B-17 bomber. On a visit to Dresden, Germany, Troutman got a preview of the devastation he’d soon be witnessing in Japan.

Troutman found himself back in the Philippines in mid August after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. His route to Japan took him through Shanghai, where he photographed the liberation of the Chapei internment camp.

He arrived in Japan on Aug. 30 on the second US plane into Atsugi Airfield, in advance of General Douglas MacArthur who arrived later that day to full fanfare. While at Atsugi, he was given a tour of the kilometers of tunnels underneath the airport, proving just how prepared the Japanese were for an attack on Honshu.

His next assignment was the Japanese surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2. Troutman had a camera position reserved for the ceremony, but on the morning of the surrender, he was informed he was cleared to fly to Nagasaki.

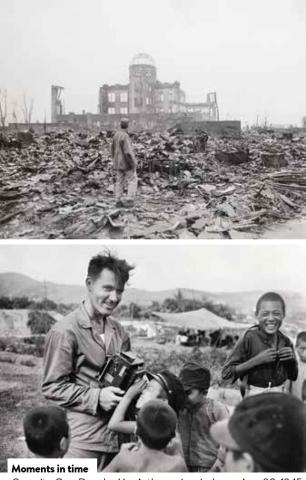

Forced to choose between the surrender or Nagasaki, he chose the latter. It was a time when General MacArthur was grounding correspondents trying to report on Nagasaki and Hiroshima by limiting fuel, but Troutman and the press pool scrounged up enough fuel to make the 900 kilometer flight to Nagasaki, making him one of the first journalists to enter the city.

A visit to Hiroshima followed on Sept. 6 when Troutman and the AAF press pool were given access to the city’s apocalyptic landscape. As they drove into the city, they noticed how the bomb had created a ripple effect in the landscape, like when a pebble strikes a pond. Not briefed in the dangers of radiation, Troutman was more concerned about it ruining his film. His tour of the city resulted in an iconic image of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, now commonly known as the Genbaku Dome. Other stories that Troutman covered in Japan included bombed out Tokyo and the ruins of aircraft factories in Nagoya.

By the end of September 1945, Troutman was back home with his family settling into postwar life. He became disillusioned with Acme, and took a job with the University of California Los Angeles’s publicity Department in 1946. Working as a photographer for UCLA afforded Troutman a chance to do everything from filming football and basketball games to publicity portraits. Some of the people he photographed there included coaches Red Sanders and John Wooden, a young Arthur Ashe, and future Olympic gold medalist Rafer Johnson. The school also sent him to cover the 1956 Summer Olympics games in Australia. Troutman remained at UCLA until his retirement in 1980. After retirement, he was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Press Photographer’s Association of Greater Los Angeles in 2004. The PPAGLA also set up an endowment award in his name for excellence in sports photography.

Photojournalist Torin Boyd has been based in Japan for over thirty years and is affiliated with Polaris Images.