Issue:

December 2021

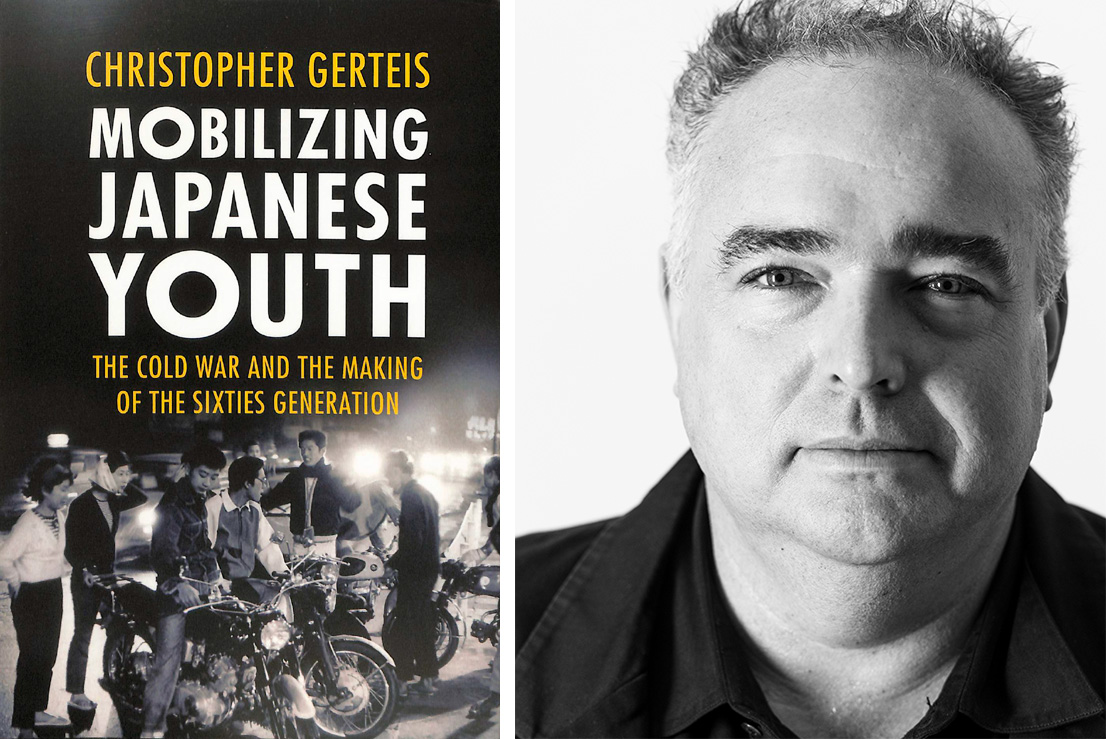

An extract from, Mobilizing Japanese Youth: The Cold War and the Making of the Sixties Generation

The Japanese Red Army [JRA] attracted only a few dozen members-under-arms, but its brief international moment between 1971 and 1976 had a significant impact on the cultural space of youth radicalism, evident in the launching of the punk rock movement in Japan. In March 1972, Victor Records released the first commercial album by the protopunk band Zunō Keisatsu (the Brain Police), which, for many of its songs, took inspiration from Red Army political rhetoric and its iconography of masculinist violence.1 Founded in 1969 by “garage rock” musicians Nakamura Haruo, Ishizuka Toshiaki, and Kikuchi Takumi, partly as an homage to the music pioneer Frank Zappa, Zunō Keisatsu’s performances were ubiquitous at RAF political meetings and associated political protests. Indeed, Nakamura later explained that his lifelong fascination with Shigenobu inspired much of his work as a lyricist and musician.

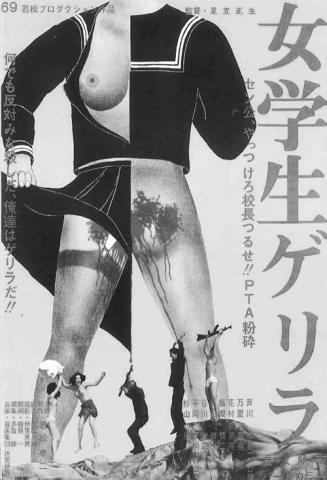

Formed amid the political turmoil of 1969, Zunō Keisatsu often performed at small club venues, political rallies, and major demonstrations in the Tokyo area. The group debuted at the Kanda Kyoritsu Auditorium in April 1970, where Nakamura’s confrontational lyrics and wild, angry, and frenetic performance—which included dropping his trousers onstage—were widely criticized by the mainstream media, and their performances were often disrupted by police for violating public morality laws. The garage rock subculture out of which the punk movement emerged was far from uniform, but the punk genre was generally understood as a vocal lead engaged in loud, aggressive slogans, choruses, and terrace chants while accompanied by one or two guitarists, a bassist, and a drummer. Punk arrangements were generally short and laden with ideological lyrics. While histories of punk identify the first semicommercial punk labels as emerging in New York during the mid-1970s, Zunō Keisatsu signed with the very commercial Victor Records late in 1971; their first album was a compilation of live performances recorded in Kyoto in January 1972 and was released in March of that year. Despite its capitalist origins, the albumborrowed heavily from the JRA’s political vision to articulate an antiauthoritarian, heterodoxic cultural practice that coemerged alongside, yet was distinct from, the New York Dolls (1971) and the Clash (1976).

Victor Records caved to informal police pressure and voluntarily withdrew the album from publication after just three weeks, part of the record industry’s “voluntary censorship” of materials that the state authorities declared to be at odds with the public-welfare laws that also governed pornography and the sex trade. The album was indeed meant to be very provocative, and its release coincidently overlapped with Shigenobu’s communiques from Lebanon imploring the youth of Japan to come join the PFLP’s global fight for liberation. 2 The album’s first track, “Introduction: Declaration of World Revolutionary War,” featured lead vocalist Nakamura’s reworked version of the RAF’s September 1969 manifesto. Nakamura later explained that he sought to use his lyrics to explore the duality of coming of age in Tokyo during the late 1960s: the city resonated with the anger felt by youth who saw their mass mobilizations for social and political change crushed under the weight of police suppression and widespread apathy.Nakamura gave voice to a shared fury over the United States’ continued oppression of the Vietnamese people, the war against the Black Panther Party, and support for the Park dictatorship in South Korea.

The recording begins with a string of firecrackers, which mimics the sound of gunfire, after which Nakamura rapidly screams his rage against the system: “Bourgeoisie Ladies and Gentlemen! We openly declare war on ourselves in order to purge and drown you in the World Revolutionary War.” He continues:

If you have the right to kill our Vietnamese friends, we also have the right to kill you.

If you have the right to murder our Black Panther comrades and crush the ghetto under tanks, we also will kill Nixon, Sato, Kissinger, de Gaulle, bomb the Pentagon, the Defense Agency, the Metropolitan Police Department, your houses.

If you have the right to bayonet our Okinawan comrades, we also have the right to stab you with bayonets.

If you have the right to build the Self-Defense Force in support of another war in Korea, arrest those who oppose it, and support the Park dictatorship, we too have the right to build the Red Army, make a declaration of revolution, arrest and condemn you to death.

We fought against the [feudal] lords under the slogan of “freedom, equality, bravery” to break this framework and make ourselves free.

But now we declare openly and decisively that we will not do your bidding.

Your time is over.

We will fight to the very end in order to kill you from this world in the name of the last war, the class war, to eliminate you from the earth,

In the name of victory for the World Revolutionary War, we openly gun for the Self-Defense Forces, the Riot Police, and the US military.

If you do not want to be killed, turn the gun around! Toward yourself and toward the bourgeoisie behind you.

Anyone who will interfere with the project of liberating the world proletariat will inevitably be killed in the midst of the World Revolutionary War.

Unchain the proletariat of the world!

Our Declaration of the World Revolutionary War begins here. 3

Overtly and loudly political, Nakamura’s lyrics railed against the Japanese state’s total capitulation to the whims of US imperialism. Like many musicians associated with the punk genre, Nakamura lay bare issues central to the global antiestablishment, countercultural youth movements of the Cold War era. Historians of the punk rock groups that emerged in London and New York during the mid-1970s establish that groups like the Clash, Screwdriver, and the New York Dolls were the vanguard of the working-class angst that arose from deindustrialization. Early punk ideologies spanned from the Far Right (Screwdriver) to the Far Left (the Clash), but they shared a common frustration with a political establishment that had failed to challenge the severe economic inequalities faced by urban working-class youth.

Zunō Keisatsu’s sound and lyrics grew alongside an audience composed of the radical youth of the late 1960s, whose actions also helped to shape the music. Fanzines celebrated Nakamura’s “Declaration of World Revolutionary War” as the first in a revolutionary trilogy—the first three tracks on the group’s 1972 album—that was emblematic of the political rage felt by a generation of youth whom the state had blocked from exercising their demographic’s political majority. The second track, “Sekigun heishi no uta”(Song of a Red Army soldier), incorporates the work of the German poet Bertolt Brecht into a dark criticism of contemporary Japan’s role in “devouring the earth,” while the third track, “Jū o tore” (Pick up a gun!), ends somewhat predictably by calling on the audience to “pick up a gun, pick up a gun, pick up a gun.” 4 While Nakamura explained to contemporaries—and the media—that his music was foremost an exploration of how to expand the expressive limits of the Japanese language, it is nonetheless significant that he made artistic use of Red Army ideology—and its masculinist lexicon for political violence—to express himself. His combination of vulgarity, fury, and political critique resonated with the historical moment: “Declaration of World Revolutionary War” and its accompanying tracks position the audience, and band, within the revolutionary rhetoric that Shigenobu Fusako sought to shape in her effort to persuade recruits to join the JRA.

Five weeks after Victor Records withdrew Zunō Keisatsu’s album, Shigenobu’s twenty-seven-year-old “paper husband,” Okudaira Tsuyoshi, twenty-five-year-old Yasuda Yasuyuki, and Okamoto Kōzō, the twenty-five-year-old younger brother of the Yodogō hijacker Okamoto Takeshi, traveled via Rome to Lod Airport in Tel Aviv, where, on May 30, 1972, they launched what Shigenobu would be forced to rebrand as the first joint offensive by the PFLP and the JRA. The tie-up was the logical consequence of Shigenobu’s epic transformation from a pink-collar worker into an international revolutionary, which was bolstered by her masterful orchestration of recruitment propaganda. Perhaps more significantly, the Lod Airport attack was the first in a series of hostage takings, hijackings, and mass shootings that helped shape the international media’s presentation of the early 1970s as the start of an age of global terrorism.

Christopher Gerteis is Associate Professor of Contemporary Japanese History at SOAS University of London and Associate Professor and Academic Editor at the University of Tokyo's Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia. He is also the author of Gender Struggles.

- Lead singer, lyricist, and group founder Nakamura Haruo explained that the band name was an homage to the A-side track on Frank Zappa’s 1966 single for Verve Records, “Who Are the Brain Police?”

- Jon Savage, England’s Dreaming: The Sex Pistols and Punk Rock (London: Faber and Faber, 1991), 3-10.

- Nakamura Haruo, “Intorodakushon: Sekai kakumei sensō sengen,” Zunō Keisatsu 1 (reissued by Hyabusa Landings/Flying Publishers, 2012).

- Nakamura “Intorodakushon.”