Issue:

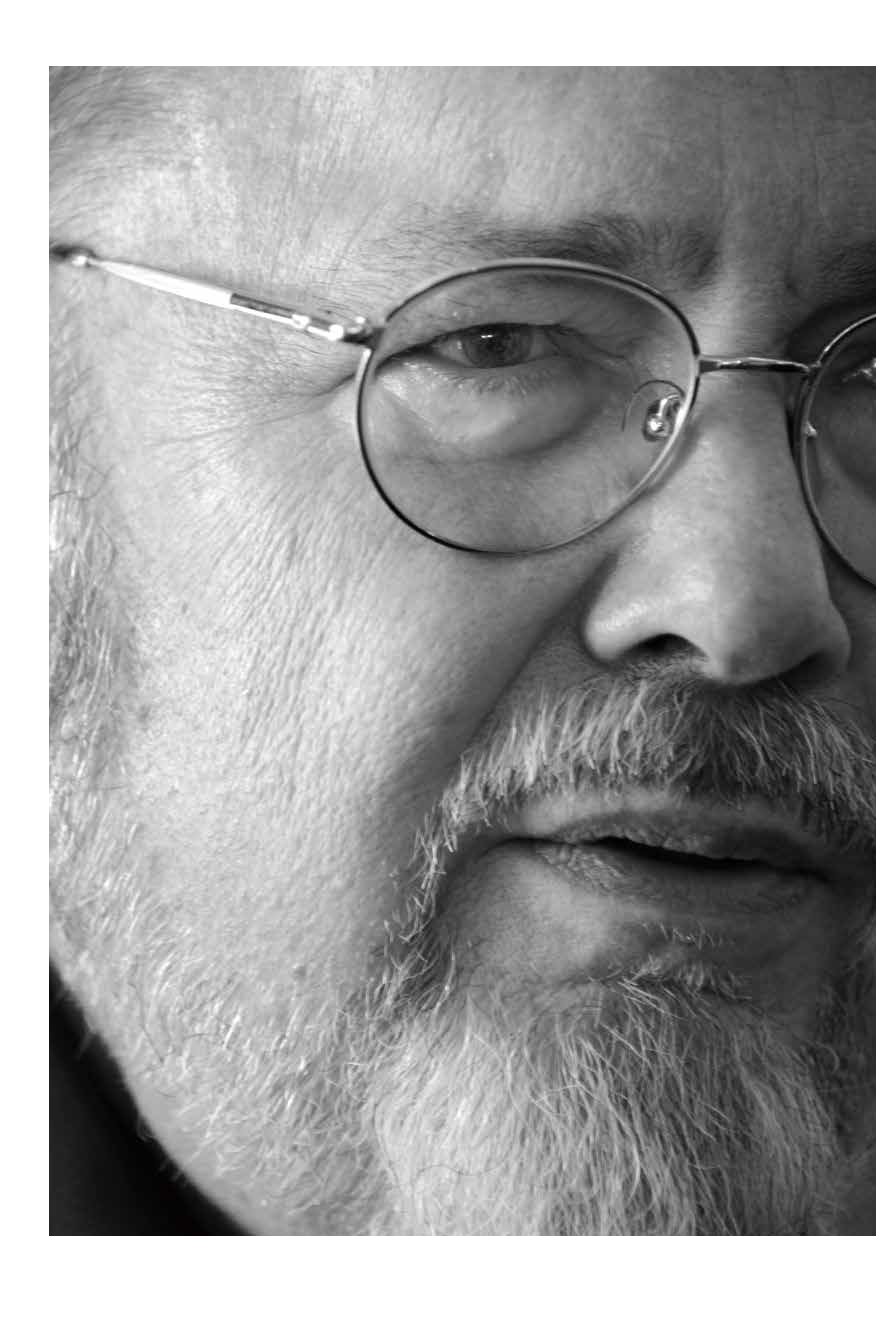

Bradley Martin credits the burning desire to get as far away as possible from Marietta, Georgia to thank for datelines as coveted in the news business as Kabul and Pyongyang, as well as countless other corners of Asia over the course of a five-decade career.

Now 74, he gets back to Marietta occasionally to see family and friends, but shakes his head wryly when he admits, “I don’t know more than four people there who did not vote for Trump.” His first escape from Georgia was to Princeton University, where he studied U.S. and Asian history. “We had always had trinkets around the house from my uncles’ duties in the Philippines and other parts of East Asia Chinese gadgets and souvenirs, a Buddha statue and I just became interested in the region without knowing very much about it,” he says.

Graduating in 1964 and starting law school, Martin had no ambitions of a media career, but was a voracious consumer of the news provided by Newsweek. The headlines were dominated by the “wonderful war that was going on in Southeast Asia at the time,” Martin recalls, and he even seriously considered joining the military to take part in “my generation’s war.”

Instead, his wife at the time convinced him that they should both join the Peace Corps, and they swiftly found themselves teachers in Bangkok. “It took me three weeks to figure out that what was going on over the border was a stupid war that we could not win, and I was extremely angry at how I had been misled,” Martin says. “I told myself I could do better and that if I became a foreign correspondent, I would do better.”

Lacking the required experience and clips the Thailand director of the Peace Corps was an old news-paper hand and had to explain what clips were Martin launched a quar-terly journal for the organization and, after returning to the U.S., was able to parlay his experience into a position on the Charlotte Observer. Cutting his teeth on poverty, race relations and urban affairs, he later moved to the Baltimore Sun because it employed foreign correspondents. After three years as a business reporter, he was sent to Tokyo in 1977.

“From the very beginning, I loved the place,” he says. “In those days, the Club was quite lively. There were fist fights in here and I was in at least one of them myself. You could say we were quite a rowdy bunch.”

It was also a good time to be a correspondent, though Kakuei Tanaka and the Lockheed scandal were receding into history. “Japan was interesting politically, but there was no bang-bang, ” says Martin. “That was going on in South Korea with the demonstrations against Park Chung-hee.”

“I told myself I could do better and that if I became a foreign correspondent, I would do better.”

Then came October 1979. “It happened to be my birthday, there had been a party and we had all had rather a lot to drink,” Martin says. “In the middle of the night, my editor rang and I thought he said that a big yakuza had been killed, that I needed to get down to the Reuters office to file and then get the first plane to Seoul in the morning.” The information seemed confused and contradictory, but Martin checked with his police contacts about yakuza killings before learning that Park Chung-hee had been assassinated by his own secret service chief.

Over the next few years, he spent much of his time in Seoul, interspersed with spells in New Delhi and Beijing, and kept a close eye on events in Korea even after switching to the Asian Wall Street Journal. He crossed the Khyber Pass into Afghanistan aboard a public bus soon after the Soviet invasion in 1979 and recalls watching battles taking place around his hotel in Kabul. He was in Gwangju, South Korea, in 1980 in the latter stages of the uprising, before it was put down.

But everyone who covered Asia wanted to get into North Korea. “It was forbidden,” he says. “Eventually, I managed to get accredited to cover the 1979 World Table Tennis Championships.” He did not take in many table tennis matches, instead using the time to meet as many government officials as possible and to travel as much of the country as his minders would permit. An interview with Kim Yong-nam, now the president of the Supreme People’s Assembly, lasted five hours.

Martin’s reports were so successful that he was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. They also served as the basis for his critically acclaimed book, Under the Loving Care of the Fatherly Leader: North Korea and the Kim Dynasty. “It was a fascinating place that was just so different from anything else,” he says. “It was a religious kingdom where the people worshiped Kim Il-sung and I just soaked it all up.”

Martin has visited North Korean on seven occasions, including while he was writing for Bloomberg, but does not expect to be permitted to return again. An application last year to study Korean in Pyongyang was summarily turned down.

Given that Under the Loving Care is now 13 years old, Martin who divides his time between homes in Hawaii and Nagano Prefecture says he is toying with the idea of writing a follow-up, although his recent efforts have been focused on his first novel, Nuclear Blues, expected to be published in the next couple of months.

Julian Ryall is Japan correspondent for the Daily Telegraph.