Issue:

June 2022

Remembering Henry Scott-Stokes

Described in one recent editorial, as the “darling of the Japanese rightwing,” it’s true that, among those I have counted as friends in Japan, the recently deceased Henry Scott-Stokes was the most conservative by far.

Used by elements of Japan’s rightwing to lend a degree of respectability to revisionist views of history, his later years were tarnished in many eyes by the publication of a book in which he purportedly defended Japan’s invasion of Asia and raised questions regarding the accuracy of reports on the Imperial Army’s conduct during the Nanking Massacre.

Shocked by the conclusions of the final work, in which he claimed his statements were distorted, Henry, whose reading of Japanese was rudimentary, subsequently retracted many of its assertions, only to withdraw the denials, replacing them with vague misgivings. This suggests, in my admittedly biased view, that Henry’s state of mind in his last years, impaired by ill health, allowed him to be easily duped into lapses of judgement.

If Henry cultivated two carefully crafted, co-existent personalities, the political animal and the cultural one, it was the latter I best recall. An Englishman with a faintly patrician manner, a monarchist with a love of the Rolling Stones, a conservative who became the artistic director of a major avant garde installation project, Henry wore many hats.

Born to a Quaker mother and Catholic father, his family were of West Country stock. Some, including a painter who was a member of the Bloomsbury group, were artists. For those not privy to the arcane distinctions of the English class system, there is a type, a small, well- established group, known, affectionately for the most part, as the rural gentry. It was among this social cell that Henry grew up.

After graduating from New College, Oxford, where he studied philosophy, politics and economics, he joined the Financial Times newspaper, eventually serving as its Tokyo Bureau Chief in 1964. He went on to occupy the same post at The Times of London and the New York Times. A prescient journalist, he was able to persuade skeptical senior editors at the Financial Times, that Japan was the biggest economic story on the planet. It was at this time that he began to seek out and associate with writers and artists, realizing that such people finding in their company a unique perspective on Japan. Among the figures he met was the English writer and journalist Angela Carter, scholars Ivan Morris and Edward Seidensticker, and the Japanese novelist Kobo Abe.

While working on a story one afternoon in the offices of The Times of London, a startled Henry was visited by the nationalist writer Yukio Mishima, who declared, "You are the first person to take me seriously". Although Henry’s 1974 biography, The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima, makes no mention of the incident, it was a telling encounter. Mishima appears at some indeterminate time to have elected the man from Somerset as one of the persons best suited to oversee the reported facts of his life, and, as fate would have it, his death.

In one of our meetings at his rental apartment in Roppongi, Henry showed me a number of letters received over the years from Mishima. In the last one, dated 4th October, 1970, a month before he shocked the nation by committing ritual suicide at a Self-Defense Forces headquarters in Tokyo, Mishima refers to his novel, The Decay of the Angel, the final work in his Sea of Fertility tetralogy. The last line of the letter concludes, “Finishing the long novel makes me feel sometimes as if it will be the end of the world.”

In a Japan Times interview, I asked Henry about the genesis of his Mishima biography. “After his death,” he responded, “I immediately knew that I had to do something. I had original material, I knew a lot of details. I believed all of that was going to be lost unless I stirred myself. I used his materials so that he was, in a sense, speaking through that book.” On another occasion, I asked if he was able to reconstruct his movements and mental state on Mishima’s last day. He recalled, “Sitting in the taxi going over to Ichigaya, the scene of Yukio’s suicide, I was convinced he would commit seppuku (ritual disembowelment). I had this great desire that he should accomplish what he wanted. Some people might say that for a non-Japanese to have arrived at that stage of thinking, means that you have been in the country too long. But that is exactly where I stood on that day.”

The trauma of writing the Mishima book, of reliving the past, was replicated in a second work on the Kwangju massacre of May 1980, in which Korean paratroopers, trained to kill with their hands and clubs, went berserk amidst a protest by unarmed civilians. Visiting the site, Henry recalled, “There was a ghastly stench coming out of the city. For two or three years after Kwangju, I was completely in despair over the dark side of the human soul.” The publication in 2000 of The Kwangju Uprising, which Stokes co-edited with Lee Jai Eui, comprised the first anthology of eyewitness accounts by Western and Korean journalists of those ten days of horror.

Over the following years, Henry’s career underwent an interesting sea change, as he shifted his focus towards the arts, working closely with friends Christo and partner Jeanne-Claude. The Japan-U.S.A. Umbrellas project, was, arguably, Christo’s most ambitious installation to date. The potential intrusiveness and upheaval of bolting a total of 1,340 earth anchors, steel base frames, alumium super-structures, and the blue fabric that formed the domes of the umbrellas onto a rural landscape, must have seemed formidable. As Project Manager, this was where Henry came in. With his background in financial journalism and administration, and his involvement in the arts, it is difficult to imagine anyone else capable of assuming this responsibility.

The physical construction and manipulation of the umbrellas alone, was a Promethean task involving helix anchors and bases being screwed into rice-fields, the manhandling and rectilation of space, steel plates weighing almost 3,000 kilograms being lowered into the middle of the Sato River by crane, crews and divers up to their waist in water, wizened maids in bonnets and smocks portering steel parts, or wincing poles onto substructures placed in valleys and on vegetable terraces. Completed in 1991, 1,340 blue umbrellas, each six meters tall with a diameter of 8.7 meters, were opened in Ibaraki Prefecture, simultaneously with a similar number of yellow umbrellas in the hills of Southern California.

I recall wandering one autumn morning through that curiously transformed space, created in paddies, across irrigation ditches, rivers, vegetable terraces and shallow valleys. There was something overwhelming about that long-dismantled landscape, which transcended the need to know what it all meant. Perhaps this is a characteristic of major art, that it forestalls the inane inquiry. “I couldn’t quite learn fast enough to keep up with Christo and Jeanne-Claude,” Henry confided, “but they restored my sanity. Korea threatened my sanity; the Christos brought me back into this world.”

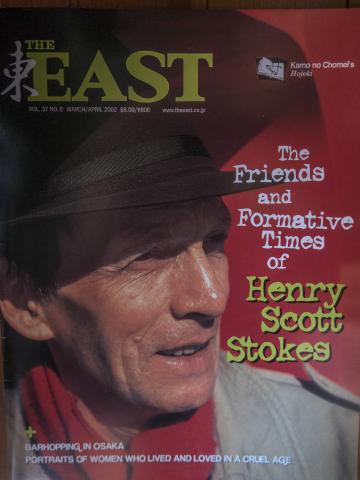

If Henry stood out from the crowd as a journalist, author, and project manager, the sartorial image he cultivated, formal, well-cut suits worn with a confident informality, also set him apart. In a forgivable affectation, winters were for beige trilbies and fedoras, summers for panama hats, his film noir period tastes closer to the debonair wardrobe of George Sander than the louche cool of a Robert Mitchum. He was also, as I recall, an avid self-publicist. When a long profile of him appeared in the spring issue of the magazine The East, back in 2002, it featured a front cover shot I had taken. The publication’s editor and owner were astonished when Henry stepped into their Tokyo offices and ordered 80 copies of the issue, to be distributed among friends and colleagues.

Until his luck ran out and he was felled by ill health, Henry was a man of boundless energy, intellectual curiosity, and cultural avidity. It only seems yesterday, as the old cliché goes, that my wife and I sat with him, drinking chilled white wine in the sunroom of our family house in Chiba, the conversation moving seamlessly from world events to literature, and finally, with the attention to detail of a musicologist, the discography of the Stones. Keith Richard’s mastery of open string tuning was lauded, Jagger’s sly lyrics admired, the band’s journey from the establishment-rattling bad boys of rock to beloved English institution, marveled at.

His favorite song, if I recall, was Sympathy for the Devil.

Stephen Mansfield is a Japan-based writer and photographer whose work has appeared in over 60 magazines, newspapers and journals worldwide. He is the author of 20 books. He is currently working on a new title for the British publisher Thames & Hudson.