Issue:

December 2023

Shifting sands of history are influencing Japanese media coverage of the Hamas-Israel war

After a car ran through the police barricade outside the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo on Thursday, November 16, online reaction to the incident mirrored the reaction to viral videos of an October 11 gathering of Israel supporters in front of crowded Shibuya Station. This level of interest in the Middle East - in Japan?

Global perception of both events speaks to how many people might assume Japan and Israel have no particular connection. But if we look at the domestic reaction to these events and the conflict between Israel and Hamas, we find that Japanese perceptions of Israel are neither singular nor sudden.

Rather, domestic Japanese politics have shaped how the media represent Israel in Japan.

For instance, when the car rammed into the barricade, police were quoted in Japanese media saying the suspect was part of an ultranationalist, far-right group – something that surprised Japanese posters on X (formerly known as Twitter). Many commenters wrote that they would have expected such an act from someone on the far left. Conversely, in response to news articles about the rally at Shibuya Station, Japanese netizens speculated that compatriots who had taken part in the march must be right-wing Christians.

What has led to a situation in which online commenters assume certain groups in Japan are supportive of Israel, and why do they assume other groups are opposed not just to Israel’s war against Hamas, but to the state of Israel more generally? And what does all this portend for how the events in Israel and Gaza are impacting Japanese politics?

To understand how perceptions of Israel have evolved in Japan, we can take a look at three key flashpoints: the trial of Adolf Eichmann; the Oil Crisis of 1973; and late former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s attempts at rapprochement in bilateral Israeli-Japanese ties.

For many in Japan, Eichmann’s trial was the first, if not most significant, account of the Holocaust they had encountered – and their first exposure to the young state of Israel. Japan established full diplomatic relations with Israel as soon as the Occupation ended in 1952, but the normalization of diplomatic ties led to little consciousness about Israel in Japan. During the trial, papers and televisions provided a glimpse into the horrors of the Holocaust through the trial of one of its perpetrators. Indexing how important this event was for Japanese public opinion, just this year, writer Masahiro Yamazaki published Eichmann and the Japanese People. During the trial, even writers criticizing Israel’s capture of Eichmann in Argentina, or the specifics of the trial, wrote of the Holocaust as a uniquely horrendous event in human history.

This period even saw some leading intellectuals in Japan turn toward Israel, and even more generally, Jewish people. Intellectuals such as novelist Kōbō Abe and anthropologist Masao Yamaguchi wrote about the importance of Jewish contributions to global culture, and what they perceived as their own affinities, as Japanese, with Jews.

Only a few years after the Eichmann trial, the Six-Day War (1967) again turned Japanese attention toward Israel. While figures on the left decried what they argued was Israeli colonialism and imperialism, many reports of the war in Japan expressed palpable surprise at, and mild admiration for, Israeli military exploits. But just half a decade later, this war and its consequences led into the second flashpoint for understanding the way history has shaped present ideas of Israel in Japan: the Oil Crisis of 1973.

Following 1973’s Yom Kippur War (also known as the Fourth Arab-Israeli War), the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) slapped an oil embargo on countries that had supported Israel. The war began when an Egyptian and Syria-led coalition launched a surprise attack on Israel during Judaism’s holiest day, Yom Kippur (sometimes known in English as “The Day of Atonement”).

While the coalition led by Egypt and Syria made initial gains, Israel’s counterattack succeeded in threatening both the Syrian capital of Damascus and the Egyptian capital of Cairo. In part, war had broken out as a means to try and force a return to pre-1967 (before the Six-Day War) borders by gaining land, and then forcing Israel to negotiate. The oil embargo, begun after the tide of war had turned in Israel’s favor, was a stated means to push Israel to return not to the pre-1967 boundaries but to the borders as they were after the 1949 Armistice Agreements, which ended the First Arab-Israeli War.

The embargo had far-reaching effects, and set off a global recession. Japan’s stockpiled oil reserves were hardly enough to insulate its economy and people from hardship. Not only had OAPEC embargoed countries that supported Israel, they also slashed oil production. Resource-poor Japan forced the government to seek solutions often at odds with U.S. foreign policy, and in particular, its stance on the Middle East.

Little over a month after the oil embargo began, on November 22, 1973, Chief Cabinet Secretary Susumu Nikaidō issued a statement that called for a return to the pre-1967 borders of Israel. Perhaps the most significant manifestation of an independent Japanese Middle East policy came in 1975, when Japan abstained at a United Nations General Assembly vote for adopting a resolution that Zionism is a form of racism, rather than voting with the U.S.

But, as Israeli protestors’ vociferous critiques of Benjamin Netanyahu’s government – both before and since Israel’s campaign in Gaza – show, there is hardly a one-to-one reflection of a government’s policies in its citizens’ views. So, what caused Japanese coverage of Israel to abandon its largely pro-Israel slant?

Major Japanese corporations had covertly or overtly abided by the Arab League’s boycott of Israel well into the 1990s. Today, this boycott is largely irrelevant owing to various peace treaties signed between Arab League members and Israel. But some leading Japanese companies such as Toshiba, Nippon Steel, and Hitachi would not trade with Israel into the 1990s. In their 1995 book, Jews in the Japanese Mind, scholars David Goodman and Masanori Miyazawa underscore the impact of the Oil Crisis by pointing to a write-up about the impending first visit of a Japanese government minister in Japan, with the Economist offering: “Talk of trading with Israel is taboo in Japan. South Africa is considered far more respectable.”

Furthermore, the bubble economy of 1986-1991 brought along an unprecedented rise in antisemitic publications in Japan that further maligned both Israel and Jews as a group. As Haifa University Professor Rotem Kowner wrote in a 1997 article: “By 1987 nearly a hundred books which carried the word ‘Jew’ in their titles were in circulation and many large bookstores displayed them in a special ‘Jewish’ corner.”

In short, chilly bilateral ties came to exist alongside increasingly negative perceptions of Israelis and Jews. But as online commenters’ recent vitriolic online reaction to some Japanese Christians’ show of support for Israel suggests, Japan’s right is today associated not with distance from Israel, but closeness.

This brings up a third flashpoint for understanding today’s coverage of Israel in Japan, which occurred during Abe’s two tenures as prime minister. Abe facilitated a warming of ties with Israel based on shared economic and military agendas. There are numerous reasons for those closer ties. In part, Japan’s competitors in technology abroad had gained increasing access to Israel’s high-tech economy during chilled relations. Key, though, was how Abe sought new global partners to strengthen Japan’s defensive posture. Especially after the Arab Spring in 2011, Israel appeared a stable ally aligned with Japan’s interests, and an untapped market.

Yet opposition parties and critics of Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) have disparaged increasingly close ties between Israel and Japan as not representing Japan’s interests or voters’ values. Now, opposition parties are using the LDP’s ongoing support of Israel as a means to lambast the increasingly unpopular administration of Fumio Kishida. Japanese surveys have already shown that Kishida’s cabinet has passed the point of no return, dropping below 30% approval rating – a line that has historically ushered in a new prime minister. War is arguably even more unpopular than the current government, though – renounced not just by Article 9 of the postwar Japanese constitution, but arguably a majoritarian Japanese ethos as well.

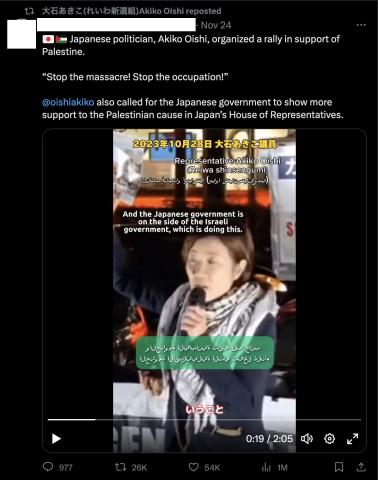

Japanese opposition parties have historically opposed foreign wars, and the current conflict in Israel is no exception. Parties ranging from the upstart Reiwa Shinsengumi and Social Democratic Party, to opposition stalwarts such as the Communist Party of Japan, have come out clearly against Israel’s military response since October 7. Opposition to Israel’s military response, then, reflects both the long-held values of specific parties in Japan, as well as to use specific policies and positions of the current administration to press for electoral change.

Akin to how Japanese stances towards Israel and Palestine are shaped by domestic politics, Japanese reporting on the news from Israel and Gaza reflects diverse positions shaped by factors beyond the events since October 7. Like other countries, the way the current conflict is being reported in Japan changes depending on the TV network or newspaper. Papers and publications on the right of the political spectrum, such as the Sankei Shimbun and the monthly opinion magazine WiLL, have published articles decrying the October 7 massacre as terrorism, and continue to support the Israeli military response.

While we might be able to associate the respective stances toward Israel’s military response to October 7 with the left and right of Japan’s political spectrum, what are we to make of comments like those on MBS’s Kyō no Genba on October 19, or TBS’s Sunday Morning on November 19: that Jews control the media in many Western countries and use the media to influence support for Israel? For instance, the former television program featured a guest who claimed “Jewish capital (yudaya shihon)” plays a key role in American electoral politics:

“America is a large place, and it's impossible to travel everywhere, so elections are largely television elections," the guest said. "Television elections are, more than anything, buying TV time. And it costs a massive amount of money, and this is where Jewish capital has tremendous power …. Since people in Israel and Jewish capitalists in the U.S. have a close relationship, if a political candidate says, ‘I don't support Israel,’ they will turn against you immediately.”

Disparagement of Israel through antisemitic tropes is hardly unprecedented, as a review of the bubble economy years shows. Antisemitism’s recurrence in contemporary criticism of Israel, from both left and right, serves only to signal that such perspectives tell us nothing about the facts of the conflict. Instead, these prejudiced and uninformed perspectives speak to how the conflict has become fodder for domestic politics.

At this crucial juncture, the media have an important role to play globally in documenting what is taking place in Israel and Gaza, as well as providing the experiences and perspectives of those impacted by the conflict. It is worth noting, then, that as I continue to have conversations with Jewish groups in Japan that assist with my ethnographic fieldwork, they feel their own perspective is not represented in the media. For instance, some have tried, to no avail, to reach out and provide interviews with media outlets that have made concerning statements about the Holocaust since October 7. And they aren’t alone: exploring social media, I have found multiple firsthand accounts of Palestinians living in Japan who have wanted to talk to the Japanese media – some were even invited to talk – only to be told that their story was not what the media were looking for.

This all signals that rather than an organic relay of events in Israel and Gaza, there is an important framing of events by at least some media outlets, in two important ways.

First, whether it is Japan abstaining from an October 28 vote at the UN on a ceasefire, or Japan’s continued relations with Iran due to its need for imported oil (Kishida met with the Iranian president in September), Japanese diplomacy and politics regarding Israel and Gaza – as well as organized opposition to them – are shaped by much more than the events since October 7. When reporting situates the ruling coalition and opposition parties’ current positions as emerging from the massacre in Israel or Israel’s campaign in Gaza, there is a risk of erasing a wider geopolitical context and longer history that shapes the ruling coalition and opposition’s positions.

Second, today’s coverage in Japan is not taking place in a vacuum. Nor is it objectively relaying what is happening in Israel and Gaza. Different news outlets’ framing of the conflict have been nurtured by roots that go much deeper than the events since October 7. By not acknowledging these roots, the media play a role in making specific perspectives about Israelis and Palestinians appear as natural. In reality, the Japanese media’s framing of events since the Hamas massacre in southern Israel is inseparable from how Japanese politics and post-war history shape both the government and political parties’ stances toward Israel.

The media have an obligation to point out and clarify for their audiences the motivations behind different domestic groups’ stances on this conflict, and to help them understand what perspectives are missing from that coverage. They must also seek to explain the historical factors behind the divergent ways in which the conflict is being covered, and how that has also been influenced by Japan’s domestic political agenda.

Dylan O’Brien is a PhD Candidate in Cultural Anthropology at the University of California, San Diego. His research examines how representations of Jews and Judaism in Japan interact with Jews living in Japan.