Issue:

June 2022

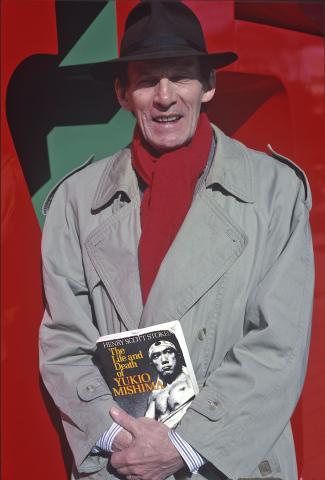

Remembering Henry Scott-Stokes

When former New York Times Tokyo bureau chief Henry Scott-Stokes died in April, some colleagues remembered a journalist who was long regarded as an authority on Japan and East Asia. But Scott Stokes also left a legacy of attempting to portray Japan’s wartime actions as those of a benevolent liberator. He also denied Japanese military atrocities at Nanjing, joining Japanese “revisionists” who have made similar assertions.

Scott-Stokes’ 2013 book in Japanese, Eikokujin Kisha Ga Mita Rengokoku Sensho Shikan No Kyomou, was a bestseller, moving over 100,000 copies. Later published in English as Fallacies in the Allied Nations' Historical Perception as Observed by a British Journalist, it contains a number of statements that are, to say the least, surprising for someone who worked for The Financial Times and The Times, as well as The Gray Lady.

“The Tokyo Trials were a total sham, serving only as a theater for unlawful retribution,” he wrote in Fallacies. “And as for the ‘Nanking Massacre,’ there has not been one shred of evidence attesting to it. However, the Chinese are hell-bent on using foreign journalists and corporations to spread their propaganda throughout the world. There is no point in even debating the comfort women issue.” Later in the book he quotes Indian nationalist Chandra Bose, who cooperated with Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany, as saying “Japan was the light of hope in Asia” in struggles against Western colonialism.

The above excerpt is taken from the English translation of Fallacies. It’s copyrighted by the Society for the Dissemination of Historical Fact, a nonprofit “revisionist” group whose honorary chairman, Hideaki Kase, wrote the foreword. Scott-Stokes’ association with rightwing figures is not surprising. His best-known book, The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima, was based on his long friendship with the novelist and radical who killed himself after a disastrous speech to Self-Defense Forces personnel that was meant to spark a coup d’état. He hails Mishima’s “vast, immoral courage” but acknowledges his “fascist tendencies.” He later writes in Fallacies that Mishima’s manifesto, which called on the Japanese military to suppress antiwar demonstrators, was “right.”

But the Japanese version of Fallacies caused a stir not only for denying the Nanjing Massacre but for the author’s own reaction to it. The book was based on numerous conversations with translator Hiroyuki Fujita. Scott Stokes was not a proficient reader of Japanese and the book’s contents apparently surprised him. He was quoted by Kyodo News as saying he was unaware that it asserts the Nanjing Massacre did not happen. In an interview for the Number 1 Shimbun in April 2014, he made comments in a similar vein: “The stance I take is that ghastly events occurred in Nanjing,” he told David McNeill. “Responsibility lies with the Japanese military, Chinese military and Chinese Communist Party. And to know the details of what happened is largely impossible.”

The following month, however, Fallacies’ original publisher Shodensha issued a statement that attempted to address any contradictions: “The author’s opinion is: The so-called ‘Nanking Massacre’ never took place. The word ‘Massacre’ is not right to indicate what happened.” Around this time, journalist Angela Kubo was busy transcribing Scott-Stokes’ chats with Fujita. She quit the project over concerns about the interviews. “It seems that words are being put into Henry’s mouth and that the interviews don’t reflect his real opinions or thoughts,” she wrote in a resignation message that was later posted publicly.

“As to the contents of the Japanese version and the English version, both reflected Henry's views,” Fujita told the Number 1 Shimbun. “The controversy of the Kyodo report about the book was intentionally fabricated to make it seem as if Henry's views were different from my translation.”

On the whole, Scott-Stokes’ views on Japan’s wartime actions seem to be basically consistent: the Empire of Japan was a liberator and unjustly victimized. They are similar to the historical narrative on display at the Yushukan museum at Yasukuni Shrine, which honors the spirits of Japan’s war dead including more than 1,000 people condemned as war criminals.

“My father regarded Nagasaki and Hiroshima as war crimes,” says Scott-Stokes’ son Harry Sugiyama, a broadcaster and television personality. “He felt very strongly about this.”

Scott-Stokes was suffering from advanced Parkinson’s, a degenerative motor disease that can cause communication and cognitive problems. But even in his final years, that didn’t stop him from being credited with authorship of several other books in Japanese including three published in 2020 alone. They range from cheerleading exceptionalism, such as Japanese Culture: Incomparable in the World, as Observed by a British Journalist (2016), to provocative “revisionist” histories, such as Japan Was a Victor Nation in the Great East Asia War: “The Pacific War” is America’s Brainwashing (2017).

To people in the West who have heard of Mishima today, Scott-Stokes’ biography of his hero will be relevant. To others, his views on wartime Japan are his ultimate legacy.

“Henry said he will be responsible for the contents of his books,” says Fujita. “As a journalist, he presented his views proudly despite the fact that almost all other journalists disagree with him. He was certainly a man of conviction. He made a difference in that respect, compared with all the rest of the journalists.”

Tim Hornyak is a Canadian writer based in Tokyo. He has worked in journalism for more than 20 years, and written extensively about technology, science, culture and business in Japan, as well as Japanese inventors, roboticists and Nobel Prize-winning scientists.