Issue:

June 2022

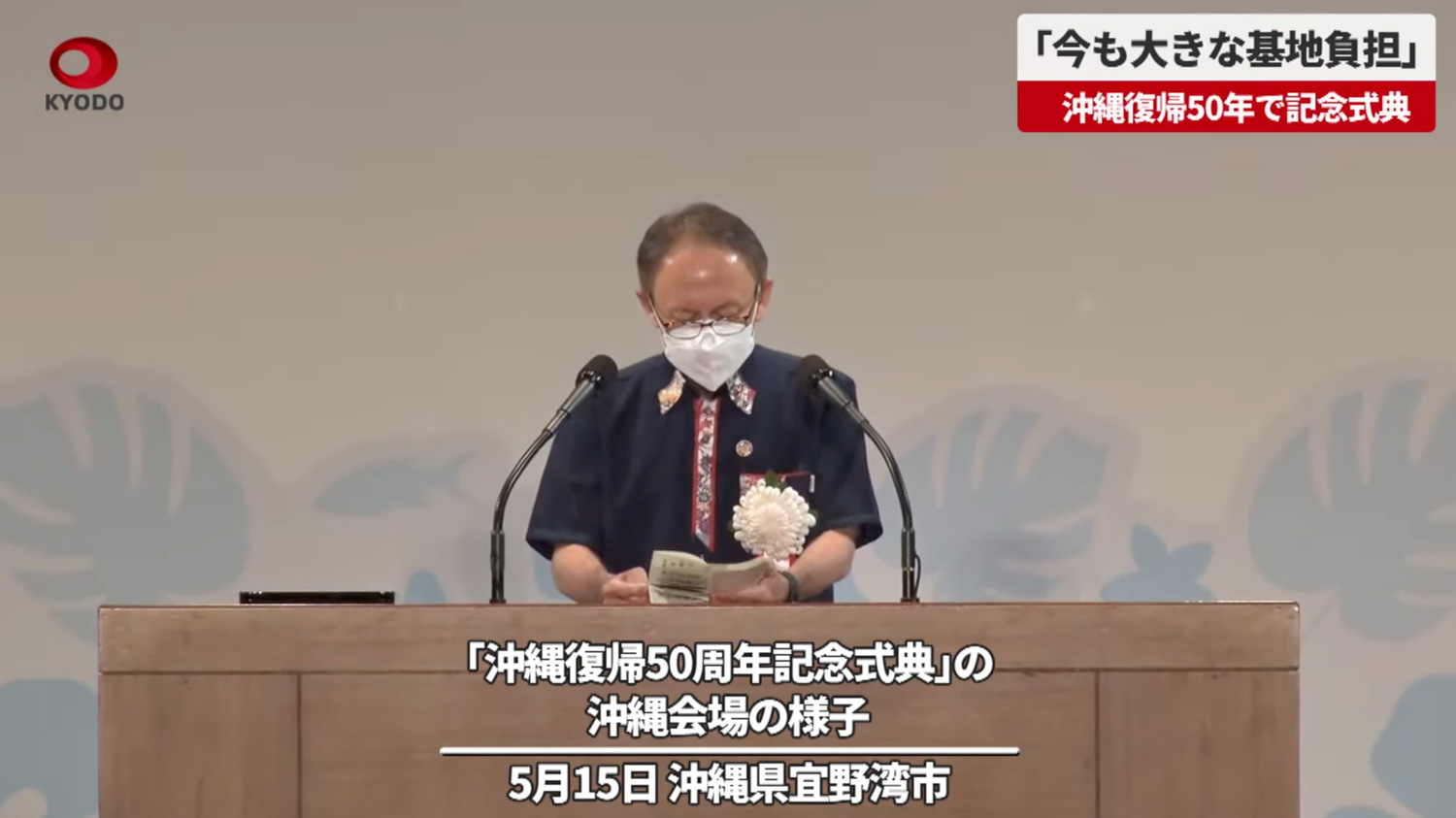

Heavy base burden rankles on 50th anniversary of reversion

Okinawans found little to celebrate in marking the 50th anniversary of reversion to Japanese control in 1972. There is widespread disappointment because of festering grievances as Okinawa continues to bear a disproportionate base hosting burden. In addition, Okinawa is Japan’s poorest prefecture, with income about 70% of the national average, and employment opportunities remain limited.

A Kyodo News poll at the end of April found that 55% of Okinawans were dissatisfied with the post-1972 “course of history”, although 94% welcomed the reversion to Japanese rule after two decades under US military administration. The poll found that 58% favored significant downsizing of the bases, 14% wanted them removed and just 26% favored the status quo. https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2022/04/0323d62dc7bc-55-of-okinawans-unhappy-with-50-yrs-since-reversion-to-japan-poll.html

The 72% anti-base sentiment in this poll is similar to the prefecture-wide referendum in 2019 against building a new base in Henoko, a result that Tokyo has steadfastly ignored. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/24/okinawa-referendum-rejects-new-us-military-base-but-abe-likely-to-press-on

Shared values and flawed strategy

While political leaders in Washington and Tokyo regularly cite shared democratic principles, Okinawans’ longstanding support for downsizing the US military presence has been disregarded in bilateral security deals. Invoking the nostrum of shared values in public discourse provides background music while Washington pressures Tokyo to dance to its tune. Yet, this lack of democratic legitimacy for US-Japan security policies in the prefecture is more than a nuisance, and unsustainable on both strategic and ethical grounds.

The blueprint for reducing the U.S. military footprint in Okinawa, the so-called 1996 Roadmap, is a relic long on unfulfilled promises that has not eased the base burden. In 1972, 58% of the landmass occupied by U.S. military forces in Japan was in Okinawa, but now that figure has risen to 70%. The U.S. military currently occupies 18% of Okinawa’s main island, and the prefecture is where about 80,000 Americans live, including nearly 30,000 active-duty military personnel – more than half the total based in Japan. In 2016, the U.S. finally returned a paltry 10,000 hectares of land used in the Jungle Warfare Training Center, 20 years after agreeing to do so, yet another gesture in the “too little, too late” category.

The U.S.-Japan Alliance shifts much of the burden onto Okinawans without their consent. In addition, there is little more than vigorous handwringing concerning environmental degradation and longstanding grievances about sexual violence by American servicemen. Rising regional tensions make it difficult to imagine that policy wonks or politicians will move to ease the burden. China’s hegemonic ambitions, and a threatening North Korea, are yet again thrusting Okinawa into the crosshairs of geo-strategic maneuvering. From the U.S. perspective, Okinawa is the keystone of the Pacific due to its location at the crossroads of competing claims in the East China Sea and China’s naval gateway to the Pacific. But this strategic imperative does not convince Okinawans that they need to do more; rather, it reinforces a sense that the rest of Japan has not done enough.

On an NHK special on reversion aired on May 12, Fumiaki Nozoe, a professor at Okinawa International University, noted that Okinawans main grievance is the unfair base hosting burden. Rising regional tensions mean that the rest of Japan must shoulder more of the security burden and not always outsource this to Okinawa he said. Even though crimes committed by American servicemen in Okinawa may have declined since reversion, Nozoe noted that in the context of accumulating frustration, each new incident sparks outrage. Tokyo, he said, doesn’t seem to understand why locals are so exasperated. Indeed, for many other Japanese, it is an “out of sight, out of mind phenomenon”, ensuring the central government only feigns concern.

The problem is that building new bases outside Okinawa comes up against determined NIMBYism, so the central government continues to back a risky concentration of US bases. From a security perspective, the overconcentration of bases renders them vulnerable to an attack that would seriously impair how US forces could respond or make a difference in a regional conflict, ostensibly the reason for being in Okinawa in the first place. It makes more sense to disperse these military assets around the archipelago.

That is unlikely to happen due to NIMBYism, path dependence and indifference, a default mode that stokes local opposition to not only the bases but also existing and pending missile deployments in the prefecture. Locals view the bases as tempting targets and thus believe that a worsening risk environment is all the more reason for the rest of Japan to step up. They understand why it was impossible for the central government to find any towns in mainland Japan willing to host the Aegis Ashore batteries in 2020 because they are likely targets. They also understand that a Taiwan contingency (China invading or sabotaging the island’s autonomy) is a Japan contingency looking for a solution in Okinawa, otherwise known as “frontline deterrence”. Miyakojima, very much on the front line in the westernmost chain of islands in the archipelago closest to Taiwan, now hosts SDF missile batteries with a 200 km range and future deployment of US intermediate range missiles there is probable. On a visit to Miyakojima in April, it was clear there is some opposition, but also resignation about the missiles, a fatalistic recognition that Tokyo gets what it wants. Next up is basing SDF aircraft at the island’s Shimoji airport, even though the government promised it would never deploy military planes there when it was built. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has provided political cover for breaking this promise, as do Chinese naval patrols off the cost of Miyakojima. On Ishigaki island, there are plans for SDF missile deployment next year, but opposition appears widespread. Fields around the island were festooned with banners expressing opposition to the planned missile deployment and islanders were organizing to challenge this diktat from afar.

Prospects for a regional conflict makes policy wonks in the US and Japan even more eager to maintain and augment America’s presence in Okinawa and expand that of the SDF. As Nicholas Szechenyi at CSIS explains: “Okinawa is an extremely important location for the US-Japan alliance to evolve, together. Because that jointness is our greatest strength.” https://asia.nikkei.com/Editor-s-Picks/Interview/When-it-comes-to-deterrence-Okinawa-sits-in-the-right-place

Alas, Okinawans are on the outside looking in on this “jointness”. When security experts speak of the need to creatively manage local opposition to this agenda, it doesn’t mean altering such plans but rather figuring out a way to proceed. Opponents are an irritant to overcome, a sidelining well within Washington’s and Tokyo’s comfort zone.

Public works spending is one way that Tokyo compensates Okinawa for the troubles associated with the U.S. bases. The second segment of NHK’s special on reversion (May 13) found, however, that massive funding of infrastructure projects has not generated much economic momentum, and instead Tokyo had nurtured a subsidy addiction and from the 1990s squandered vast sums on a slew of white elephant projects.

No to Henoko

The Henoko replacement facility now under construction as a replacement facility for the Futenma U.S. Marine Corp Air Station located in densely populated Ginowan City is another of these white elephants, one that Tokyo is imposing on Okinawa. Back in 1996, the government decided to build a V-shaped runway on reclaimed land in Oura Bay on top of a coral reef in pristine waters. Okinawa islanders oppose this plan because it’s not immediately obvious why reducing the U.S. military footprint requires building an additional new military facility in the prefecture rather than somewhere else. Okinawa’s political leaders have tried various means to block the project, but to no avail.

In a series of elections and public opinion polls, Okinawans have rejected the Henoko plan, but the democratic will of the islanders has been subordinated to the alliance. Denny Tamaki won a thumping landslide victory in the 2018 gubernatorial elections by promising to continue the fight against Henoko, yet another embarrassing setback for the Abe government. Team Abe was further displeased by Tamaki holding a prefecture-wide referendum in February 2019, in which 72% of Okinawan voters gave the thumbs down to the Henoko relocation plan. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/feb/24/okinawa-referendum-rejects-new-us-military-base-but-abe-likely-to-press-on

Subsequently, in a nationwide poll conducted by Kyodo News in March 2019, 69% said the central government should respect the results of the referendum, while only 19% said there is no need to do so. https://www.nupoliticalreview.com/2019/03/20/ending-the-okinawa-conflict-a-challenge-for-democracy/

Even so, Abe and his successors have bulldozed ahead, dumping rocks and sand into the bay, killing the coral and degrading the environment needed for marine life in the area. The geology of Oura Bay, however, is unsuitable for the runway project as a government survey in 2016 found the sea bottom has the consistency of mayonnaise, ensuring higher construction costs and further delays. In the Keystone of the Pacific, this is the deeply flawed bedrock of the alliance where expediency trumps shared values. The least-bad temporary solution still appears to be shifting Futenma’s operations to the massive Kadena Air Base, but intra-service rivalry is blocking this. In 2011, Senators Carl Levin, Jim Webb and John McCain backed that plan, dismissing Henoko as “unrealistic, unworkable and unaffordable”.

While a 2019 East-West Center study finds somewhat more positive attitudes overall about the U.S. military presence among younger Okinawans, they also express strong resentment about the disproportionate base hosting burden. The study concludes that “[t]he construction of a replacement base at Cape Henoko is widely regarded as a betrayal of Okinawa to broader Japanese interests and prejudices.” https://www.eastwestcenter.org/news-center/east-west-wire/new-ewc-report-reveals-attitudes-younger-okinawans-toward-us-base

Robert Eldridge, an academic who served from 2009-2015 as an advisor to the U.S. Marines, was a prominent advocate for the bases who has since recanted. In his view, the Henoko base relocation project, “does not meet the requirements of a 21st century alliance or even a modern-day relationship with local citizens”. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2018/02/13/commentary/japan-commentary/four-mottainai-okinawan-affairs/

His apostasy on the bases provides a damning indictment by an insider sympathetic to the U.S. presence.

A profound betrayal

Reversion was realized in 1972, but for many Okinawans it was a diplomatic deceit that constitutes a profound betrayal as the continuing base presence means that they only regained a semblance of sovereignty. Contemporary pacifism and anti-base sentiments draw on local rancor about what can go wrong when Okinawans get caught between larger, distant forces pursuing agendas at odds with islanders’ interests. Now that tensions with China are ratcheting up, many islanders feel as though they are being used as sacrificial pawns once again just as in 1945. The question confronting policymakers is whether it is wise to make Okinawa an inviting target by concentrating US forces there and whether riding roughshod over local sentiments is a sustainable model consistent with so-called shared values.

Jeff Kingston is director of Asian studies at Temple University Japan.