Issue:

Dr. Eugene Aksenoff led a remarkable life of assistance to the down-and-out and the glitterati alike. Upon his passing, everyone has a story

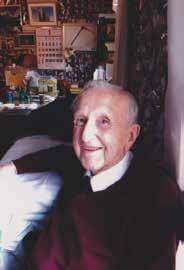

COURTESY INTERNATIONAL CLINIC

Ithought it wise to get some vaccinations before my first trip to rural Thailand. I’d heard the place for that in Tokyo was the International Clinic in Roppongi, and was amazed to find it in a prewar house squeezed into a cramped corner lot shaded by persimmon, fig and avocado trees. Inside the house was a smiling man who seemed to come from another world.

Dr. Eugene Aksenoff sat at his large wooden desk in front of walls covered with hundreds of photos of smiling children, his young patients from Japan and overseas. I was astounded when he told me he’d come to Japan before the end of World War II, before Donald Richie and every other old timer gaijin I’d met.

So it is understandable that Aksenoff’s passing on Aug. 5 at age 90 came as a shock to the foreign community in Tokyo. Having been in Japan for over 70 years, he was like a beacon for residents and visitors alike.

“He was the sort who made you feel better the moment you entered the office,” says Kyodo News editor Darryl Gibson, who was once treated by the doctor for an infected wound from diving. “Even if he did nothing other than listen to you describe an ailment and tell you not to worry, you immediately felt better.”

“He was one of the nicest men you could ever meet,” agrees Bill Hersey, longtime social columnist for Tokyo Weekender magazine. “He used to take care of all kinds of people who didn’t have any money young fashion models who came here and got sick, laborers, anybody.”

The unheralded, day-to-day care of people at the International Clinic didn’t make Aksenoff famous it was his status as doctor to the stars. Among the photos tacked to the walls of his office is a snap shot with Michael Jackson, one of many celebrities who benefitted from Aksenoff’s hotel house calls over the years.

“His priority was kids, very old people, and very sick people. But for most of the hotels in Tokyo, he was the doctor,” says Rumi Yamamoto, a nurse who worked with Aksenoff for 21 years, and helped him treat such VIPs and their families as Steven Seagal, Stevie Wonder, Rhianna, Oasis, KISS and jazzmen from Blue Note Tokyo. Frank Sinatra, John Wayne, Madonna, Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie and Lady Gaga were also Aksenoff patients.

The doctor would answer urgent calls from hotels at all hours of the night, Yamamoto recalls. He was so dedicated to his work that when he was discharged from the hospital for his own ailments in his later years, he would immediately return to his clinic. In the end, in fact, his staff were lifting him up the front steps in his wheelchair.

As Yamamoto sits at Aksenoff’s desk beside a shelf full of books in English, Japanese, German and Russian, she pulls out more mementos: a letter of thanks from Jacques Chirac when he was mayor of Paris, a copy of Aksenoff’s Japanese medical license from 1951, and a young Aksenoff in a cadetstyle school uniform in the 1940s.

The way Aksenoff would tell the story, his parents were White Russians who had fled Russia to Harbin, China where Aksenoff was born in 1924. When he was about five years old, a European doctor treated him for a cold. He was so deeply impressed by the man’s kindly manner and the cleanliness of the hospital that he resolved to become a doctor himself one day.

After Japan seized Manchuria and created the puppet state of Manchukuo in 1932, Aksenoff’s father made some Japanese acquaintances through raising horses. One of them was Count Yoshitaka Tsugaru, a Japanese noble who invited Aksenoff fils to Japan to study medicine.

Aksenoff found himself one of the few Caucasians in Tokyo during the war, which he spent studying Japanese at Waseda University and medicine at Jikei University. He paid for his tuition by playing captured American pilots in propaganda films. After the war ended, he worked with the U.S. military as a translator, did a stint at Seibo Hospital and helped establish the Tokyo Medical and Surgical Clinic before opening his International Clinic in 1953.

Though Aksenoff was actually a stateless person who never took Japanese citizenship, the Russians who filled his practice during the Cold War drew the attention of U.S. and Japanese authorities and he was soon suspected of being a Soviet spy. According to author Robert Whiting, Japanese intelligence agents arrested him for espionage because he’d been seen with a transmitter bearing markings that resembled Cyrillic. But he was released a week later when a Toshiba engineer explained that the symbols were Toshiba’s markings for digital equipment and the transmitter wasn’t a Soviet radio at all. Aksenoff took it all in stride.

“He was a generous person,” says Whiting. “He and Nick Zappetti, who ran Nicola’s pizzeria nearby, had a deal where by if a patient was down and out and couldn’t pay, Aksenoff would treat him for free and send him down to Nicola’s for a free meal.”

There seem to have been as many tales surrounding Aksenoff as his patients. One thing that friends agree on is the doctor’s golden character.

“He was so kind to everyone he met. Everyone came to him because they wanted to see him and hear his stories,” says Dr. Grant Mikasa of the American Clinic Tokyo, a former colleague. “That’s why he lived so long.”

Tim Hornyak is Tokyo correspondent for IDG News Service.