Issue:

June 2022

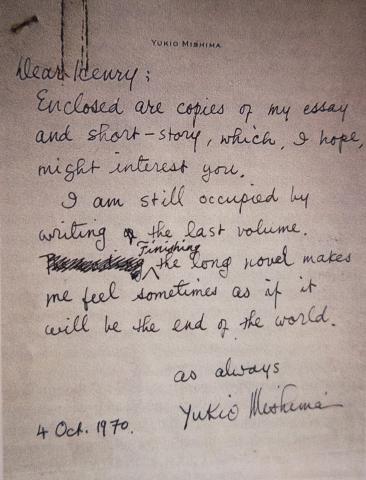

Remembering Henry Scott-Stokes

For a long time, I felt in Henry’s debt for opening doors needed for my first feature for the Observer Magazine.

The story was pegged to a Hollywood film about Yukio Mishima. In one of the most notorious incidents of Japan’s post-war era, the novelist committed ritual seppuku in1970 at the Ichigaya headquarters of the Self-Defense Forces, after failing to rouse the assembled soldiers to stage a coup d’état that would restore imperial rule. Henry had befriended Mishima and later written a book about him.

The director of the 1985 film, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, was Paul Schrader, the screenwriter of Taxi Driver that won Oscars for Robert DeNiro and Jodie Foster. Henry claimed the Mishima film infringed the copyright of his book and was engaged in a bitter dispute with Schrader. As a result of this tension, I only managed to speak with Schrader by telephone, at the eleventh hour before my deadline.

Henry had warned me of the difficulties of speaking to “the widow,” who had placed her late husband “on a pedestal” of artistic genius. Arranging the interview with Yoko Mishima involved tortuous negotiations through her lawyer and was conducted in his presence. Unable to banish from my mind a photograph of Mishima as Saint Sebastian impaled by arrows, I gingerly suggested that family life at times must have been difficult. “One more question like that and I shall leave the room,” she shot back.

Thanks to Henry’s introduction, I had lunch with Mishima’s younger brother Chiyuki at the Palace Hotel in Tokyo. Dressed in a dark three-piece pinstripe suit, plump, and with florid face and sideburns, Chiyuki easily could have passed for a bucho at an Otemachi office. A career diplomat at the Gaimuysho, what was most striking to me was his position at the time; on secondment to the Imperial Palace as a “vice grand master of the ceremonies”. Surely this signalled Hirohito’s recognition of his brother’s sacrifice for the imperial cause?

Mishima had created a private army called the Tatenokai or Shield Society, intended to protect the emperor from the forces of left-wing anarchy. Henry drew attention to the scandal of official encouragement they received: permission to train with the Ground Self-Defence Forces, and parade on the roof of the National Theatre. In far-flung Fukui Prefecture, I met a former Tatenokai member who had turned to making Japanese confectionery. His Tatenokai uniform, resembling that of a hotel bell hop, was proudly displayed.

As a condition for such access, I had promised that treatment by the Observer Magazine would be in “good taste”. My editor did not feel so bound, and over two pages splashed a grisly black-and-white photograph of the aftermath of seppuku at the army commandant’s office, with the severed heads of Mishima and his lieutenant Masakatsu Morita on the blood-drenched carpet.

Some obituaries of Henry refer to a lifelong attraction to right-wing causes. I was not conscious of any such leanings when Henry was still in his journalistic prime. He showed no sympathy for Asia’s right-wing military dictators, including Park Chun-hee of South Korea. Indeed, he edited a collection of essays entitled ‘The Kwangju Uprising: A Miracle of Asian Democracy as Seen by the Western and the Korean Press’ with a foreword by Kim Dae-jung!

Henry conformed to the image of an upper-class English gentleman. Educated at Winchester and New College, Oxford, with a double-barrelled surname, a languid air, and a professional pedigree of prestigious employers, he seemed to live at a higher altitude than most denizens of the FCCJ. However, he was not born in some mouldering aristocratic pile. His bourgeois origins, which he never shared with me, were in fact far more interesting. The family fortune came from manufacturing sheepskin rugs, coats, and footwear, all once considered fashionable. ‘Morlands of Glastonbury’ gave Henry one of his middle names (Henry Johnstone Morland Scott-Stokes). His mother was the daughter of Morland’s Quaker founder, and a pacifist. Henry’s father, also educated at Winchester and New College, was mayor of Glastonbury six times and twice stood for Parliament as a Liberal candidate. In 1928 he co-authored a paper entitled The Security of the Worker: What Some Employers Think and in the 1950s turned down the offer of an award from the monarch.

Hardly the typical breeding ground for an apologist of Japanese militarism ….

Peter McGill was North-East Asia correspondent of The Observer and was based as a journalist in Japan for 19 years. He was president of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan from 1990 to 1991. He was first employed as a civil servant in Hong Kong. In recent years he has written mainly for financial magazines.